Algorithmic Differentiation

In science and engineering it is often necessary to study the relationship between two or more quantities, where changing of one quantity leads to changes of others. For example, in describing the motion an object, we denote velocity \(v\) of an object with the change of the distance regarding time:

\[v = \lim_{\Delta~t}\frac{\Delta~s}{\Delta~t} = \frac{ds}{dt}.\]This relationship \(\frac{ds}{dt}\) is called “derivative of \(s\) with respect to \(t\)”. This process can be extended to higher dimensional space. For example, think about a solid block of material, placed in a cartesian axis system. You heat it at some part of it and cool it down at some other place, and you can imagine that the temperature \(T\) at different position of this block: \(T(x, y, z)\). In this field, we can describe this change with partial derivatives along each axis:

\[\nabla~T = (\frac{\partial~T}{\partial~x}, \frac{\partial~T}{\partial~y}, \frac{\partial~T}{\partial~z}).\]Here, we call the vector \(\nabla~T\) gradient of \(T\). The procedure to calculating derivatives and gradients is referred to as differentiation.

Differentiation is crucial to many scientific related fields: find maximum or minimum values using gradient descent; ODE; Non-linear optimisation such as KKT optimality conditions is still a prime application. One new crucial application is in machine learning. The training of a supervised machine learning model often requires the forward propagation and back propagation phases, where the back propagation can be seen as the derivative of the whole model as a large function. We will talk about these applications in the next chapters.

Differentiation often requires complex computation, and in these applications we surely need to rely on some computing framework to support it. Differentiation module is built into the core of Owl. In this chapter, starting from the basic computation rule in performing differentiation, we will introduce how Owl supports this important feature step by step.

Chain Rule

Before diving into how to do differentiation on computers, let’s recall how to do it with a pencil and paper from our Calculus 101. One of the most important rules in performing differentiation is the chain rule. In calculus, the chain rule is a formula to compute the derivative of a composite function. Suppose we have two functions \(f\) and \(g\), then the chain rule states that:

\[F'(x)=f'(g(x))g'(x).\]This seemingly simple rule is one of the most fundamental rules in calculating derivatives. For example, let \(y = x^a\), where \(a\) is a real number, and then we can get \(y'\) using the chain rule. Specifically, let \(y=e^{\ln~x^a} = e^{a~\ln~x}\), and then we can set \(u= a\ln{x}\) so that now \(y=e^u\). By applying the chain rule, we have:

\[y' = \frac{dy}{du}~\frac{du}{dx} = e^u~a~\frac{1}{x} = ax^{a-1}.\]Besides the chain rule, it’s helpful to remember some basic differentiation equations. Here \(x\) is variable and both \(u\) and \(v\) are functions with regard to \(x\). \(C\) is constant. These equations are the building blocks of differentiating more complicated ones. Of course, this very short list is incomplete. Please refer to the calculus textbooks for more information. Armed with the chain rule and these basic equations, wen can begin to solve more differentiation problems than you can imagine.

| Function | Derivatives |

|---|---|

| \((u(x) + v(x))'\) | \(u'(x) + v'(x)\) |

| \((C\times~u(x))'\) | \(C\times~u'(x)\) |

| \((u(x)v(x))'\) | \(u'(x)v(x) + u(x)v'(x)\) |

| \((\frac{u(x)}{v(x)})'\) | \(\frac{u'(x)v(x) - u(x)v'(x)}{v^2(x)}\) |

| \(\sin(x)\) | \(\cos(x)\) |

| \(e^x\) | \(e^x\) |

| \(log_a(x)\) | \(\frac{1}{x~\textrm{ln}~a}\) |

Differentiation Methods

As the models and algorithms become increasingly complex, sometimes the function being implicit, it is impractical to perform manual differentiation. Therefore, we turn to computer-based automated computation methods. There are three different ways widely used to automate differentiation: numerical differentiation, symbolic differentiation, and algorithmic differentiation.

Numerical Differentiation

The numerical differentiation comes from the definition of derivative. It uses a small step \(\delta\) to approximate the limit in the definition:

\[f'(x) = \lim_{\delta~\to~0}\frac{f(x+\delta) - f(x)}{\delta}.\]This method is pretty easy to follow: evaluate the given \(f\) at point \(x\), and then choose a suitable small amount \(\delta\), add it to the original \(x\) and then re-evaluate the function. Then the derivative can be calculated. As long as you knows how to evaluate function \(f\), this method can be applied. The function \(f\) per se can be treated a black box. The implementation is also straightforward. However, the problem with this method is prone to truncation errors and round-off errors.

The truncation error comes from the fact that the equation is only an approximation of the true gradient value. We can see their difference with Taylor expansion:

\[f(x+h) = f(x) + hf'(x) + \frac{h^2}{2}f^{''}(\sigma_h)\]Here \(h\) is the step size and \(\sigma_h\) is in the range of \([x, x+h]\). This can be transformed into:

\[\frac{h^2}{2}f^{''}(\sigma_h)= f'(x) - \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}.\]This represent the truncation error in the approximation. For example, for function \(f(x) = sin(x)\), \(f''(x) = -sin(x)\). Suppose we want to calculate the derivative at \(x=1\) numerically using a step size of 0.01, then the truncation error should be in the range \(\frac{0.01^2}{2}[sin(1), sin(1.01)]\).

We can see the effect of this truncation error in an example, by using an improperly large step size. Let’s say we want to find the derivative of \(f(x) = cos(x)\) at point \(x=1\). Basic calculus tells us that it should be equals to \(-sin(1) = 0.84147\), but the result is obviously a bit different.

# let d =

let _eps = 0.1 in

let diff f x = (f (x +. _eps) -. f x) /. _eps in

diff Maths.cos 1.

val d : float = -0.867061844425624506

Another source of error is the round-off error. It is caused by representing numbers approximately in numerical computation during this process. We need to calculate \(f(x+h) - f(x)\), the subtraction of two almost identical number. That could lead to a large round-off errors in a computer. For example, let’s choose a very small step size this time:

# let d =

let _eps = 5E-16 in

let diff f x = (f (x +. _eps) -. f x) /. _eps in

diff Maths.cos 1.

val d : float = -0.888178419700125121

It is still significantly different from the expected result. Actually if we use a even smaller step size \(1e-16\), the result becomes 0, which means the round-off error is large enough that \(f(x)\) and \(f(x+h)\) are deemed the same by the computer.

Besides these sources of error, the numerical differentiation method is also slow due to requiring multiple evaluations of function \(f\). Some discussion about numerically solving derivative-related problems is also covered in the Ordinary Differentiation Equation chapter, where we focus on introducing solving these equations numerically, and how the impact of these errors can be reduced.

Symbolic Differentiation

Symbolic Differentiation is the opposite of numerical solution. It does not involve numerical computation, only math symbol manipulation. The rules we have introduced are actually expressed in symbols. Think about this function: \(f(x_0, x_1, x_2) = x_0 * x_1 * x_2\). If we compute \(\nabla~f\) symbolically, we end up with:

\[\nabla~f = (\frac{\partial~f}{\partial~x_0}, \frac{\partial~f}{\partial~x_1}, \frac{\partial~f}{\partial~x_2}) = (x_1 * x_2, x_0 * x_2, x_1 * x_2).\]It is nice and accurate, leaving limited space for numerical errors. However, you can try to extend the number of variables from 3 to a large number \(n\), which means \(f(x) = \prod_{i=0}^{n-1}x_i\), and then try to perform the symbolic differentiation again.

The point is that, symbolic computations tend to give a very large and complex result for even simple functions. It’s easy to have duplicated common sub computations, and produce exponentially large symbolic expressions. Therefore, as intuitive as it is, the symbolic differentiation method can easily takes a lot of memory in computer, and it is slow.

The explosion of computation complexity is not the only limitation of symbolic differentiation. In contrast to the numerical differentiation, we have to treat the function in symbolic differentiation as a white box, knowing exactly what is inside of it. This further indicates that it cannot be used for arbitrary functions.

Algorithmic Differentiation

Algorithmic differentiation (AD) is a chain-rule based technique for calculating the derivatives with regards to input variables of functions defined in a computer programme. It is also known as automatic differentiation, though strictly speaking AD does not fully automate differentiation and can sometimes lead to inefficient code.

AD can generate exact results with superior speed and memory usage, therefore highly applicable in various real world applications.

Even though AD also follows the chain rule, it directly applies numerical computation for intermediate results. It is important to point out that AD is neither numerical nor symbolic differentiation.

It takes the best parts of both worlds, as we will see in the next section.

Actually, the reverse mode of AD yields any gradient vector at no more than five times the cost of evaluating the function \(f\) itself.

AD has already been implemented in various popular languages, including the ad in Python, JuliaDiff in Julia, and ADMAT in MATLAB, etc.

In the rest of this chapter, we focus on introducing the AD module in Owl.

How Algorithmic Differentiation Works

We have seen the chain rules being applied on simple functions such as \(y=x^a\). Now let’s check how this rule can be applied to more complex computations. Let’s look at the function below:

\[y(x_0, x_1) = (1 + e^{x_0~x_1 + sin(x_0)})^{-1}.\]This functions is based on a sigmoid function. Our goal is to compute the partial derivative \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_0}\) and \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_1}\).

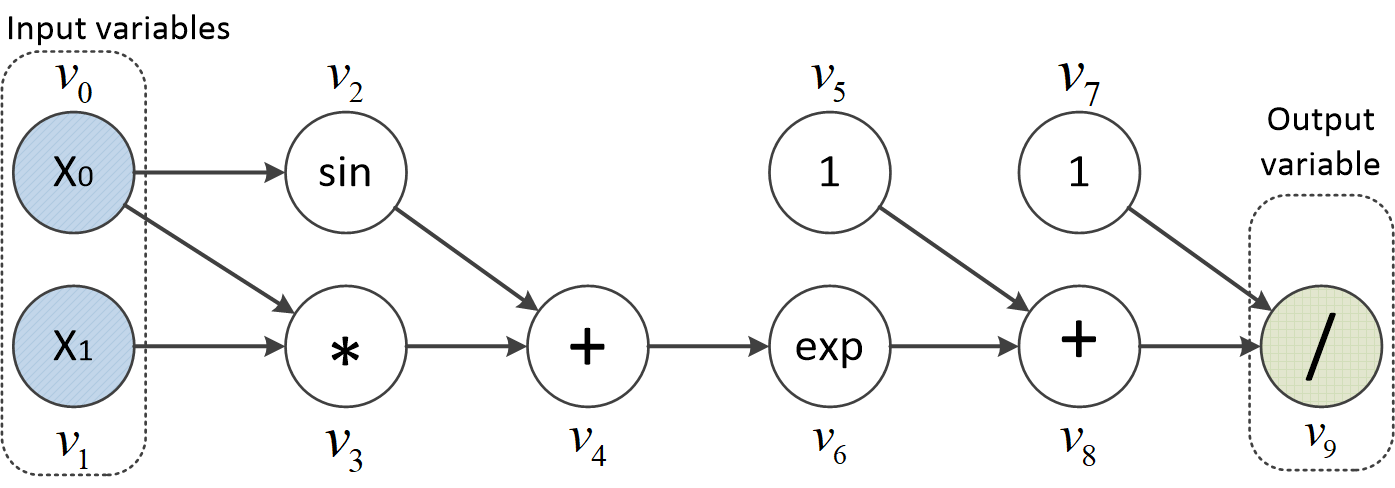

To better illustrate this process, we express the example equation as a graph.

At the right side of the figure, we have the final output \(y\), and at the roots of this graph are input variables.

The nodes between them indicate constants or intermediate variables that are gotten via basic functions such as sine.

All nodes are labelled by \(v_i\).

An edge between two nodes represents an explicit dependency in the computation.

Based on this graphic representation, there are two major ways to apply the chain rules: the forward differentiation mode, and the reverse differentiation mode (not “backward differentiation”, which is a method used for solving ordinary differential equations). Next, we introduce these two methods.

Forward Mode

Our target is to calculate \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_0}\) (partial derivative regarding \(x_1\) should be similar). But hold your horse, let’s start with some earlier intermediate results that might be helpful. For example, what is \(\frac{\partial~x_0}{\partial~x_1}\)? It’s 0. Also, \(\frac{\partial~x_1}{\partial~x_1} = 1\). Now, things gets a bit trickier: what is \(\frac{\partial~v_3}{\partial~x_0}\)? It is a good time to use the chain rule:

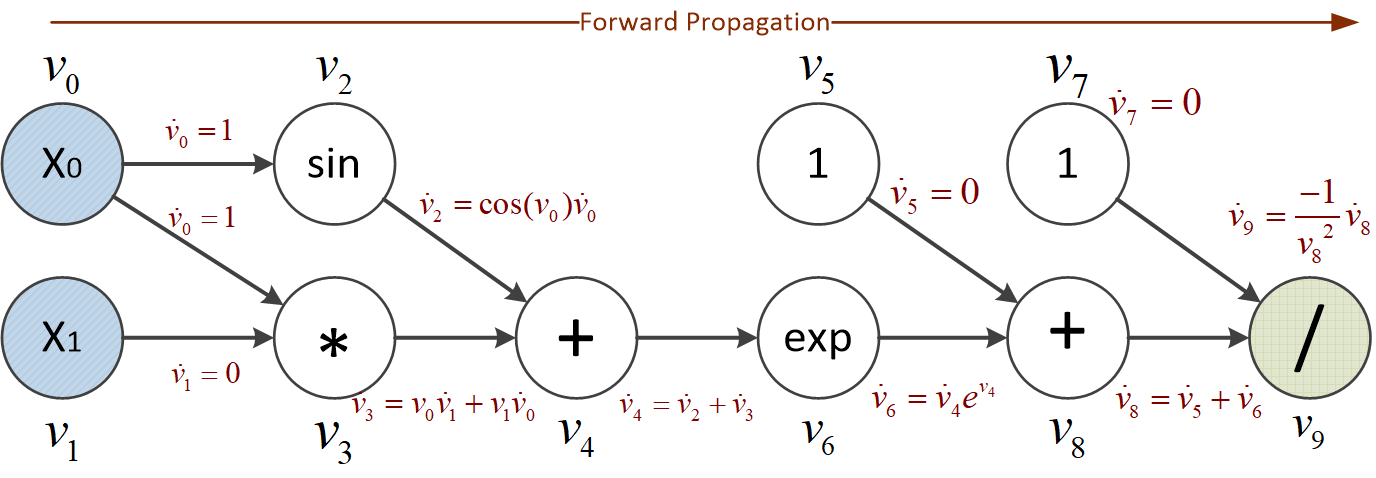

\[\frac{\partial~v_3}{\partial~x_0} = \frac{\partial~(x_0~x_1)}{\partial~x_0} = x_1~\frac{\partial~(x_0)}{\partial~x_0} + x_0~\frac{\partial~(x_1)}{\partial~x_0} = x_1.\]After calculating \(\frac{\partial~v_3}{\partial~x_0}\), we can then processed with derivatives of \(v_5\), \(v_6\), all the way to that of \(v_9\) which is also the output \(y\) we are looking for. This process starts with the input variables, and ends with output variables. Therefore, it is called forward differentiation. We can simplify the math notations in this process by letting \(\dot{v_i}=\frac{\partial~(v_i)}{\partial~x_0}\). The \(\dot{v_i}\) here is called tangent of function \(v_i(x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) with regard to input variable \(x_0\), and the original computation results at each intermediate point is called primal values. The forward differentiation mode is sometimes also called “tangent linear” mode.

Now we can present the full forward differentiation calculation process. Two simultaneous computing processes take place, shown as two separated columns: on the left side is the computation procedure; on the right side shows computation of derivative for each intermediate variable with regard to \(x_0\). Let’s find out \(\dot{y}\) when setting \(x_0 = 1\), and \(x_1 = 1\).

| Step Primal computation | Tangent computation |

|---|---|

| 0 \(v_0 = x_0 = 1\) | \(\dot{v_0}=1\) |

| 1 \(v_1 = x_1 = 1\) | \(\dot{v_1}=0\) |

| 2 \(v_2 = sin(v_0) = 0.84\) | \(\dot{v_2} = cos(v_0)*\dot{v_0} = 0.54 * 1 = 0.54\) |

| 3 \(v_3 = v_0~v_1 = 1\) | \(\dot{v_3} = v_0~\dot{v_1} + v_1~\dot{v_0} = 1 * 0 + 1 * 1 = 1\) |

| 4 \(v_4 = v_2 + v3 = 1.84\) | \(\dot{v_4} = \dot{v_2} + \dot{v_3} = 1.54\) |

| 5 \(v_5 = 1\) | \(\dot{v_5} = 0\) |

| 6 \(v_6 = \exp{(v_4)} = 6.30\) | \(\dot{v_6} = \exp{(v_4)} * \dot{v_4} = 6.30 * 1.54 = 9.70\) |

| 7 \(v_7 = 1\) | \(\dot{v_7} = 0\) |

| 8 \(v_8 = v_5 + v_6 = 7.30\) | \(\dot{v_8} = \dot{v_5} + \dot{v_6} = 9.70\) |

| 9 \(y = v_9 = \frac{1}{v_8}\) | \(\dot{y} = \frac{-1}{v_8^2} * \dot{v_8} = -0.18\) |

This procedure shown in this table can be illustrated below.

Of course, all the numerical computations here are approximated with only two significant figures. We can validate this result with algorithmic differentiation module in Owl. If you don’t understand the code, don’t worry. We will cover the details of this module in later sections.

# open Algodiff.D

# let f x =

let x1 = Mat.get x 0 0 in

let x2 = Mat.get x 0 1 in

Maths.(div (F 1.) (F 1. + exp (x1 * x2 + (sin x1))))

val f : t -> t = <fun>

# let x = Mat.ones 1 2

val x : t = [Arr(1,2)]

# let _ = grad f x |> unpack_arr

- : A.arr =

C0 C1

R0 -0.181974 -0.118142

Reverse Mode

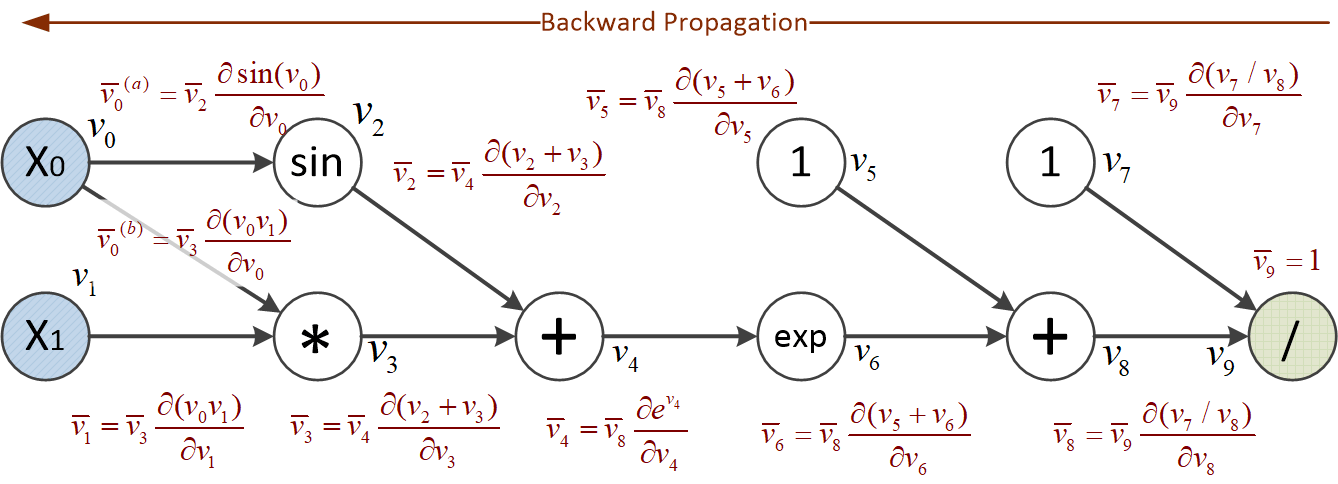

Now let’s rethink about this problem from the other direction, literally. Question remains the same, i.e. calculating \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_0}\). We still follow the same “step by step” idea from the forward mode, but the difference is that, we calculate it backward. For example, here we reduce the problem in this way: since in this graph \(y = v_7 / v_8\), if only we can have \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_7}\) and \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_8}\), then this problem should be one step closer towards my target problem.

First of course, we have \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_9} = 1\), since \(y\) and \(v_9\) are the same. Then how do we get \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_7}\)? Again, time for chain rule:

\[\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_7} = \frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_9} * \frac{\partial~v_9}{\partial~v_7} = 1 * \frac{\partial~v_9}{\partial~v_7} = \frac{\partial~(v_7 / v_8)}{\partial~v_7} = \frac{1}{v_8}.\]Hmm, let’s try to apply a substitution to the terms to simplify this process. Let

\[\bar{v_i} = \frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_i}\]be the derivative of output variable \(y\) with regard to intermediate node \(v_i\). It is called the adjoint of variable \(v_i\) with respect to the output variable \(y\). Using this notation, it can be expressed as:

\[\bar{v_7} = \bar{v_9} * \frac{\partial~v_9}{\partial~v_7} = 1 * \frac{1}{v_8}.\]Note the difference between tangent and adjoint. In the forward mode, we know \(\dot{v_0}\) and \(\dot{v_1}\), then we calculate \(\dot{v_2}\), \(\dot{v_3}\), …. and then finally we have \(\dot{v_9}\), which is the target. Here, we start with knowing \(\bar{v_9} = 1\), and then we calculate \(\bar{v_8}\), \(\bar{v_7}\), …. and then finally we have \(\bar{v_0} = \frac{\partial~y}{\partial~v_0} = \frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_0}\), which is also exactly our target. Again, \(\dot{v_9} = \bar{v_0}\) in this example, given that we are talking about derivative regarding \(x_0\) when we use \(\dot{v_9}\). Following this line of calculation, the reverse differentiation mode is also called adjoint mode.

With that in mind, let’s see the full steps of performing reverse differentiation. First, we need to perform a forward pass to compute the required intermediate values, as shown here.

| Step | Primal computation |

|---|---|

| 0 | \(v_0 = x_0 = 1\) |

| 1 | \(v_1 = x_1 = 1\) |

| 2 | \(v_2 = sin(v_0) = 0.84\) |

| 3 | \(v_3 = v_0~v_1 = 1\) |

| 4 | \(v_4 = v_2 + v3 = 1.84\) |

| 5 | \(v_5 = 1\) |

| 6 | \(v_6 = \exp{(v_4)} = 6.30\) |

| 7 | \(v_7 = 1\) |

| 8 | \(v_8 = v_5 + v_6 = 7.30\) |

| 9 | \(y = v_9 = \frac{1}{v_8}\) |

You might be wondering, this looks the same as the left side. You are right. These two are exactly the same, and we repeat it again to make the point that, this time you cannot perform the calculation with one pass. You must compute the required intermediate results first, and then perform the other “backward pass”, which is the key point in reverse mode.

| Step | Adjoint computation |

|---|---|

| 10 | \(\bar{v_9} = 1\) |

| 11 | \(\bar{v_8} = \bar{v_9}\frac{\partial~(v_7/v_8)}{\partial~v_8} = 1 * \frac{-v_7}{v_8^2} = \frac{-1}{7.30^2} = -0.019\) |

| 12 | \(\bar{v_7} = \bar{v_9}\frac{\partial~(v_7/v_8)}{\partial~v_7} = \frac{1}{v_8} = 0.137\) |

| 13 | \(\bar{v_6} = \bar{v_8}\frac{\partial~v_8}{\partial~v_6} = \bar{v_8} * \frac{\partial~(v_6 + v5)}{\partial~v_6} = \bar{v_8}\) |

| 14 | \(\bar{v_5} = \bar{v_8}\frac{\partial~v_8}{\partial~v_5} = \bar{v_8} * \frac{\partial~(v_6 + v5)}{\partial~v_5} = \bar{v_8}\) |

| 15 | \(\bar{v_4} = \bar{v_6}\frac{\partial~v_6}{\partial~v_4} = \bar{v_8} * \frac{\partial~\exp{(v_4)}}{\partial~v_4} = \bar{v_8} * e^{v_4}\) |

| 16 | \(\bar{v_3} = \bar{v_4}\frac{\partial~v_4}{\partial~v_3} = \bar{v_4} * \frac{\partial~(v_2 + v_3)}{\partial~v_3} = \bar{v_4}\) |

| 17 | \(\bar{v_2} = \bar{v_4}\frac{\partial~v_4}{\partial~v_2} = \bar{v_4} * \frac{\partial~(v_2 + v_3)}{\partial~v_2} = \bar{v_4}\) |

| 18 | \(\bar{v_1} = \bar{v_3}\frac{\partial~v_3}{\partial~v_1} = \bar{v_3} * \frac{\partial~(v_0*v_1)}{\partial~v_1} = \bar{v_4} * v_0 = \bar{v_4}\) |

| 19 | \(\bar{v_{02}} = \bar{v_2}\frac{\partial~v_2}{\partial~v_0} = \bar{v_2} * \frac{\partial~(sin(v_0))}{\partial~v_0} = \bar{v_4} * cos(v_0)\) |

| 20 | \(\bar{v_{03}} = \bar{v_3}\frac{\partial~v_3}{\partial~v_0} = \bar{v_3} * \frac{\partial~(v_0 * v_1)}{\partial~v_0} = \bar{v_4} * v_1\) |

| 21 | \(\bar{v_0} = \bar{v_{02}} + \bar{v_{03}} = \bar{v_4}(cos(v_0) + v_1) = \bar{v_8} * e^{v_4}(0.54 + 1) = -0.019 * e^{1.84} * 1.54 = -0.18\) |

Note that things a bit different for \(x_0\). It is used in both intermediate variables \(v_2\) and \(v_3\). Therefore, we compute the adjoint of \(v_0\) with regard to \(v_2\) (step 19) and \(v_3\) (step 20), and accumulate them together (step 20).

Similar to the forward mode, reverse differentiation process in [] can be clearly shown here.

This result \(\bar{v_0} = -0.18\) agrees what we have have gotten using the forward mode. However, if you still need another fold of insurance, we can use Owl to perform a numerical differentiation. The code would be similar to that of using algorithmic differentiation as shown before.

module D = Owl_numdiff_generic.Make (Dense.Ndarray.D);;

let x = Arr.ones [|2|]

let f x =

let x1 = Arr.get x [|0|] in

let x2 = Arr.get x [|1|] in

Maths.(div 1. (1. +. exp (x1 *. x2 +. (sin x1))))

And then we can get the differentiation result at the point \((x_0, x_1) = (0, 0)\), and it agrees with the previous results.

# D.grad f x

- : D.arr =

C0 C1

R -0.181973 -0.118142

Before we move on, did you notice that we get \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_1}\) for “free” while calculating \(\frac{\partial~y}{\partial~x_0}\). Noticing this will help you to understand the next section, about how to decide which mode (forward or backward) to use in practice.

Forward or Reverse?

Since both modes can be used to differentiate a function, the natural question is which mode we should choose in practice. The short answer is: it depends on your function. In general, given a function that you want to differentiate, the rule of thumb is:

- if the number of input variables is far larger than that of the output variables, then use reverse mode;

- if the number of output variables is far larger than that of the input variables, then use forward mode.

For each input variable, we need to seed individual variable and perform one forward pass. The number of forward passes increase linearly as the number of inputs increases. However, for backward mode, no matter how many inputs there are, one backward pass can give us all the derivatives of the inputs. I guess now you understand why we need to use backward mode for f. One real-world example of f is machine learning and neural network algorithms, wherein there are many inputs but the output is often one scalar value from loss function.

Backward mode needs to maintain a directed computation graph in the memory so that the errors can propagate back; whereas the forward mode does not have to do that due to the algebra of dual numbers. Later we will show example about choosing between these two methods.

A Strawman AD Engine

Surely you don’t want to make these tables every time you are faced with a new computation. Now that you understand how to use forward and reverse propagation to do algorithmic differentiation, let’s look at how to do it with computer programmes. In this section, we will introduce how to implement the differentiation modes using pure OCaml code. Of course, these will be elementary straw man implementations compared to the industry standard module provided by Owl, but nevertheless are important to the understanding of the latter.

We will again use the example function as example, and we limit the computation in our small AD engine to only these basic operations: add, div, mul.

Simple Forward Implementation

How can we represent the table? An intuitive answer is to build a table when traversing the computation graph. However, that’s not a scalable: what if there are hundreds and thousands of computation steps? A closer look at the table shows that an intermediate node actually only need to know the computation results (primal value and tangent value) of its parents nodes to compute its own results. Based on this observation, we can define a data type that preserve these two values:

type df = {

mutable p: float;

mutable t: float

}

let primal df = df.p

let tangent df = df.t

And now we can define operators that accept type df as input and outputs the same type:

let sin_ad x =

let p = primal x in

let t = tangent x in

let p' = Owl_maths.sin p in

let t' = (Owl_maths.cos p) *. t in

{p=p'; t=t'}

The core part of this function is to define how to compute its function value p' and derivative value t' based on the input df data.

Now you can easily extend it towards the exp operation:

let exp_ad x =

let p = primal x in

let t = tangent x in

let p' = Owl_maths.exp p in

let t' = p' *. t in

{p=p'; t=t'}

But what about operators that accept multiple inputs? Let’s see multiplication.

let mul_ad a b =

let pa = primal a in

let ta = tangent a in

let pb = primal b in

let tb = tangent b in

let p' = pa *. pb in

let t' = pa *. tb +. ta *. pb in

{p=p'; t=t'}

Though it require a bit more unpacking, its forward computation and derivative function are simple enough.

Similarly, you can extend that towards similar operations: the add and div.

let add_ad a b =

let pa = primal a in

let ta = tangent a in

let pb = primal b in

let tb = tangent b in

let p' = pa +. pb in

let t' = ta +. tb in

{p=p'; t=t'}

let div_ad a b =

let pa = primal a in

let ta = tangent a in

let pb = primal b in

let tb = tangent b in

let p' = pa /. pb in

let t' = (ta *. pb -. tb *. pa) /. (pb *. pb) in

{p=p'; t=t'}

Based on these functions, we can provide a tiny wrapper named diff:

let diff f =

let f' x y =

let r = f x y in

primal r, tangent r

in

f'

And that’s all! Now we can do differentiation on our previous example.

let x0 = {p=1.; t=1.}

let x1 = {p=1.; t=0.}

These are inputs.

We know the tangent of x1 with regard to x0 is zero, and so are the other constants used in the computation.

# let f x0 x1 =

let v2 = sin_ad x0 in

let v3 = mul_ad x0 x1 in

let v4 = add_ad v2 v3 in

let v5 = {p=1.; t=0.} in

let v6 = exp_ad v4 in

let v7 = {p=1.; t=0.} in

let v8 = add_ad v5 v6 in

let v9 = div_ad v7 v8 in

v9

val f : df -> df -> df = <fun>

# let pri, tan = diff f x0 x1

val pri : float = 0.13687741466075895

val tan : float = -0.181974376561731321

The results are just as calculated in the previous section.

Simple Reverse Implementation

The reverse mode is a bit more complex. As shown in the previous section, forward mode only needs one pass, but the reverse mode requires two passes, a forward pass followed by a backward pass. This further indicates that, besides computing primal values, we also need to “remember” the operations along the forward pass, and then utilise these information in the backward pass. There are multiple ways to do that, e.g. a stack or graph structure. What we choose here is bit different though. Let’s start with the data types we use.

type dr = {

mutable p: float;

mutable a: float ref;

mutable adj_fun : float ref -> (float * dr) list -> (float * dr) list

}

let primal dr = dr.p

let adjoint dr = dr.a

let adj_fun dr = dr.adj_fun

The p is for primal while a stands for adjoint. It’s easy to understand.

The adj_fun is a bit tricky. Let’s see an example:

let sin_ad dr =

let p = primal dr in

let p' = Owl_maths.sin p in

let adjfun' ca t =

let r = !ca *. (Owl_maths.cos p) in

(r, dr) :: t

in

{p=p'; a=ref 0.; adj_fun=adjfun'}

It’s an implementation of sin operation.

The adj_fun here can be understood as a placeholder for the adjoint value we don’t know yet in the forward pass.

The t is a stack of intermediate nodes to be processed in the backward process.

It says that, if I have the adjoint value ca, I can then get the new adjoint value of my parents r.

This result, together with the original data dr, is pushed to the stack t.

This stack is implemented in OCaml list.

Let’s then look at the mul operation with two variables:

let mul_ad dr1 dr2 =

let p1 = primal dr1 in

let p2 = primal dr2 in

let p' = Owl_maths.mul p1 p2 in

let adjfun' ca t =

let r1 = !ca *. p2 in

let r2 = !ca *. p1 in

(r1, dr1) :: (r2, dr2) :: t

in

{p = p'; a = ref 0.; adj_fun = adjfun'}

The difference is that, this time both of its parents are added to the task stack. For the input data, we need a helper function:

let make_reverse v =

let a = ref 0. in

let adj_fun _a t = t in

{p=v; a; adj_fun}

With this function, we can perform the forward pass like this:

# let x = make_reverse 1.

val x : dr = {p = 1.; a = {contents = 0.}; adj_fun = <fun>}

# let y = make_reverse 2.

val y : dr = {p = 2.; a = {contents = 0.}; adj_fun = <fun>}

# let v = mul_ad (sin_ad x) y

val v : dr = {p = 1.68294196961579301; a = {contents = 0.}; adj_fun = <fun>}

After the forward pass, we have the primal values at each intermediate node, but their adjoint values are all set to zero, since we don’t know them yet.

And we have this adjoin function. Noting that executing this function would create a list of past computations, which in turn contains its own adj_fun.

This resulting adj_fun remembers all the required information, and know we need to recursively calculate the adjoint values we want.

let rec reverse_push xs =

match xs with

| [] -> ()

| (v, dr) :: t ->

let aa = adjoint dr in

let adjfun = adj_fun dr in

aa := !aa +. v;

let stack = adjfun aa t in

reverse_push stack

The reverse_push does exactly that. Starting from a list, it gets the top element dr, gets the adjoint value we already calculated aa, updates it with v, and then gets the adj_fun. Now that we know the adjoint value, we can use that as input parameter to the adj_fun to execute the data of current task and recursively execute more nodes until the task stack is empty.

Now, let’s add some other required operations basically by copy and paste:

let exp_ad dr =

let p = primal dr in

let p' = Owl_maths.exp p in

let adjfun' ca t =

let r = !ca *. (Owl_maths.exp p) in

(r, dr) :: t

in

{p=p'; a=ref 0.; adj_fun=adjfun'}

let add_ad dr1 dr2 =

let p1 = primal dr1 in

let p2 = primal dr2 in

let p' = Owl_maths.add p1 p2 in

let adjfun' ca t =

let r1 = !ca in

let r2 = !ca in

(r1, dr1) :: (r2, dr2) :: t

in

{p = p'; a = ref 0.; adj_fun = adjfun'}

let div_ad dr1 dr2 =

let p1 = primal dr1 in

let p2 = primal dr2 in

let p' = Owl_maths.div p1 p2 in

let adjfun' ca t =

let r1 = !ca /. p2 in

let r2 = !ca *. (-.p1) /. (p2 *. p2) in

(r1, dr1) :: (r2, dr2) :: t

in

{p = p'; a = ref 0.; adj_fun = adjfun'}

We can express the differentiation function diff with the reverse mode, with first a forward pass and then a backward pass.

let diff f =

let f' x =

(* forward pass *)

let r = f x in

(* backward pass *)

reverse_push [(1., r)];

(* get result values *)

let x0, x1 = x in

primal x0, !(adjoint x0), primal x1, !(adjoint x1)

in

f'

Now we can do the calculation, which are the same as before, and the only difference is the way to build constant values.

# let x1 = make_reverse 1.

val x1 : dr = {p = 1.; a = {contents = 0.}; adj_fun = <fun>}

# let x0 = make_reverse 1.

val x0 : dr = {p = 1.; a = {contents = 0.}; adj_fun = <fun>}

# let f x =

let x0, x1 = x in

let v2 = sin_ad x0 in

let v3 = mul_ad x0 x1 in

let v4 = add_ad v2 v3 in

let v5 = make_reverse 1. in

let v6 = exp_ad v4 in

let v7 = make_reverse 1. in

let v8 = add_ad v5 v6 in

let v9 = div_ad v7 v8 in

v9

val f : dr * dr -> dr = <fun>

Now let’s do the differentiation:

# let pri_x0, adj_x0, pri_x1, adj_x1 = diff f (x0, x1)

val pri_x0 : float = 1.

val adj_x0 : float = -0.181974376561731321

val pri_x1 : float = 1.

val adj_x1 : float = -0.118141988016545588

Again, their adjoint values are just as expected.

Unified Implementations

We have shown how to implement forward and reverse AD from scratch separately. But in the real world applications, we often need a system that supports both differentiation modes. How can we build it then?

We start with combining the previous two record data types df and dr into a new data type t and its related operations:

type t =

| DF of float * float

| DR of float * float ref * adjoint

and adjoint = float ref -> (float * t) list -> (float * t) list

let primal = function

| DF (p, _) -> p

| DR (p, _, _) -> p

let tangent = function

| DF (_, t) -> t

| DR (_, _, _) -> failwith "error: no tangent for DR"

let adjoint = function

| DF (_, _) -> failwith "error: no adjoint for DF"

| DR (_, a, _) -> a

let make_forward p a = DF (p, a)

let make_reverse p =

let a = ref 0. in

let adj_fun _a t = t in

DR (p, a, adj_fun)

let rec reverse_push xs =

match xs with

| [] -> ()

| (v, x) :: t ->

(match x with

| DR (_, a, adjfun) ->

a := !a +. v;

let stack = adjfun a t in

reverse_push stack

| _ -> failwith "error: unsupported type")

Now we can operate on one unified data type. Based on this new data type, we can then combine the forward and reverse mode into one single function, using a match clause.

let sin_ad x =

let ff = Owl_maths.sin in

let df p t = (Owl_maths.cos p) *. t in

let dr p a = !a *. (Owl_maths.cos p) in

match x with

| DF (p, t) ->

let p' = ff p in

let t' = df p t in

DF (p', t')

| DR (p, _, _) ->

let p' = ff p in

let adjfun' a t =

let r = dr p a in

(r, x) :: t

in

DR (p', ref 0., adjfun')

The code is mostly taken from the previous two implementations, so should be not very alien to you now. Similarly we can also build the multiplication operator:

let mul_ad xa xb =

let ff = Owl_maths.mul in

let df pa pb ta tb = pa *. tb +. ta *. pb in

let dr pa pb a = !a *. pb, !a *. pa in

match xa, xb with

| DF (pa, ta), DF (pb, tb) ->

let p' = ff pa pb in

let t' = df pa pb ta tb in

DF (p', t')

| DR (pa, _, _), DR (pb, _, _) ->

let p' = ff pa pb in

let adjfun' a t =

let ra, rb = dr pa pb a in

(ra, xa) :: (rb, xb) :: t

in

DR (p', ref 0., adjfun')

| _, _ -> failwith "unsupported op"

Now before moving forward, let’s pause and think about what’s so different among different math functions.

First, they may take different number of input arguments; they could be unary functions or binary functions.

Second, they have different computation rules.

Specifically, three type of computations are involved:

ff, which computes the primal value; df, which computes the tangent value; and dr, which computes the adjoint value.

The rest are mostly fixed.

Based on this observation, we can utilise the first-class citizen in OCaml, the “module”, to reduce a lot of copy and paste in our code. We can start with two types of modules: unary and binary:

module type Unary = sig

val ff : float -> float

val df : float -> float -> float

val dr : float -> float ref -> float

end

module type Binary = sig

val ff : float -> float -> float

val df : float -> float -> float -> float -> float

val dr : float -> float -> float ref -> float * float

end

They express both points of difference: first, the two modules differentiate between unary and binary ops; second, each module represents the three core operations: ff, df, and dr.

We can focus on the computation logic of each computation in each module:

module Sin = struct

let ff = Owl_maths.sin

let df p t = (Owl_maths.cos p) *. t

let dr p a = !a *. (Owl_maths.cos p)

end

module Exp = struct

let ff = Owl_maths.exp

let df p t = (Owl_maths.exp p) *. t

let dr p a = !a *. (Owl_maths.exp p)

end

module Mul = struct

let ff = Owl_maths.mul

let df pa pb ta tb = pa *. tb +. ta *. pb

let dr pa pb a = !a *. pb, !a *. pa

end

module Add = struct

let ff = Owl_maths.add

let df _pa _pb ta tb = ta +. tb

let dr _pa _pb a = !a, !a

end

module Div = struct

let ff = Owl_maths.div

let df pa pb ta tb = (ta *. pb -. tb *. pa) /. (pb *. pb)

let dr pa pb a =

!a /. pb, !a *. (-.pa) /. (pb *. pb)

end

Now we can provide a template to build math functions:

let unary_op (module U: Unary) = fun x ->

match x with

| DF (p, t) ->

let p' = U.ff p in

let t' = U.df p t in

DF (p', t')

| DR (p, _, _) ->

let p' = U.ff p in

let adjfun' a t =

let r = U.dr p a in

(r, x) :: t

in

DR (p', ref 0., adjfun')

let binary_op (module B: Binary) = fun xa xb ->

match xa, xb with

| DF (pa, ta), DF (pb, tb) ->

let p' = B.ff pa pb in

let t' = B.df pa pb ta tb in

DF (p', t')

| DR (pa, _, _), DR (pb, _, _) ->

let p' = B.ff pa pb in

let adjfun' a t =

let ra, rb = B.dr pa pb a in

(ra, xa) :: (rb, xb) :: t

in

DR (p', ref 0., adjfun')

| _, _ -> failwith "unsupported op"

Each template accepts a module, and then returns the function we need. Let’s see how it works with concise code.

let sin_ad = unary_op (module Sin : Unary)

let exp_ad = unary_op (module Exp : Unary)

let mul_ad = binary_op (module Mul : Binary)

let add_ad = binary_op (module Add: Binary)

let div_ad = binary_op (module Div : Binary)

As you can expect, the diff function can also be implemented in a combined way. In this implementation we focus on the tangent and adjoint value of x0 only.

let diff f =

let f' x =

let x0, x1 = x in

match x0, x1 with

| DF (_, _), DF (_, _) ->

f x |> tangent

| DR (_, _, _), DR (_, _, _) ->

let r = f x in

reverse_push [(1., r)];

!(adjoint x0)

| _, _ -> failwith "error: unsupported operator"

in

f'

That’s all. We can move on once again to our familiar examples.

# let x0 = make_forward 1. 1.

val x0 : t = DF (1., 1.)

# let x1 = make_forward 1. 0.

val x1 : t = DF (1., 0.)

# let f_forward x =

let x0, x1 = x in

let v2 = sin_ad x0 in

let v3 = mul_ad x0 x1 in

let v4 = add_ad v2 v3 in

let v5 = make_forward 1. 0. in

let v6 = exp_ad v4 in

let v7 = make_forward 1. 0. in

let v8 = add_ad v5 v6 in

let v9 = div_ad v7 v8 in

v9

val f_forward : t * t -> t = <fun>

# diff f_forward (x0, x1)

- : float = -0.181974376561731321

That’s just forward mode. With only tiny change of how the variables are constructed, we can also do the reverse mode.

# let x0 = make_reverse 1.

val x0 : t = DR (1., {contents = 0.}, <fun>)

# let x1 = make_reverse 1.

val x1 : t = DR (1., {contents = 0.}, <fun>)

# let f_reverse x =

let x0, x1 = x in

let v2 = sin_ad x0 in

let v3 = mul_ad x0 x1 in

let v4 = add_ad v2 v3 in

let v5 = make_reverse 1. in

let v6 = exp_ad v4 in

let v7 = make_reverse 1. in

let v8 = add_ad v5 v6 in

let v9 = div_ad v7 v8 in

v9

val f_reverse : t * t -> t = <fun>

# diff f_reverse (x0, x1)

- : float = -0.181974376561731321

Once again, the results agree and are just as expected.

Forward and Reverse Propagation API

So far we have talked a lot about what is algorithmic differentiation and how it works, with theory, example illustration, and code. Now finally let’s turn to using it in Owl. Owl provides both numerical differentiation (in Numdiff.Generic module) and algorithmic differentiation (in Algodiff.Generic module). We have briefly used them in previous sections to validate the calculation results of our manual forward and reverse differentiation examples.

Algorithmic Differentiation is a core module built in Owl, which is one of Owl’s special features among other similar numerical libraries.

Algodiff.Generic is a functor that accepts a Ndarray modules.

By plugging in Dense.Ndarray.S and Dense.Ndarray.D modules we can have AD modules that supports float32 and float64 precision respectively.

module S = Owl_algodiff_generic.Make (Owl_algodiff_primal_ops.S)

module D = Owl_algodiff_generic.Make (Owl_algodiff_primal_ops.D)

This Owl_algodiff_primal_ops module here might seem unfamiliar to you, but in essence it is mostly an alias of the Ndarray module, with certain matrix and linear algebra functions added in.

We will mostly use the double precision Algodiff.D module, but of course using other choices is also perfectly fine.

Expressing Computation

Let’s look at the the previous example, and express it with the AD module. Normally, the code below should do.

open Owl

let f x =

let x0 = Mat.get x 0 0 in

let x1 = Mat.get x 0 1 in

Owl_maths.(1. /. (1. +. exp (sin x0 +. x0 *. x1)))

This function accepts a vector and returns a float value, which is exactly what we are looking for. However, the problem is that we cannot directly differentiate this programme. Instead, we need to do some minor but important change:

module AD = Algodiff.D

let f x =

let x0 = AD.Mat.get x 0 0 in

let x1 = AD.Mat.get x 0 1 in

AD.Maths.((F 1.) / (F 1. + exp (sin x0 + x0 * x1)))

This function looks very similar, but now we are using the operators provided by the AD module, including the get operation and math operations.

In AD, all the input/output are of type AD.t. There is no difference between scalar, matrix, or ndarray for the type checking.

The F is special packing mechanism in AD. It makes a type t float. Think about wrapping a float number inside a container that can be recognised in this factory called “AD”. And then this factory can produce the differentiation result you want.

The Arr operator is similar. It wraps an ndarray (or matrix) inside this same container.

And as you can guess, there are also unpacking mechanisms. When this AD factory produces some result, to see the result you need to first unwrap this container with the functions unpack_flt and unpack_arr.

For example, we can directly execute the AD functions, and the results need to be unpacked before being used.

open AD

# let input = Arr (Dense.Matrix.D.ones 1 2)

# let result = f input |> unpack_flt

val result : float = 0.13687741466075895

Despite this slightly cumbersome number packing mechanism, we can now perform the forward and reverse propagation on this computation in Owl, as will be shown next.

Example: Forward Mode

The forward mode is implemented with the make_forward and tangent function:

val make_forward : t -> t -> int -> t

val tangent : t -> t

The forward process is straightforward.

open AD

# let x = make_forward input (F 1.) (tag ());; (* seed the input *)

# let y = f x;; (* forward pass *)

# let y' = tangent y;; (* get all derivatives *)

All the derivatives are ready whenever the forward pass is finished, and they are stored as tangent values in y.

We can retrieve the derivatives using tangent function.

Example: Reverse Mode

The reverse mode consists of two parts:

val make_reverse : t -> int -> t

val reverse_prop : t -> t -> unit

Let’s look at the code snippet below.

open AD

# let x = Mat.ones 1 2;; (* generate random input *)

# let x' = make_reverse x (tag ());; (* init the reverse mode *)

# let y = f x';; (* forward pass to build computation graph *)

# let _ = reverse_prop (F 1.) y;; (* backward pass to propagate error *)

# let y' = adjval x';; (* get the gradient value of f *)

- : A.arr =

C0 C1

R0 -0.181974 -0.118142

The make_reverse function does two things for us: 1) wrapping x into type t that Algodiff can process 2) generating a unique tag for the input so that input numbers can have nested structure.

By calling f x', we construct the computation graph of f and the graph structure is maintained in the returned result y. Finally, reverse_prop function propagates the error back to the inputs.

In the end, the gradient of f is stored in the adjacent value of x', and we can retrieve that with adjval function.

The result agrees with what we have calculated manually.

High-Level APIs

What we have seen is the basic of AD modules.

There might be cases you do need to operate these low-level functions to write up your own applications (e.g., implementing a neural network), then knowing the mechanisms behind the scene is definitely a big plus.

However, using these complex low level function hinders daily use of algorithmic differentiation in numerical computation task.

In reality, you don’t really need to worry about forward or reverse mode if you simply use high-level APIs such as diff, grad, hessian, etc.

They are all built on the forward or reverse mode that we have seen, but provide clean interfaces, making a lot of details transparent to users.

In this section we will introduce how to use these high level APIs.

Derivative and Gradient

The most basic and commonly used differentiation functions is used for calculating the derivative of a function.

The AD module provides diff function for this task.

Given a function f that takes a scalar as input and also returns a scalar value, we can calculate its derivative at a point x by diff f x, as shown in this function signature.

val diff : (t -> t) -> t -> t

The physical meaning of derivative is intuitive. The function f can be expressed as a curve in a cartesian coordinate system, and the derivative at a point is the tangent on a function at this point.

It also indicate the rate of change at this point.

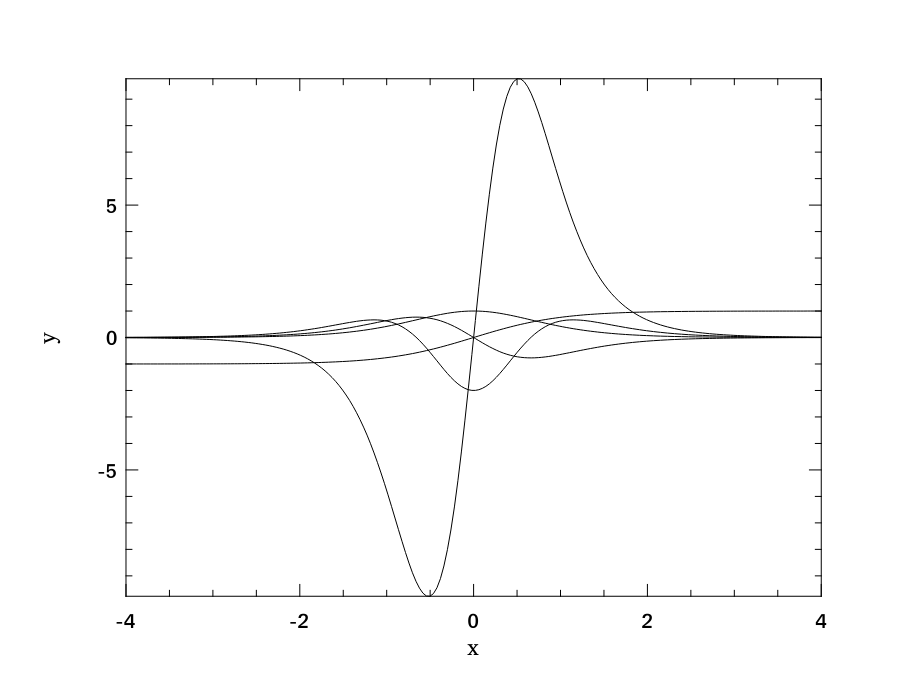

Suppose we define a function f0 to be the triangular function tanh, we can calculate its derivative at position \(x=0.1\) by simply calling:

open Algodiff.D

let f0 x = Maths.(tanh x)

let d = diff f0 (F 0.1)

Moreover, the AD module is much more than that; we can easily chain multiple diff together to get a function’s high order derivatives.

For example, we can get the first to fourth order derivatives of f0 by using the concise code below.

let f0 x = Maths.(tanh x);;

let f1 = diff f0;;

let f2 = diff f1;;

let f3 = diff f2;;

let f4 = diff f3;;

We can further plot these five functions using Owl, and the result is show here.

let map f x = Owl.Mat.map (fun a -> a |> pack_flt |> f |> unpack_flt) x;;

let x = Owl.Mat.linspace (-4.) 4. 200;;

let y0 = map f0 x;;

let y1 = map f1 x;;

let y2 = map f2 x;;

let y3 = map f3 x;;

let y4 = map f4 x;;

let h = Plot.create "plot_00.png" in

Plot.plot ~h x y0;

Plot.plot ~h x y1;

Plot.plot ~h x y2;

Plot.plot ~h x y3;

Plot.plot ~h x y4;

Plot.output h;;

If you want, you can play with other functions, such as \(\frac{1-e^{-x}}{1+e^{-x}}\) to see what its derivatives look like.

A close-related idea to derivative is the gradient.

As we have introduced, gradient generalises derivatives to multivariate functions.

Therefore, for a function that accepts a vector (where each element is a variable) and returns a scalar, we can use the grad function to find its gradient at a point.

Imagine a 3D surface. At each points on this surface, a gradient consists of three element that each represents the derivative along the x, y or z axis.

This vector shows the direction and magnitude of maximum change of a multivariate function.

One important application of gradient is the gradient descent, a widely used technique to find minimum values on a function. The basic idea is that, at any point on the surface, we calculate the gradient to find the current direction of maximal change at this point, and move the point along this direction by a small step, and then repeat this process until the point cannot be further moved. We will talk about it in detail in the Regression and Optimisation chapters in our book.

Jacobian

Just like gradient extends derivative, the gradient can also be extended to the Jacobian matrix.

The grad can be applied on functions with vector as input and scalar as output.

The jacobian function on the other hand, deals with functions that has both input and output of vectors.

Suppose the input vector is of length \(n\), and contains \(m\) output variables, the jacobian matrix is defined as:

The intuition of Jacobian is similar to that of the gradient. At a particular point in the domain of the target function, If you give it a small change in the input vector, the Jacobian matrix shows how the output vector changes. One application field of Jacobian is in the analysis of dynamical systems. In a dynamic system \(\vec{y}=f(\vec{x})\), suppose \(f: \mathbf{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbf{R}^m\) is differentiable and its jacobian is \(\mathbf{J}\).

According to the Hartman-Grobman theorem, the stability of a dynamic system near a stationary point is decided by the eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{J}\). It is stable if all the eigenvalues have negative real parts, otherwise its unstable, with the exception that when the largest real part of the eigenvalues is zero. In that case, the stability cannot be decided by eigenvalues.

Let’s revise the two-body problem from Ordinary Differential Equation Chapter. This dynamic system is described by a group of differential equations:

\[y_0^{'} = y_2,\] \[y_1^{'} = y_3,\] \[y_2^{'} = -\frac{y_0}{r^3},\] \[y_3^{'} = -\frac{y_1}{r^3},\]We can express this system with code:

open Algodiff.D

let f y =

let y0 = Mat.get y 0 0 in

let y1 = Mat.get y 0 1 in

let y2 = Mat.get y 0 2 in

let y3 = Mat.get y 0 3 in

let r = Maths.(sqrt ((sqr y0) + (sqr y1))) in

let y0' = y2 in

let y1' = y3 in

let y2' = Maths.( neg y0 / pow r (F 3.)) in

let y3' = Maths.( neg y1 / pow r (F 3.)) in

let y' = Mat.ones 1 4 in

let y' = Mat.set y' 0 0 y0' in

let y' = Mat.set y' 0 1 y1' in

let y' = Mat.set y' 0 2 y2' in

let y' = Mat.set y' 0 3 y3' in

y'

For this functions \(f: \mathbf{R}^4 \rightarrow \mathbf{R}^4\), we can then find its Jacobian matrix. Suppose the given point of interest of where all four input variables equals one. Then we can use the Algodiff.D.jacobian function in this way.

let y = Mat.ones 1 4

let result = jacobian f y

let j = unpack_arr result;;

- : A.arr =

C0 C1 C2 C3

R0 0 0 1 0

R1 0 0 0 1

R2 0.176777 0.53033 0 0

R3 0.53033 0.176777 0 0

Next, we find the eigenvalues of this jacobian matrix with the Linear Algebra module in Owl that we have introduced in previous chapter.

let eig = Owl_linalg.D.eigvals j

val eig : Owl_dense_matrix_z.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3

R0 (0.840896, 0i) (-0.840896, 0i) (0, 0.594604i) (0, -0.594604i)

It turns out that one of the eigenvalue is real and positive, so at current point the system is unstable.

Hessian and Laplacian

Another way to extend the gradient is to find the second order derivatives of a multivariate function which takes \(n\) input variables and outputs a scalar. Its second order derivatives can be organised as a matrix:

\[\mathbf{H}(y) = \left[ \begin{matrix} \frac{\partial^2~y_1}{\partial~x_1^2} & \frac{\partial^2~y_1}{\partial~x_1~x_2} & \ldots & \frac{\partial^2~y_1}{\partial~x_1~x_n} \\ \frac{\partial^2~y_2}{\partial~x_2~x_1} & \frac{\partial^2~y_2}{\partial~x_2^2} & \ldots & \frac{\partial^2~y_2}{\partial~x_2~x_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ldots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial^2~y_m}{\partial^2~x_n~x_1} & \frac{\partial^2~y_m}{\partial~x_n~x_2} & \ldots & \frac{\partial^2~y_m}{\partial~x_n^2} \end{matrix} \right]\]This matrix is called the Hessian Matrix. As an example of using it, consider the newton’s method. It is also used for solving the optimisation problem, i.e. to find the minimum value on a function. Instead of following the direction of the gradient, the newton method combines gradient and second order gradients: \(\frac{\nabla~f(x_n)}{\nabla^{2}~f(x_n)}\). Specifically, starting from a random position \(x_0\), and it can be iteratively updated by repeating this procedure until converge.

\[x_{n+1} = x_n - \alpha~\mathbf{H}^{-1}\nabla~f(x_n)\]This process can be easily represented using the Algodiff.D.hessian function.

open Algodiff.D

let rec newton ?(eta=F 0.01) ?(eps=1e-6) f x =

let g = grad f x in

let h = hessian f x in

if (Maths.l2norm' g |> unpack_flt) < eps then x

else newton ~eta ~eps f Maths.(x - eta * g *@ (inv h))

We can then apply this method on a two dimensional triangular function to find one of the local minimum values, staring from a random initial point. Note that here the functions has to take a vector as input and output a scalar. We will come back to this method in the in Optimisation chapter with more details.

let _ =

let f x = Maths.(cos x |> sum') in

newton f (Mat.uniform 1 2)

Another useful and related function is laplacian, it calculate the Laplacian operator \(\nabla^2~f\), which is the the trace of the Hessian matrix:

In Physics, the Laplacian can represent the flux density of the gradient flow of a function, e.g. the moving rate of a chemical in a fluid. Therefore, differential equations that contains Laplacian are frequently used in many fields to describe physical systems, such as the gravitational potentials, the fluid flow, wave propagation, and electric field, etc.

Other APIs

Besides, there are also many helper functions, such as jacobianv for calculating jacobian vector product; diff' for calculating both f x and diff f x, etc.

They will come handy in certain cases for the programmers.

Besides the functions we have already introduced, the complete list of APIs can be found in the table below.

| API name | Explanation |

|---|---|

diff' |

similar to diff, but return (f x, diff f x) |

grad' |

similar to grad, but return (f x, grad f x) |

jacobian' |

similar to jacobian, but return (f x, jacobian f x) |

jacobianv |

jacobian vector product of f : (vector -> vector) at x along v; it calcultes (jacobian x) v |

jacobianv' |

similar to jacobianv, but return (f x, jacobianv f x) |

jacobianTv |

it calculates transpose ((jacobianv f x v)) |

jacobianTv' |

similar to jacobianTv, but return (f x, transpose (jacobianv f x v)) |

hessian' |

hessian vector product of f : (scalar -> scalar) at x along v; it calculates (hessian x) v |

hessianv' |

similar to hessianv, but return (f x, hessianv f x v) |

laplacian' |

similar to laplacian, but return (f x, laplacian f x) |

gradhessian |

return (grad f x, hessian f x), f : (scalar -> scalar) |

gradhessian' |

return (f x, grad f x, hessian f x) |

gradhessianv |

return (grad f x v, hessian f x v) |

gradhessianv' |

return (f x, grad f x v, hessian f x v) |

Differentiation is an important topic in scientific computing, and therefore is not limited to only this chapter in our book. As we have already shown in previous examples, we use AD in the newton method to find extreme values in optimisation problem in the Optimisation chapter. It is also used in the Regression chapter to solve the linear regression problem with gradient descent. More importantly, the algorithmic differentiation is core module in many modern deep neural libraries such as PyTorch. The neural network module in Owl benefit a lot from our solid AD module. We will elaborate these aspects in the following chapters. Stay tuned!

Internal of Algorithmic Differentiation

Go Beyond Simple Implementation

Now that you know the basic implementation of forward and reverse differentiation, and you have also seen the high level APIs that Owl provides. You might be wondering, how are these APIs implemented in Owl?

It turns out that, the simple implementations we have are not very far away from the industry-level implementations in Owl. There are of course many details that need to be taken care of in Owl, but by now you should be able to understand the gist of it. Without digging too deep into the code details, in this section we give an overview of some of the key differences between the Owl implementation and the simple version we built in the previous sections.

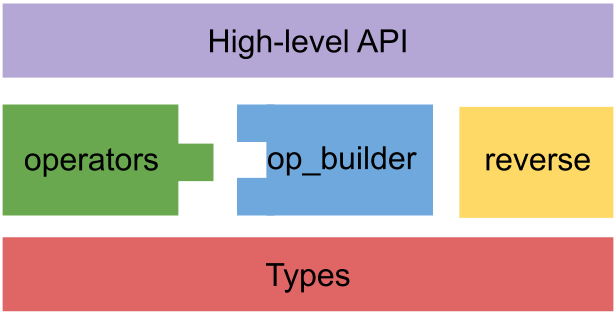

The figure shows the structure of AD module in Owl, and they will be introduced one by one below. Let’s start with the type definition.

type t =

| F of A.elt

| Arr of A.arr

(* primal, tangent, tag *)

| DF of t * t * int

(* primal, adjoint, op, fanout, tag, tracker *)

| DR of t * t ref * op * int ref * int * int ref

and adjoint = t -> t ref -> (t * t) list -> (t * t) list

and register = t list -> t list

and label = string * t list

and op = adjoint * register * label

You will notice some differences. First, besides DF and DR, it also contains two constructors: F and Arr.

This points out one shortcoming of our simple implementation: we cannot process ndarray as input, only float.

That’s why, if you look back at how our computation is constructed, we have to explicitly say that the computation takes two variable as input.

In a real-world application, we only need to pass in a 1x2 vector as input.

You can also note that some extra information fields are included in the DF and DR data types.

The most important one is tag, it is mainly used to solve the problem of high order derivative and nested forward and backward mode. This problem is called perturbation confusion and is important in any AD implementation.

Here we only scratch the surface of this problem.

Think about this: what if we want to compute the derivative of:

i.e. a function that contains another derivative function? It’s simple, since \(\frac{d(x+y)}{dy} = 1\), so \(f'(x) = x' = 1\). Elementary. There is no way we can do it wrong, even with our strawman AD engine, right?

Well, not exactly. Let’s follow our previous simple implementation:

# let diff f x =

match x with

| DF (_, _) ->

f x |> tangent

| DR (_, _, _) ->

let r = f x in

reverse_push [(1., r)];

!(adjoint x)

val diff : (t -> t) -> t -> float = <fun>

# let f x =

let g = diff (fun y -> add_ad x y) in

mul_ad x (make_forward (g (make_forward 2. 1.)) 1.)

val f : t -> t = <fun>

# diff f (make_forward 2. 1.)

- : float = 4.

Hmm, the result is 3 at point \((x=2, y=2)\) but the result should be 1 at any point as we have calculated, so what has gone wrong?

Notice that x=DF(2,1). The tangent value equals to 1, which means that \(\frac{dx}{dx}=1\). Now if we continue to use this same x value in function g, whose variable is y, the same x=DF(2,1) can be translated by the AD engine as \(\frac{dx}{dy}=1\), which is apparently wrong.

Therefore, when used within function g, x should actually be treated as DF(2,0).

The tagging technique is proposed to solve this nested derivative problem. The basic idea is to distinguish derivative calculations and their associated attached values by using a unique tag for each application of the derivative operator.

Now we move on to a higher level. Its structure should be familiar to you now.

The builder module abstract out the general process of forward and reverse modes, while the ops module contains all the specific calculation methods for each operations.

Keep in mind that not all operations can follow exact math rules to perform differentiation. For example, what is the tangent and adjoint of the convolution or concatenation operations? These are all included in the ops.ml.

We have shown how the unary and binary operations can be built by providing two builder modules.

But of course there are many operators that have other type of signatures.

Owl abstracts more operation types according to their number of input variables and output variables.

For example, the qr operations calculates QR decomposition of an input matrix. This operation uses the SIPO (single-input-pair-output) builder template.

In ops, each operation specifies three kinds of functions for calculating the primal value (ff), the tangent value (df), and the adjoint value (dr). However, actually some variants are required.

In our simple examples, all the constants are either DF or DR, and therefore we have to define two different functions f_forward and f_reverse, even though only the definition of constants are different.

Now that the float number is included in the data type t, we can define only one computation function for both modes:

let f_forward x =

let x0, x1 = x in

let v2 = sin_ad x0 in

let v3 = mul_ad x0 x1 in

let v4 = add_ad v2 v3 in

let v5 = F 1. in (* change *)

let v6 = exp_ad v4 in

let v7 = F 1. in (* change *)

let v8 = add_ad v5 v6 in

let v9 = div_ad v7 v8 in

v9

Now, we need to consider the question: how to compute DR and F data types together? To do that, we need to consider more cases in an operation.

For example, in the previous implementation, one multiplication use three functions:

module Mul = struct

let ff a b = Owl_maths.mul a b

let df pa pb ta tb = pa *. tb +. ta *. pb

let dr pa pb a = !a *. pb, !a *. pa

end

But now things get more complicated. For ff a b, we need to consider, e.g. what if a is float and b is an ndarray, or vice versa.

For df and dr, we need to consider what happens if one of the input is constant (F or Arr).

The builder module also has to take these factors into consideration accordingly.

Finally, in the reverse module (Owl_algodiff_reverse), we have the reverse_push functions.

Compared to the simple implementation, it performs an extra shrink step. This step checks adjoint a and its update v, ensuring rank of a must be larger than or equal with rank of v.

Also, the initialisation of the computation is required.

An extra reverse_reset functions is actually required before the reverse propagation begins to reset all adjoint values to the initial zero values.

Above these parts are the high level APIs.

One thing we need to notice is that although diff functions looks straightforward to be implemented using the forward and backward mode, the same cannot be said of other functions, especially jacobian.

Another thing is that, our simple implementation does not support multiple precisions.

It is solved by functors in Owl.

In Algodiff.Generic, all the APIs are encapsulated in a module named Make.

This module takes in an ndarray-like module and generate AD modules with corresponding precision.

If it accepts a Dense.Ndarray.S module, it generate AD modules of single precision; if it is Dense.Ndarray.D passed in, the functor generates AD module that uses double precision.

(To be precise, this description is not quite correct; the required functions actually has to follow the signatures specified in Owl_types_ndarray_algodiff.Sig, which also contains operation about scalar, matrix, and linear algebra, besides ndarray operations.

As we have seen previously, the input modules here are acutally Owl_algodiff_primal_ops.S/D, the wrapper modules for Ndarray.)

Extend AD module

The module design shown above brings one large benefit: it is very flexible in supporting adding new operations on the fly.

Let’s look at an example: suppose the Owl does not provide the operation sin in AD module, and to finish our example, what can we do?

We can use the Builder module in AD.

open Algodiff.D

module Sin = struct

let label = "sin"

let ff_f a = F A.Scalar.(sin a)

let ff_arr a = Arr A.(sin a)

let df _cp ap at = Maths.(at * cos ap)

let dr a _cp ca = Maths.(!ca * cos (primal a))

end

As a user, you need to know how the three types of functions work for the new operation you want to add.

These are defined in a module called Sin here.

This module can be passed as parameters to the builder to build a required operation.

We call it sin_ad to make it different from what the AD module actually provides.

let sin_ad = Builder.build_siso (module Sin : Builder.Siso)

The siso means “single input, single output”.

That’s all! Now we can use this function as if it is a native operation.

You will find that this new operator works seamlessly with existing ones.

# let f x =

let x1 = Mat.get x 0 0 in

let x2 = Mat.get x 0 1 in

Maths.(div (F 1.) (F 1. + exp (x1 * x2 + (sin_ad x1))))

val f : t -> t = <fun>

# let x = Mat.ones 1 2

val x : t = [Arr(1,2)]

# let _ = grad f x |> unpack_arr

- : A.arr =

C0 C1

R0 -0.181974 -0.118142

Lazy Evaluation

Using the Builder enables users to build new operations conveniently, and it greatly improve the clarity of code.

However, with this mechanism comes a new problem: efficiency.

Imagine that a large computation that consists of hundreds and thousands of operations, with a function occurs many times in these operations. (Though not discussed yet, in a neural network which utilises AD, it is quite common to create a large computation where basic functions such as add and mul are repeated tens and hundreds of times.)

With the current Builder approach, every time this operation is used, it has to be created by the builder again. This is apparently not efficient.

We need some mechanism of caching.

This is where the lazy evaluation in OCaml comes to help.

val lazy: 'a -> 'a lazy_t

module Lazy :

sig

type 'a t = 'a lazy_t

val force : 'a t -> 'a

end

As shown in the code above, OCaml provides a built-in function lazy that accept an input of type 'a and returns a 'a lazy_t object.

It is a value of type 'a whose computation has been delayed. This lazy expression won’t be evaluated until it is called by Lazy.force.

The first time it is called by Lazy.force, the expresion is evaluted and the result is saved; and thereafter every time it is called by Lazy.force, the saved results will be returned without evaluation.

Here is an example:

# let x = Printf.printf "hello world!"; 42

hello world!

val x : int = 42

# let lazy_x = lazy (Printf.printf "hello world!"; 42)

val lazy_x : int lazy_t = <lazy>

# let _ = Stdlib.Lazy.force lazy_x

hello world!

- : int = 42

# let _ = Stdlib.Lazy.force lazy_x

- : int = 42

# let _ = Stdlib.Lazy.force lazy_x

- : int = 42

In this example you can see that building lazy_x does not evaluate the content, which is delayed to the first Lazy.force. After that, ever time force is called, only the value is returned; the x itself, including the printf function, will not be evaluated.

We can use this mechanism to improve the implementation of our AD code. Back to our previous section where we need to add a sin operation that the AD module supposedly “does not provide”. We can still do:

open Algodiff.D

module Sin = struct

let label = "sin"

let ff_f a = F A.Scalar.(sin a)

let ff_arr a = Arr A.(sin a)

let df _cp ap at = Maths.(at * cos ap)

let dr a _cp ca = Maths.(!ca * cos (primal a))

end

This part is the same, but now we need to utilise the lazy evaluation:

let _sin_ad = lazy Builder.build_siso (module Sin : Builder.Siso)

let sin_ad = Lazy.force _sin_ad

Int this way, regardless of how many times this sin function is called in a massive computation, the Builder.build_siso process is only invoked once.

What we have talked about is the lazy evaluation at the compiler level, and do not mistake it with another kind of lazy evaluation that are also related with the AD.

Think about that, instead of computing the specific numbers, each step accumulates on a graph, so that computation like primal, tangent, adjoint etc. all generate a graph as result, and evaluation of this graph can only be executed when we think it is suitable.

This leads to delayed lazy evaluation.

Remember that the AD functor takes an ndarray-like module to produce the Algodiff.S or Algodiff.D modules, and to do what we have described, we only need to plugin another ndarray-like module that returns graph instead of numerical value as computation result.

This module is called the computation graph module. It is also a quite important idea, and we will talk about it in detail in the second part of this book.

Summary

In this chapter, we introduce the idea of algorithmic differentiation (AD) and how it works in Owl. First, we start with the classic chain rule in differentiation and different methods to do it, and the benefit of AD. Next, we use an example to introduce two basic modes in AD: the forward mode and the reverse mode. This section is followed by a step-by-step coding of a simple strawman AD engine using OCaml. You can see that the core idea of AD can be implemented with surprisingly simple code. Then we turn to the Owl side: first, how Owl support what we have done in the strawman implementation with the forward and reverse propagation APIs; next, how Owl provides various powerful high level APIs to enable users to directly perform AD. Finally, we give an in-depth introduction to the implementation of the AD module in Owl, including some details that enhance the simple strawman code, how to build user-defined AD computation, and using lazy evaluation to improve performance, etc. Hopefully, after finishing this chapter, you can have a solid understanding of both its theory and implementation.