- Introduction

Introduction

This chapter briefly introduces the outline of the whole book, targeted audience, how to use the book, and then the installation of Owl.

There are different ways to interact with Owl, including utop, notebook, and the Owl-Jupyter. Feel free to choose one as you are exploring the Owl world with us.

What Is Scientific Computing

Scientific Computing is a rapidly evolving multidisciplinary field which uses advanced computing capabilities to understand and solve complex problems. The algorithms used in scientific computing can be generally divided into two types: numerical analysis, and computer algebra (or symbolic computation). The former uses numerical approximation to solve mathematical problems, while the latter requires a exact close-form representation of computation and manipulates symbols that are not assigned specific values.

Both approaches are widely used in various applications fields, such as engineering, physics, biology, finance, etc. Even though these advanced applications are sophisticated, they are all built atop of basic numerical operations in a scientific library, most of which Owl has already provided. For example, you can write a deep neural network with Owl in a few lines of code:

open Owl

open Neural.S

open Neural.S.Graph

open Neural.S.Algodiff

let make_network input_shape =

input input_shape

|> lambda (fun x -> Maths.(x / F 256.))

|> conv2d [|5;5;1;32|] [|1;1|] ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> max_pool2d [|2;2|] [|2;2|]

|> dropout 0.1

|> fully_connected 1024 ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> linear 10 ~act_typ:Activation.(Softmax 1)

|> get_network

It actually consists of basic operations such as add, div, convolution, dot, etc.

It’s totally OK if you have no idea what this piece of code is doing. We’ll cover that later in this book.

The point is that how to dissect a complex application into basic building blocks in a numerical library, and that’s what we are trying to convey throughout this book.

What is Functional Programming

Most existing numerical or scientific computing software are based on the imperative programming paradigm, which uses statements that change a program’s state. Imperative programs often work by being built from one or more procedures, or functions. This modular style is widely adopted. Later around 1980s the idea of object oriented programming is rapidly developed. It extends the modular programming style to include the idea of “object”. An object can contains both data and procedure codes. The imperative programming is not widely adopted in numerical computing for no reason. Almost all computers’ hardware implementation follows imperative design. Actually, FORTRAN, the first cross-platform programming language and an imperative language, is still heavily used for numerical and scientific computations in various fields after first being developed at the 1950s. There is a good chance that, even if you are using modern popular numerical libraries such as SciPy, Julia, or Matlab, they still rely on FORTRAN in the core part somewhere.

As a contrast, the Functional Programming seems to born to perform hight-level tasks. When John McCarthy designed LISP, the first functional programming language, he meant to use it in the artificial intelligence field. The S-expression it uses was meant to be an intermediate representation, but later proved to be powerful and expressive enough. In LISP you can see the clear distinction between functional and imperative programming. Whereas the later uses a sequence of statements to change the state of the program, the former one builds a program that constructs a tree of expressions by using and composing functions.

The fundamental difference between these two programming paradigms lies the underlying model of computation. The imperative one is based on the Alan Turing model. In their book Alan Turing: His Work and Impact, S. Barry Cooper and J. Van Leeuwen said that “computability via Turing machines gave rise to imperative programming”. On the other hand, functional programming evolves from the lambda calculus, a formal system of computation built from function application. Lambda Calculus was invented by Alonzo Church in the 1930s, and it was meant to be a formal mathematical logic systems, instead of programming language. Actually, it was not until the programming language was invented that the relationship between these two is revealed. Turing himself proved that the lambda calculus is Turing complete. (Fun fact: Turing is the student of Church.) We can say that the Lambda calculus is the basis of all functional programming languages.

Compared to imperative programming, functional programming features immutable data, first-class functions, and optimisations on tail-recursion. By using techniques such as higher oder functions, currying, map & reduce etc., functional programming can often achieves parallelisation of threads, lazy evaluation, and determinism of program execution. But asides from these benefits, we are now talking about numerical computation which requires good performance. The question is, do we want to use a functional programming language to do scientific computing? We hope that by presenting Owl, which built on the functional programming language OCaml, we can give you an satisfactory answer.

Who Is This Book For

We really hope this book can cover as broad an audience as possible. Both scientific computing and functional programming are big areas, therefore it is quite a challenge to write a book that satisfies everyone. If you are reading this book now, we assume you are already interested in analytical tasks and enthusiastic about gaining some hands-on experience with functional programming languages. We also assume you know how to program in OCaml and are familiar with the core concepts of functional programming.

We want this book to be relatively general so we have covered many topics in scientific computing. However, this means we cannot dive very deeply into each topic, and each of them per se is probably worth a book. When designing the chapters, we select those topics which are either classical (e.g. statistics, linear algebra) or popular and proven-to-be-effective in industry (e.g. deep neural network, probabilistic programming, etc.). We strive to reach a good balance between breadth and depth. For each topic, we will try our best to list sufficient references to guide our readers to study further.

Unlike other data science books, this book can serve as a reference for other software architects building modern numerical software systems. A significant part of this book is dedicated to explaining the underlying details of Owl. Not only will we give you a bird’s-eye-view of the overall Owl system, but also teach you how to build the system up and optimise each component step-by-step. If you use Owl to build applications, this book can serve as a useful reference manual as well.

Structure of the Book

The book is divided into three parts, and each part focuses on different areas.

Part I first introduces the basics of the Owl system and important conventions to help you in studying how to program with Owl. It then explores various topics in scientific computing, from the classic mathematics, statistics, linear algebra, algorithmic differentiation, optimisation, regression to the popular deep neural network, natural language processing, probabilistic programming, etc. The chapters are loosely organised based on their dependency, e.g. you need to know optimisation before studying regression and deep neural networks.

Part II is dedicated to presenting the architecture of the Owl system. We will dive into each core component and show how we build and optimise the software. By so doing, you will gain a thorough understanding on how a modern numerical system can be structured and developed, and what are the key components needed in such a complex system. Note that even though Owl is developed in OCaml, the knowledge you learnt in this part can be extrapolated to another language.

Part III is a collection of case studies. This part might be the most interesting one for data scientists and practitioners. We will demonstrate how you can build a complete numerical application quickly from scratch using Owl. The cases include computer vision, recommender systems, financial technology, etc.

The book does not enforce any strict order in reading, you can simply jump to the topic that interests you most. If you are completely new to the Owl system, we still strongly recommend you to start with the first two chapters of the book so that you know how to set up a working environment and start programming. All the code snippets included in this book can be compiled with the most recent master branch of Owl, our tooling guarantees the book material stay up-to-date with the software.

Installation

That being said, there is a long way to go from simple math calculation to those large use cases.

Now let’s start from the very first step: installing Owl.

Owl requires OCaml version >=4.10.0. Please make sure you have a working OCaml environment before you start installing Owl. You can read the guide on how to Install OCaml.

Owl’s installation is rather trivial. There are four possible ways as shown below, from the most straightforward one to the least one.

Option 1: Install from OPAM

Thanks to the folks in OCaml Labs, OPAM makes package management in OCaml much easier than before. You can simply type the following the command lines to install.

opam install owl

There is a known issue when installing Owl on ubuntu-based distribution. The reason is that the binary distribution of BLAS and LAPACK are outdated and failed to provide all the interfaces Owl requires. You will need to compile openblas manually, and use the appropriate environment variables to point at your newly compiled library. You can use `owl’s docker files as a reference for this issue.

This way of installation pulls in the most recent Owl released on OPAM. Owl does not have a fixed release schedule. We usually make a new release whenever there are enough changes accumulated or a significant feature implemented. If you want to try the newest development features, we recommend the other ways to install Owl, as below.

Option 2: Pull from Docker Hub

Owl’s docker images are synchronised with the master branch. The image is always automatically built whenever there are new commits. The main version is built with Ubuntu.

You only need to pull the image then start a container.

docker pull matrixanger/owl

docker run -t -i matrixanger/owl

Besides the complete Owl system, the docker image also contains an enhanced OCaml toplevel - utop. You can start utop in the container and try out some examples. The source code of Owl is stored in /root/owl directory. You can modify the source code and rebuild the system directly in the started container.

There are Owl docker images on various Linux distributions. This can be further specified using tags, e.g. docker pull matrixanger/owl:fedora.

Option 3: Pin the Dev-Repo

opam pin allows you to pin the local code to Owl’s development repository on Github. The first command opam depext installs all the dependencies Owl needs.

opam depext owl

opam pin add owl --dev-repo

Option 4: Compile from Source

Compiling directly from the source is an old-school but a recommended option since it enables all the most up-to-date features and patches. First, you need to clone the repository.

git clone git@github.com:owlbarn/owl.git

Second, you need to figure out the missing dependencies and install them.

dune external-lib-deps --missing @install @runtest

Last, this is perhaps the most classic step.

make && make install

If your OPAM is older than V2 beta4, you need one extra step. This is due to a bug in OPAM which copies the compiled library into /.opam/4.06.0/lib/stubslibs rather than /.opam/4.06.0/lib/stublibs. If you don’t want to upgrade OPAM, then you need to manually move dllowl_stubs.so file from stubslib to stublib folder, then everything should work. However, if you have the most recent OPAM installed, this will not be your concern.

CBLAS/LAPACKE Dependency

The most important dependency of Owl is the OpenBLAS library, which efficiently implement the BLAS and LAPACK linear algebra routines.

Linking to the correct OpenBLAS is the key to achieve the best performance. Depending on the specific platform, you can use yum, apt-get, brew to install the binary format. For example on my Mac OSX, the installation looks like this:

brew install homebrew/science/openblas

However, installing from OpenBLAS source code give us extra benefits. First, it implements the most recent interfaces comparing to the outdated binary distribution offered by the native package management tool. Second, it leads to way better performance because OpenBLAS tunes many parameters based on your system configuration and architecture to generate the most optimised binary code.

OpenBLAS already contains an implementation of LAPACKE, as long as you have a Fortran complier installed on your computer, the LAPACKE will be compiled and included in the installation automatically.

Interacting with Owl

There are several ways to interact with Owl system. The classic one is to write an OCaml application, compile the code, link to Owl system, then run it natively on a computer. You can also skip the compilation and linking step, and use Zoo system in Owl to run the code as a script.

However, the easiest way for a beginner to try out Owl is using REPL (Read–Eval–Print Loop), namely an interactive toplevel such as that of Python. The toplevel offers a convenient way to play with small code snippets. The code run in the toplevel is compiled into bytecode rather than native code. Bytecode often runs much slower than native code. However, this has very little impact on Owl’s performance because all its performance-critical functions are implemented in C language.

OCaml code can be compiled in either bytecode or native code. The bytecode is executed on OCaml virtual machine which is less performant then platform-optimised native code. Toplevel runs the user code in bytecode mode, but this has little impact on Owl’s performance because its core functions are implemented in C language. It is hard to notice any performance degradation if you run Owl in a script. In the following, we will introduce two options to set up an interactive environment for Owl.

Using Toplevel

OCaml language has bundled with a simple toplevel, but I recommend utop as a more advance replacement. Installing utop is straightforward using OPAM, simply run the following command in the system shell.

opam install utop

After installation, you can load Owl in utop with the following commands. owl-top is Owl’s toplevel library which will automatically load several related libraries (including owl-zoo, owl-base, and owl core library) to set up a complete numerical environment.

# #require "owl-top"

# open Owl

If you do not want to type these commands every time you start toplevel, you can add them to .ocamlinit file. The toplevel reads .ocamlinit file to initialise the environment during the startup. This file is often stored in the home directory on your computer.

Using Notebook

Jupyter Notebook is a popular way to mix presentation with interactive code execution. It originates from Python world and is widely supported by various languages. One attractive feature of notebook is that it uses client/server architecture and runs in a browser.

If you want to know how to use a notebook and its technical details, please read Jupyter Documentation. Here let me show you how to set up a notebook to run Owl step by step.

Run the following commands in the shell will install all the dependency for you. This includes Jupyter Notebook and its OCaml language extension.

pip install jupyter

opam install jupyter

jupyter kernelspec install --name ocaml-jupyter "$(opam config var share)/jupyter"

To start a Jupyter notebook, you can run this command. The command starts a local server running on http://127.0.0.1:8888/, then opens a tab in your browser as the client.

jupyter notebook

If you wish to run a notebook server remotely, please refer to “Running a notebook server” for more information. To set up a server for multiple users, which is especially useful for educational purpose, please consult to JupyterHub system.

When everything is up and running, you can start a new notebook in the web interface. In the new notebook, you must run the following OCaml code in the first input field to load Owl environment.

# #use "topfind"

# #require "owl-top, jupyter.notebook"

At this point, a complete Owl environment is set up in the Jupyter Notebook, and you are free to go with any experiments you like. For example, you can simply copy & paste the whole lazy_mnist.ml to train a convolutional neural network in the notebook. But here, let us just use the following code.

# #use "topfind"

# #require "owl-top, jupyter.notebook"

# open Owl

# open Neural.S

# open Neural.S.Graph

# open Neural.S.Algodiff

# let make_network input_shape =

input input_shape

|> lambda (fun x -> Maths.(x / F 256.))

|> conv2d [|5;5;1;32|] [|1;1|] ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> max_pool2d [|2;2|] [|2;2|]

|> dropout 0.1

|> fully_connected 1024 ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> linear 10 ~act_typ:Activation.(Softmax 1)

|> get_network

val make_network : int array -> network = <fun>

The make_network function defines the structure of a convolution neural network. By passing the shape of input data, Owl automatically infers the shape of whole network, and prints out the summary of network structure nicely on the screen.

# make_network [|28;28;1|]

- : network =

18839

[ Node input_0 ]:

Input : in/out:[*,28,28,1]

prev:[] next:[lambda_1]

[ Node lambda_1 ]:

Lambda : in:[*,28,28,1] out:[*,28,28,1]

customised f : t -> t

prev:[input_0] next:[conv2d_2]

[ Node conv2d_2 ]:

Conv2D : tensor in:[*;28,28,1] out:[*,28,28,32]

init : tanh

params : 832

kernel : 5 x 5 x 1 x 32

b : 32

stride : [1; 1]

prev:[lambda_1] next:[activation_3]

[ Node activation_3 ]:

Activation : relu in/out:[*,28,28,32]

prev:[conv2d_2] next:[maxpool2d_4]

[ Node maxpool2d_4 ]:

MaxPool2D : tensor in:[*,28,28,32] out:[*,14,14,32]

padding : SAME

kernel : [2; 2]

stride : [2; 2]

prev:[activation_3] next:[dropout_5]

[ Node dropout_5 ]:

Dropout : in:[*,14,14,32] out:[*,14,14,32]

rate : 0.1

prev:[maxpool2d_4] next:[fullyconnected_6]

[ Node fullyconnected_6 ]:

FullyConnected : tensor in:[*,14,14,32] matrix out:(*,1024)

init : standard

params : 6423552

w : 6272 x 1024

b : 1 x 1024

prev:[dropout_5] next:[activation_7]

[ Node activation_7 ]:

Activation : relu in/out:[*,1024]

prev:[fullyconnected_6] next:[linear_8]

[ Node linear_8 ]:

Linear : matrix in:(*,1024) out:(*,10)

init : standard

params : 10250

w : 1024 x 10

b : 1 x 10

prev:[activation_7] next:[activation_9]

[ Node activation_9 ]:

Activation : softmax 1 in/out:[*,10]

prev:[linear_8] next:[]

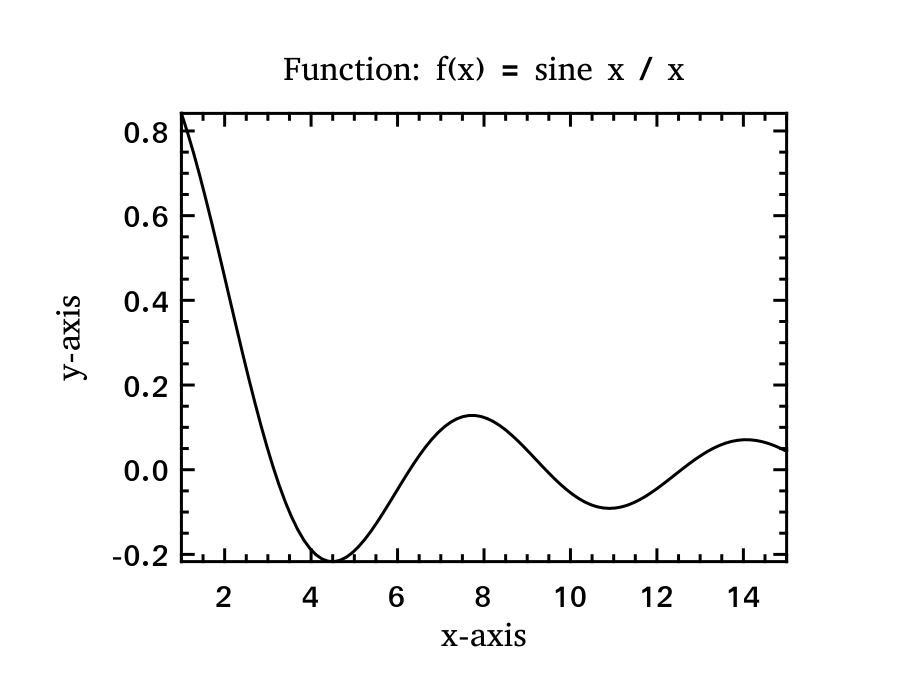

The Second example demonstrates how to plot figures in notebook. Because Owl’s Plot module does not support in-memory plotting, the figure needs to be written into a file first before passing to Jupyter_notebook.display_file to render.

# #use "topfind"

# #require "owl-top, owl-plplot, jupyter.notebook"

# open Owl

# open Owl_plplot

# let f x = Maths.sin x /. x in

let h = Plot.create "plot_00.png" in

Plot.set_title h "Function: f(x) = sine x / x";

Plot.set_xlabel h "x-axis";

Plot.set_ylabel h "y-axis";

Plot.set_font_size h 8.;

Plot.set_pen_size h 3.;

Plot.plot_fun ~h f 1. 15.;

Plot.output h

- : unit = ()

To load the image into browser, we need to call the Jupyter_notebook.display_file function. Then we can see the plot [@fig:introduction:example00] is correctly rendered in the notebook running in your browser. Plotting capability greatly enriches the content of an interactive presentation.

Jupyter_notebook.display_file ~base64:true "image/png" "plot_00.png"

Even though the extra call to display_file is not ideal, it is obvious that the tooling in OCaml ecosystem has been moving forward quickly. I believe we will soon have even better and more convenient tools for interactive data analytical applications.

Using Owl-Jupyter

For the time being, if you want to save that extra line to display a image in Jupyter. There is a convenient module called owl-jupyter. Owl-jupyter module overloads the original Plot.output function so that a plotted figure can be directly shown on the page.

# #use "topfind"

# #require "owl-jupyter"

# open Owl_jupyter

# let f x = Maths.sin x /. x in

let h = Plot.create "plot_01.png" in

Plot.set_title h "Function: f(x) = sine x / x";

Plot.set_xlabel h "x-axis";

Plot.set_ylabel h "y-axis";

Plot.set_font_size h 8.;

Plot.set_pen_size h 3.;

Plot.plot_fun ~h f 1. 15.;

Plot.output h

- : unit = ()

From the example above, you can see Owl users’ experience can be significantly improved by using the notebook.