- Deep Neural Networks

Deep Neural Networks

The Neural Network has been a hot research topic and widely used in engineering and social life. The name “neural network” and its original idea comes from modelling how (the computer scientists think) the biological neural systems work. The signal processing in neurons are modelled as computation, and the complex transmission and triggering of impulses are simplified as activations, etc.

Since the inception of this idea in about 1940’s, the neural network has been revised and achieved astounding result. In this chapter, we will first explain that, as complex as it seems, the neural network is nothing more than a step forward based on the regression we have introduced. Then we will present the neural network module, including how to use it and how this module is designed and built based on existing mechanisms such as Algorithmic Differentiation and Optimisation. After the basic feedforward neural network and the Owl module, we then proceed to introduce some more advanced type of neural networks, including the Convolutional Neural Network, the Recurrent Neural Network, and Generative Adversarial Network. Let’s begin.

Perceptron

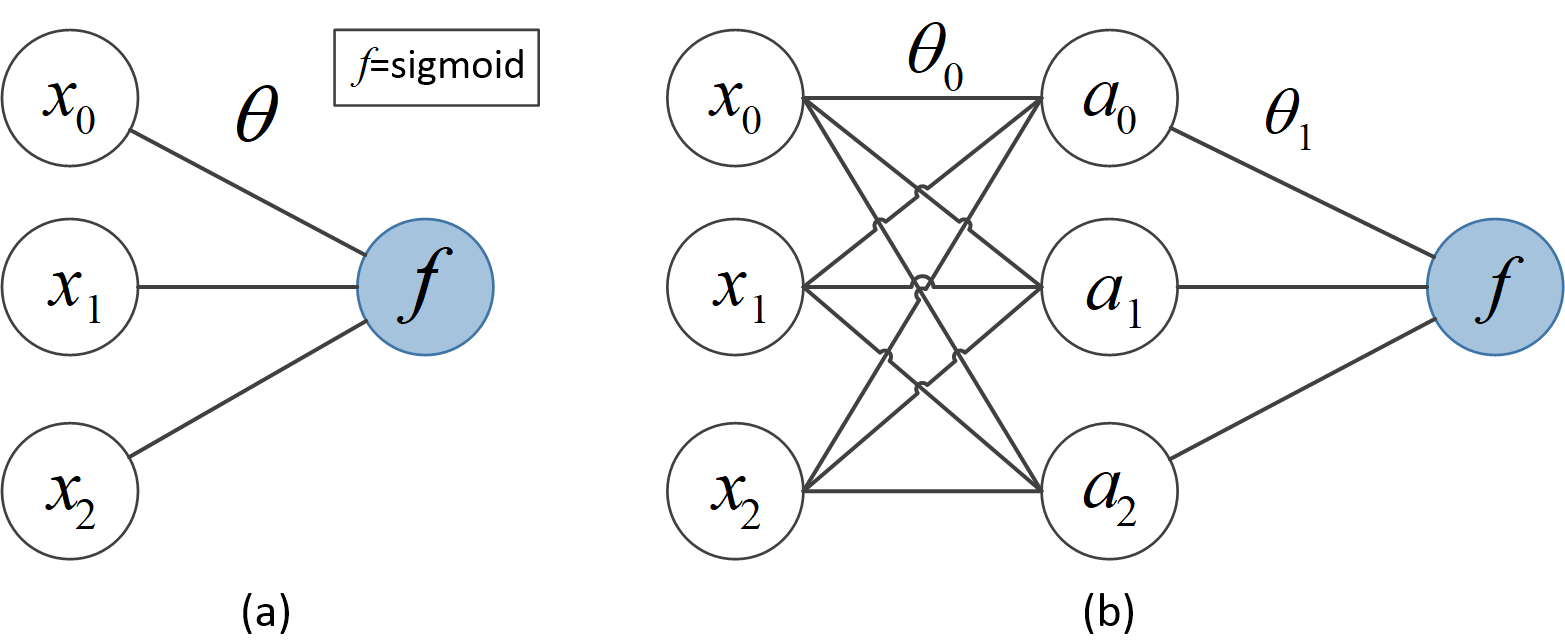

Before diving into the complex neural network structures, let’s briefly recount where everything begins: the perceptron. The definition is actually very similar to that of logistic regression. Remember that logistic regression can be expressed as:

\[h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(x) = g(x^T~\boldsymbol{\theta}),\]where the \(g\) function is a sigmoid function: \(g(x) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-x}}\). This function projects a number in \([-\infty, \infty]\) to \([0, 1]\). To get a perceptron, all we need to do is to change the function to:

\[g(x)= \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \mathbf{w \cdot x + b > 0}\\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]This function is called a Unit Step Function, or heaviside/binary step function. Instead of a range \([0, 1]\), the result can only be either 0 or 1. It is thus suitable for binary classification. In the perceptron learning algorithm, we can still follow the previous parameter update method:

\[\theta_i = \theta_i - \lambda~(y - h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}))x_i\]for each pair of training data x and y.

The perceptron was first proposed in 1950’s to perform binary image classification. Back then it was thought to model how individual neuron in the brain works. Though initially deemed promising, people quickly realise that perceptrons could not be trained to recognise many classes of patterns, which is almost the case in image recognition. To fix this problem requires introducing more layers of interconnected perceptrons. That is called feedforward neural network, and we will talk about it in detail in the two sections below.

Yet Another Regression

To some extent, a deep neural network is nothing but a regression problem in a very high-dimensional space. We need to minimise its cost function by utilising higher-order derivatives. Before looking into the actual Neural module, let’s build a small neural network from scratch.

Following the previous logistic regression, in this section we build a simple neural network with a hidden layer, and train its parameters. The task is hand-written recognition. The starting example is also inspired by the Machine Learning course by Andrew Ng.

Model Representation

In logistic regression we have multiple parameters as one layer to decide if the input data belongs to one type or the other. Now we need to extend it towards multiple classes, with a new hidden layer.

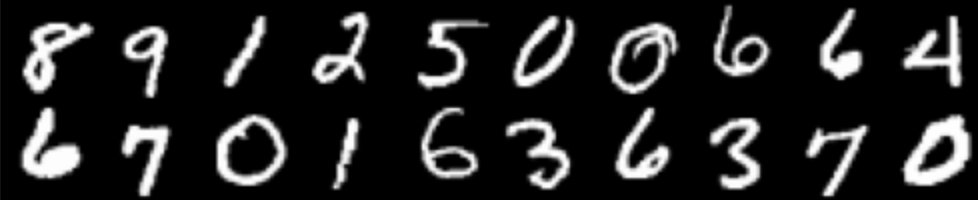

The data we will use is from MNIST dataset. You can use Owl.Dataset.download_all() to download the dataset.

let x, _, y = Dataset.load_mnist_train_data_arr ()

# let x_shape, y_shape =

Dense.Ndarray.S.shape x, Dense.Ndarray.S.shape y

val x_shape : int array = [|60000; 28; 28; 1|]

val y_shape : int array = [|60000; 10|]

The label is in the one-hot format:

val y : Owl_dense_matrix.S.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9

R0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

R1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

R2 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

It shows the first three labels are 5, 0, and 4.

Forward Propagation

Specifically we use a hidden layer of size 25, and the output class is 10. Since we will use derivatives in training parameters, we construct all the computation using the Algorithmic Differentiation module. The computation is repeated logistic regression:

\[h_{\Theta}(x) = f(f(x^T~\boldsymbol{\theta_0})~\boldsymbol{\theta_1}).\]Here \(\Theta\) denotes the collection of parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta_0}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\theta_1}\). It can be implemented as:

open Algodiff.D

module N = Dense.Ndarray.D

let input_size = 28 * 28

let hidden_size = 25

let classes = 10

let theta0 = Arr (N.uniform [|input_size; hidden_size|])

let theta1 = Arr (N.uniform [|hidden_size; classes|])

let h theta0 theta1 x =

let t = Arr.dot x theta0 |> Maths.sigmoid in

Arr.dot t theta1 |> Maths.sigmoid

That’s it. We can now classify an input 28x28 array into one of the ten classes… except that we can’t.

Currently we only use random content as the parameters.

We need to train the model and find suitable \(\theta_0\) and \(\theta_1\) parameters.

Back propagation

Training a network is essentially a process of minimising the cost function by adjusting the weight of each layer. The core of training is the backpropagation algorithm. As its name suggests, backpropagation algorithm propagates the error from the end of a network back to the input layer, in the reverse direction of evaluating the network. Backpropagation algorithm is especially useful for those functions whose input parameters are far larger than output parameters.

Backpropagation is the core of all neural networks; actually it is just a special case of reverse mode AD. Therefore, we can write up the backpropagation algorithm from scratch easily with the help of Algodiff module.

Recall in the Regression chapter, training parameters is the process is to find the parameters that minimise the cost function of iteratively. In the case of this neural network, its cost function \(J\) is similar to that of logistic regression. Suppose we have \(m\) training data pairs, then it can be expressed as:

\[J_{\Theta}(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) = \frac{1}{m}\sum_{i=1}^m(-y^{(i)}log(h_\Theta(x^{(i)}))-(1 -y^{(i)})log(1-h_\Theta(x^{(i)}))).\]It can be translated to Owl code as:

let j t0 t1 x y =

let z = h t0 t1 x in

Maths.add

(Maths.cross_entropy y z)

(Maths.cross_entropy Arr.(sub (ones (shape y)) y)

Arr.(sub (ones (shape z)) z))

Here the “cross_entropy y x” means \(-y~\log(x)\).

In the regression chapter, to find the suitable parameters that minimise \(J\), we iteratively apply:

\[\theta_j \leftarrow \theta_j - \alpha~\frac{\partial J}{\partial \theta_j}\]until it converges. The same also applies here. But the partial derivative is not intuitive to give an analytical solution. But actually we don’t have to now that we are using the AD module. The partial derivatives of both parameters can be correctly calculated. We have shown in the Algorithmic Differentiation chapter how it can be done in Owl:

let x', y' = Dataset.draw_samples x y 1

let cost = j t0 t1 (Arr x') (Arr y')

let _ = reverse_prop (F 1.) cost

let theta0' = adjval t0 |> unpack_arr

let theta1' = adjval t1 |> unpack_arr

That’s it for one iteration. We get \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \theta_j}\), and then can iteratively update the \(\theta_0\) and \(\theta_1\) parameters.

Feed Forward Network

This example works well, but nevertheless has several problems. In the next step, we revise it to add more details.

Layers

First, the previous example mixes all the computation together. We need to add the abstraction of layer as the building block of neural network instead of numerous basic computations. The following code defines the layer and network type, both are OCaml record types.

Also note that for each layer, besides the matrix multiplication, we also added an extra bias parameter. The bias vector influences the output without actually interacting with the data. Each linear layer performs the following calculation where \(a\) is a non-linear activation function.

\[y = a(x \times w + b)\]Each layer consists of three components: weight w, bias b, and activation function a. A network is just a collection of layers.

open Algodiff.S

type layer = {

mutable w : t;

mutable b : t;

mutable a : t -> t;

}

type network = { layers : layer array }

Despite of the complicated internal structure, we can treat a neural network as a function, which is takes input data and generates predictions. The question is how to evaluate a network. Evaluating a network can be decomposed as a sequence of evaluation of layers.

The output of one layer will be given to the next layer as its input, moving forward until it reaches the end. The following two lines show how to evaluate a neural network in the forward mode.

let run_layer x l = Maths.((x *@ l.w) + l.b) |> l.a

let run_network x nn = Array.fold_left run_layer x nn.layers

The run_network can generate what equals to the \(h_\Theta(x)\) function in the previous section.

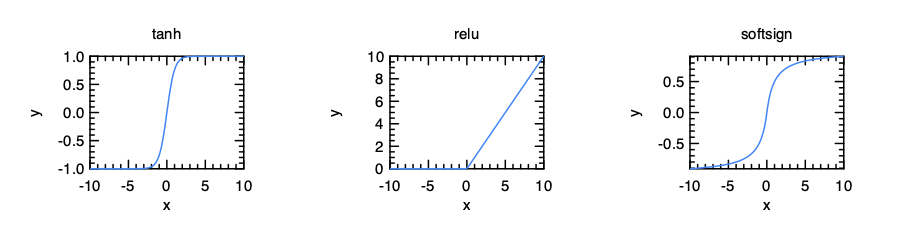

Activation Functions

Let’s step back and check again the similarity between neural network and what we think biological neuron works. So far we have seen how to connect every node (or “neuron”) to every node between two layers. That’s hardly how the real neuron works. Instead of activating all the connecting neurons during information transformation, different neurons are electrically activated differently in a kind of irregular fashion.

Biology aside, think about it in the mathematical way: if we keep fully connect multiple layers, that’s in essence multiple matrix multiplication, and that would equals to only one single matrix multiplication.

Therefore, to make adding more layers mean something, we frequently use the activation functions to simulate how neuron works in biology and introduce non-linearity into the network. Non-linearity is a property we are looking for in neural network, since most real world data demonstrate non-linear features. If it is linear, then we human can often simply observe it and use something like linear regression to find the solution.

Actually we have already seen two types of activation function so far.

The first is the Unit Step Function.

It works like a simple on/off digital gate that allows part of neurons to be activated.

Then there is the familiar sigmoid function. It limits the value to be within 0 and 1, and therefore we can think of it as a kind of probability of being activated.

Besides these two, there are many other types of non-linear activation functions.

The tanh(x) function computes \(\frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{e^x + e^{-x}}\).

Softsign computes \(\frac{x}{1+|x|}\).

The relu(x) computes:

And there is the softmax function.

It takes a vector of \(K\) real numbers, and normalizes it into a probability distribution consisting of \(K\) probabilities proportional to the exponentials of the input numbers:

We will keep using these activation functions in later network structures.

Initialisation

In this small example, we will only use two layers, l0 and l1.

l0 uses a 784 x 40 matrix as weight, and tanh as activation function.

l1 is the output layer and softmax is the cost function.

let l0 = {

w = Maths.(Mat.uniform 784 40 * F 0.15 - F 0.075);

b = Mat.zeros 1 40;

a = Maths.tanh;

}

let l1 = {

w = Maths.(Mat.uniform 40 10 * F 0.15 - F 0.075);

b = Mat.zeros 1 10;

a = Maths.softmax ~axis:1;

}

let nn = {layers = [|l0; l1|]}

This definition is plain to see, but there is still one thing to say: the initialisation of parameters. From the regression chapter we have seen that how finding a good initial starting point can be beneficial to the performance of gradient descent. You might be thinking that uniformly generated parameters should work fine, but that’s not the case.

Now we know that the essence of a layer is basically a matrix multiplication.

If we use randomly initialise the parameter using uniform or normal distribution, you will find out that the results will soon explode after several layers.

Even if by using sigmoid activation function we can control the number within [0, 1], that still means the results are very near to 1, and the gradient will be extremely small.

On the other hand, if we choose initial parameters that are close to 0, then the output result from the network itself would be close zero.

It is call the “vanishing gradient” problem, and in both cases, the network cannot learn well.

There are many works that aim to solve this problem.

One common solution is to use ReLU as activation functions since it is more robust to this issue.

As to initialisation itself, there are multiple heuristics that can be used.

For example, the commonly used Xavier initialization approach proposes to scale the uniformly generated parameters with: \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}}\).

This parameter is shared by two layers, and \(n\) is the size the first layer.

This approach is especially suitable to use with tanh activation function.

It is provided by the Init.Standard method in the initialisation module.

The Init.LecunNormal is similar, but it uses \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}}\) as the standard deviation of the Gaussian random generator.

If we want to use the uniformly generation approach, then the parameters should be scaled by \(\sqrt{\frac{6}{n_0 + n_1}}\). For this method we use Init.GlorotUniform or Init.Tanh.

Of course, besides these methods, we still provide the mechanism to use the vanilla uniform (Init.Uniform) or gaussian (Init.Gaussian) randomisation, or a custom method (Init.Custom).

Training

The loss function is constructed in the same way.

let loss_fun nn x y =

let t = tag () in

Array.iter (fun l ->

l.w <- make_reverse l.w t;

l.b <- make_reverse l.b t;

) nn.layers;

Maths.(cross_entropy y (run_network x nn) / (F (Mat.row_num y |> float_of_int)))

The backprop also uses the same procedure as the previous example.

The partial derivative is gotten using adjval, and the parameter w and b of each layer are updated accordingly.

It then uses the gradient descent method, and the learning rate eta is fixed.

let backprop nn eta x y =

let loss = loss_fun nn x y in

reverse_prop (F 1.) loss;

Array.iter (fun l ->

l.w <- Maths.((primal l.w) - (eta * (adjval l.w))) |> primal;

l.b <- Maths.((primal l.b) - (eta * (adjval l.b))) |> primal;

) nn.layers;

loss |> unpack_flt

Test

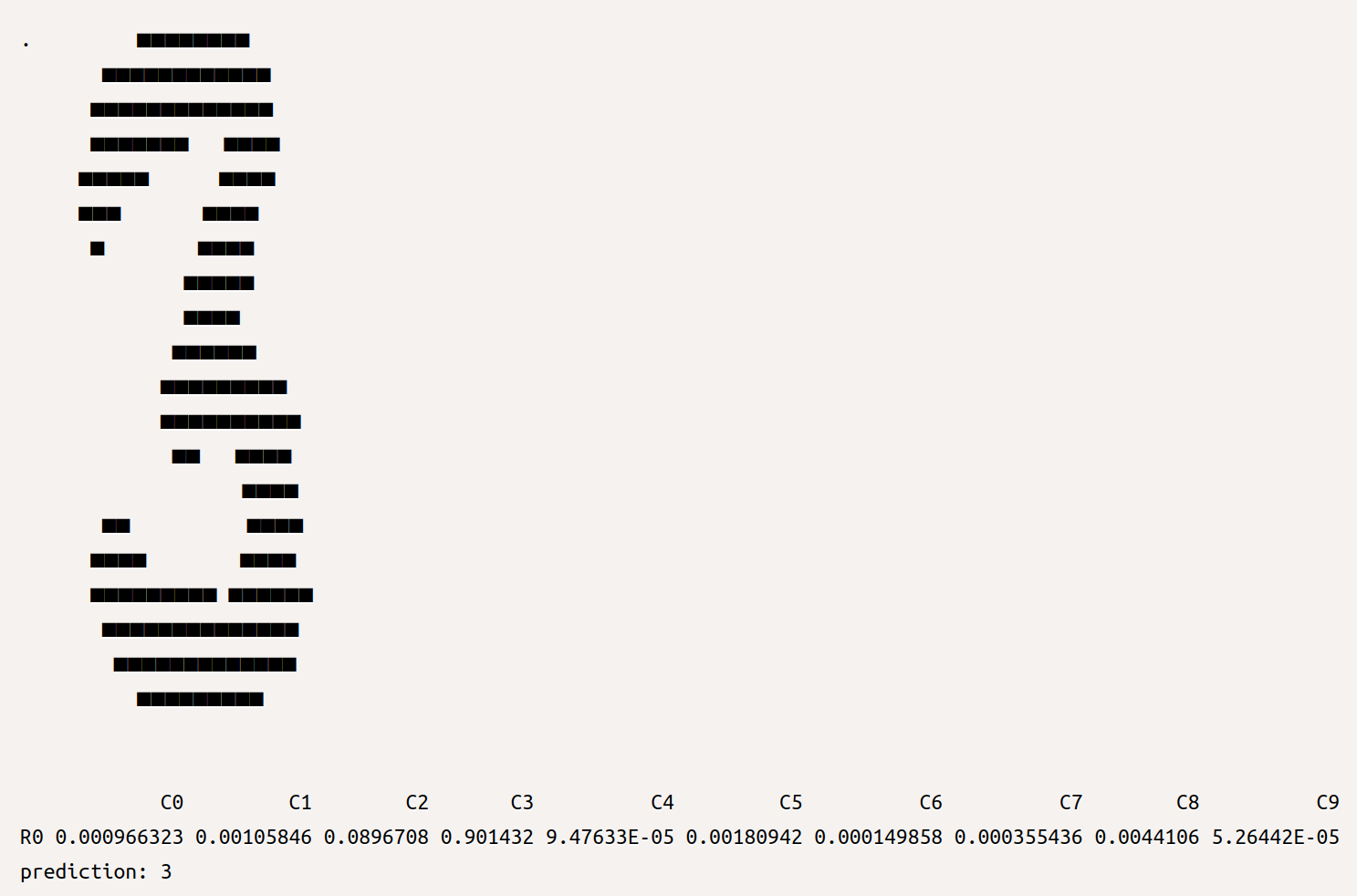

We need to see how well our trained model works.

The test function performs model inference and compares the predictions with the labelled data. By doing so, we can evaluate the accuracy of a neural network.

let test nn x y =

Dense.Matrix.S.iter2_rows (fun u v ->

let p = run_network (Arr u) nn |> unpack_arr in

Dense.Matrix.Generic.print p;

Printf.printf "prediction: %i\n" (let _, i = Dense.Matrix.Generic.max_i p in i.(1))

) (unpack_arr x) (unpack_arr y)

Finally, we can put all the previous parts together. The following code starts the training for 999 iterations.

let main () =

let x, _, y = Dataset.load_mnist_train_data () in

for i = 1 to 999 do

let x', y' = Dataset.draw_samples x y 100 in

backprop nn (F 0.01) (Arr x') (Arr y')

|> Owl_log.info "#%03i : loss = %g" i

done;

let x, y, _ = Dataset.load_mnist_test_data () in

let x, y = Dataset.draw_samples x y 10 in

test nn (Arr x) (Arr y)

When the training starts, our application keeps printing the value of loss function at the end of iteration. From the output, we can see the value of loss function keeps decreasing quickly after training starts.

2019-11-12 01:04:14.632 INFO : #001 : loss = 2.54432

2019-11-12 01:04:14.645 INFO : #002 : loss = 2.48446

2019-11-12 01:04:14.684 INFO : #003 : loss = 2.33889

2019-11-12 01:04:14.696 INFO : #004 : loss = 2.28728

2019-11-12 01:04:14.709 INFO : #005 : loss = 2.23134

2019-11-12 01:04:14.720 INFO : #006 : loss = 2.21974

2019-11-12 01:04:14.730 INFO : #007 : loss = 2.0249

2019-11-12 01:04:14.740 INFO : #008 : loss = 1.96638

After the training is finished, we test the accuracy of the network. Here is one example where we input hand-written 3. The vector below shows the prediction. The model says with \(90.14%\) chance it is a number 3, which is quite accurate.

{ width=60% #fig:neural-network:plot01 }

{ width=60% #fig:neural-network:plot01 }

Neural Network Module

The simple implementation looks promising enough, but we cannot really leave it for the users to define layers, networks, and the training procedure all by themselves. That would hard be a scalable approach. Therefore, now is finally the time to introduce the Neural Network module provided by Owl. It is actually very similar to the naive framework we just built, but with more complete support to various neurons.

Module Structure

First thing first: a bit of history about neural network module in Owl. Owl has always been designed as a general-purpose numerical library, and we never planned to make it yet another framework for deep neural networks. The original motivation of including such a neural network module was simply for demo purpose, since in almost every presentation we had been to, there was always the same question from the audience: “can Owl do deep neural network by the way?” In the end, we became curious about this question ourselves, although the perspective was slightly different. We were sure we could implement a proper neural network framework atop of Owl, but we didn’t know how easy it is. We take it as an excellent opportunity to test Owl’s capability and expressiveness in developing complicated analytical applications.

The outcome is wonderful. It turns out with Owl’s architecture and its internal functionality (algodiff, optimisation, etc.), combined with OCaml’s powerful module system, implementing a full featured neural network module only requires approximately 3500 LOC. Yes, you heard me, 3500 LOC, and it reach TensorFlow’s level of performance on CPU (by the time we measured in 2018).

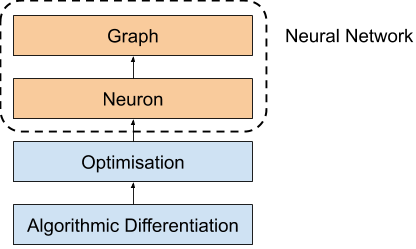

To understand how we do that, let’s look at the figure above.

It shows the basic module architecture of the neural network module.

The neural network in Owl mainly consists of two sub modules: Neuron and Graph.

In the module system, they are built based on the Optimisation module, which are in turn based on the Algorithmic Differentiation module (Algodiff).

Algodiff is the most powerful part of Owl and offers great benefits to the modules built atop of it.

In neural network case, we only need to describe the logic of the forward pass without worrying about the backward propagation at all, because the Algodiff figures it out automatically for us thus reduces the potential errors. This explains why a full-featured neural network module only requires less than 3.5k lines of code. Actually, if you are really interested, you can have a look at Owl’s Feedforward Network which only uses a couple of hundreds lines of code to implement a complete Feedforward network.

We have already introduced the Algodiff module in Owl in previous chapter.

Neurons

The basic unit in neural network is Neuron.

We have implemented a set of commonly used neurons in Owl.Neural.Neuron. Each neuron is a standalone module.

We have encapsulated the computation introduced above into a neuron.

In previous chapter we have seen how the input and hidden layer can be connected, and we abstract it into the FullyConnected layer.

We take this neuron as an example.

module FullyConnected = struct

type neuron_typ =

{ mutable w : t;

mutable b : t;

mutable init_typ : Init.typ;

mutable in_shape : int array;

mutable out_shape : int array

}

...

end

This module contains the two parameters we have seen: w and b, both of type t which means the Algodiff array.

Besides, we also need to specify the input and output shape. They are actually the length of input vector and the length of the hidden layer itself.

The last part in the definition of this neuron init_typ is about what kind of initialisation we use, as has been discussed before.

Then this module contains several standard functions that are shared by all the neuron modules.

let create ?inputs o init_typ =

let in_shape =

match inputs with

| Some i -> [| i |]

| None -> [| 0 |]

in

{ w = Mat.empty 0 o; b = Mat.empty 1 o; init_typ; in_shape; out_shape = [| o |] }

After definition of its type, a neuron is created using the create function.

Here we only need to specify the output shape, or the size of hidden layer o.

let connect out_shape l =

assert (Array.length out_shape > 0);

l.in_shape <- Array.copy out_shape

The input shape is actually taken from the previous layer in the connect function.

We will see why we need this function later.

Next we initialise the parameters accordingly:

let init l =

let m = Array.fold_left (fun a b -> a * b) 1 l.in_shape in

let n = l.out_shape.(0) in

l.w <- Init.run l.init_typ [| m; n |] l.w;

l.b <- Mat.zeros 1 n

There is nothing magical in the init function. The m is a flattened input size in case input ndarray is of multiple dimensions.

The w parameter is initialised with predefined initialisation function, and we can just make b all zero, which means no bias at the beginning.

Then we have the forward propagation part, in the run function:

let run x l =

let m = Mat.row_num l.w in

let n = Arr.numel x / m in

let x = Maths.reshape x [| n; m |] in

let y = Maths.((x *@ l.w) + l.b) in

y

It’s the familiar matrix multiplication and summation we have shown previously. The only thing we add is to reshape the possible multiple dimension input into a matrix.

Finally, we divide the backpropagation into several parts: tagging the parameters, get the derivatives, and update parameters. They are also included in the neuron module:

let mktag t l =

l.w <- make_reverse l.w t;

l.b <- make_reverse l.b t

let mkpri l = [| primal l.w; primal l.b |]

let mkadj l = [| adjval l.w; adjval l.b |]

let update l u =

l.w <- u.(0) |> primal';

l.b <- u.(1) |> primal'

That’s about the main part of the FullyConnected neuron and the other similar neurons.

Adding a new type of neuron is quite easy thanks to Owl’s Algodiff module.

As other modules such as Ndarray and Algodiff, the Owl.Neural provides two submodules S and D for both single precision and double precision neural networks.

Neural Graph

Neuron is the core of the neural network module, but we cannot work directly on the neurons.

In a neural network, the individual neuron has to be instantiated into a node and constructed into a graph.

And it’s the Graph module we users have access to.

The node in a neural network is defined as:

type node = {

mutable name : string;

mutable prev : node array;

mutable next : node array

mutable neuron : neuron

mutable output : t option

mutable network : network

mutable train : bool

}

Besides the neuron itself, a node also contains information such as its parents, children, output, the network this node belongs to, a flag if this node is only for training, etc.

In the Graph module, most of the time we need to deal with functions that build node and connect it to existing network. For example:

let fully_connected ?name ?(init_typ = Init.Standard) outputs input_node =

let neuron = FullyConnected (FullyConnected.create outputs init_typ) in

let nn = get_network input_node in

let n = make_node ?name [||] [||] neuron None nn in

add_node nn [| input_node |] n

What this function does is simple: instantiate the FullyConnected neuron using its create function, and wrap it into a node n.

The current network nn is found from its input node input_node.

Then we add n as a child node to nn and connect it to its parents using the add_node function.

This step uses the connect function of the neuron, and also update the child’s input and output shape during connection.

Finally, after understanding the Graph module of Owl, we can now “officially” re-define the network in previous example with the Owl neural network module:

open Neural.S

open Neural.S.Graph

open Neural.S.Algodiff

let make_network () =

input [|28; 28; 1|]

|> fully_connected 40 ~act_typ:Activation.Tanh

|> linear 10 ~act_typ:Activation.(Softmax 1)

|> get_network

We can see how the input, the hidden layer, and the output from previous example are concisely expressed using the Owl neural network graph API.

The linear is similar to fully_connected, only that it accepts one-dimensional input.

The parameter act_typ specifies the activation function applied on the output of this node.

Usually, the network definition always starts with input neuron and ends with get_network function which finalises and returns the constructed network. We can also see the input shape is reserved as a passed in parameter so the shape of the data and the parameters will be inferred later whenever the input_shape is determined.

Owl provides a convenient way to construct neural networks. You only need to provide the shape of the data in the first node (often input neuron), then Owl will automatically infer the shape for you in the downstream nodes which save us a lot of efforts and significantly reduces the potential bugs.

Training Parameters

Now the last thing to do is to train the model.

Again, we want to encapsulate all the manual back-propagation and parameter update into one simple function.

It is mainly implemented in the minimise_network function in the Optimise module.

This module provides the Params submodule which maintains a set of training hyper-parameters.

Without getting into the sea of implementation details, we focus on one single \(i\)-th update iteration and see how these hyper-parameters work.

Let’s start with the first step in this iteration: training data bataching.

let xt, yt = bach_fun x y i

In parameters we can use Batch module to specify how the training data are batched.

In the definition of cost functions, we often assume that to update the parameters, we need to include all the data.

This approach is Batch.Full.

However, for large scale training task, there can be millions of training data.

Besides the memory issue, it is also a waste to wait for all the data to be processed to get an updated parameter.

The mostly commonly used batching method is mini-batch (Batch.Mini).

It only takes a small part of the training data.

As long as the data is fully covered after certain number of iterations, this approach is mathematically equivalent to the full batch.

Actually this method is usually more efficient since the training data are often correlated.

You don’t need to cover all the training data to train a good model.

For example, if the model have seen 10 cat images in training, then probably it does not need to be trained on another 10 cat images to get a fairly good model to recognise cat.

To move this method to extreme where only one data sample is used every time, we get the stochastic batch (Batch.Stochastic) method.

It is often not a very good choice, since the vectorised computation optimisation will then not be efficiently utilised.

Another batching approach is Batch.Sample. It is the same as mini batch, except that every mini batch is randomly chosen from the training data.

It is especially important for the data that are “in order”.

Imagine that in the MNIST task, all the training data are ordered according to the digit value.

In that case, you may have a model that only works for the lower digits like 0, 1, and 2 at the beginning.

let yt', ws = forward xt

There is nothing magical about the forward function.

It executes the computation layer by layer, and accumulates the result in yt'.

Note that yt' is not simply an ndarray, but an Algodiff data type that contains all the computation graph information.

The ws is an array of all the parameters in the neural network.

let loss = loss_fun yt yt'

let loss = Maths.(loss / _f (Mat.row_num yt |> float_of_int))

To compare how different the inference result y' is from the true label y, we need the loss function.

Previously we have used the cross_entropy, and in the Loss module, the optimisation module provides other popular loss function:

Loss.L1norm: \(\sum\|y - y'\|\)Loss.L2norm: \(\sum\|y - y'\|_2\)Loss.Quadratic: \(\sum\|y - y'\|_2^2\)Loss.Hinge: \(\sum\textrm{max}(0, 1-y^Ty')\)

let reg =

match params.regularisation <> Regularisation.None with

| true -> Owl_utils.aarr_fold (fun a w -> Maths.(a + regl_fun w)) (_f 0.) ws

| false -> _f 0.

let loss = Maths.(loss + reg)

In the regression chapter we have talked about the idea of regularisation and its benefit.

We have also introduced different types of regularisation methods.

In the optimisation module, we can use Regularisation.L1norm, Regularisation.L2norm, or Regularisation.Elastic_net in training.

We can also choose not to apply regularisation method by using the None parameter.

In the Graph module, Owl provides a train function that is a wrapper of this optimisation function.

As a result, we can train the network by simply calling:

let train () =

let x, _, y = Dataset.load_mnist_train_data_arr () in

let network = make_network () in

let params = Params.config

~batch:(Batch.Mini 100)

~learning_rate:(Learning_Rate.Adagrad 0.005) 0.1

in

Graph.train ~params network x y |> ignore;

network

The Adagrad part may seem unfamiliar.

So far we keep using a constant learning rate (Learning_rate.Const), but the problem is that, this is hardly an ideal setting.

We want the gradient descent to be fast with large step at the beginning, but we also want it to be in small steps when it reaches the minimum point.

Therefore, Owl provides the Decay and Exp_decay learning rate methods; both method reduce the base learning rate according to the iteration.

The first reduces the learning rate by a factor of \(\frac{1}{1+ik}\), where \(i\) is the iteration number and \(k\) is the reduction rate.

Similarly, the second method reduces the leaning rate by a factor of \(e^{-ik}\).

We also implement the other more advanced learning methods.

The Adagrad we use here adapts the learning rate to the parameters, not just iteration number. It uses smaller step for parameters associated with frequently occurring features. Therefore, it is very suitable for sparse training data.

The Adagrad achieves this by storing all the past squared gradients.

Based on this method, the RMSprop proposes to restrict the window of accumulated past gradients by keeping an exponentially decaying average of past squared gradients, so as to reduce the aggressive learning rate reduction strategy.

Furthermore, besides the squared gradients, the Adam method also keeps an exponentially decaying average of gradients themselves.

The one last thing we need to notice in the training parameter is the last number 0.1. It denotes the training epochs, or how many times we should repeat on the whole dataset.

Here by taking a 0.1 epoch, we process only a tenth of all the training data for once.

After the training is finished, you can call Graph.model to generate a functional model to perform inference. Moreover, Graph module also provides functions such as save, load, print, to_string and so on to help you in manipulating the neural network.

Finally we can test the trained parameter on test set, by comparing the accuracy of correct inference result.

let test network =

let imgs, _, labels = Dataset.load_mnist_test_data () in

let m = Dense.Matrix.S.row_num imgs in

let imgs = Dense.Ndarray.S.reshape imgs [|m;28;28;1|] in

let mat2num x = Dense.Matrix.S.of_array (

x |> Dense.Matrix.Generic.max_rows

|> Array.map (fun (_,_,num) -> float_of_int num)

) 1 m

in

let pred = mat2num (Graph.model network imgs) in

let fact = mat2num labels in

let accu = Dense.Matrix.S.(elt_equal pred fact |> sum') in

Owl_log.info "Accuracy on test set: %f" (accu /. (float_of_int m))

The result shows that we can achieve an accuracy of 71.7% with only 0.1 epochs. Increase the training epoch to 1, and the accuracy will be improved to 88.2%. Further changing the epoch number to 2 can lead to an accuracy of about 90%. This result is OK, but not very ideal. Next we will see how a new type of neuron can improve the performance of the network dramatically.

Convolutional Neural Network

So far we have seen how an example of fully connected feed forward neural network evolves step by step. However, there is so much more than just this kind of neural networks. One of the most widely used is the convolution neural network (CNN).

We have seen the 1D convolution from signal processing chapter. The 2D convolution is similar, and the only difference is that now the input and filter/kernel are both matrices instead of vectors. As shown in the Signal chapter, the kernel matrix moves along the input matrix in both directions, and the sub-matrix on the input matrix is element-wisely multiplied with the kernel. This operation is especially good at capturing the features in images. It is the key to image process in neural networks.

To perform computer vision we need more types of neurons, and so far we have implemented most of the common type of neurons such as convolution (both 2D and 3D), pooling, batch normalisation, etc. They are enough to support building many state-of-the-art network structures. These neurons should be sufficient for creating from simple MLP to the most complicated convolution neural networks.

Since the MNIST handwritten recognition task is also a computer vision task, let’s use the CNN to do it again. The code below creates a small convolutional neural network of six layers.

let make_network input_shape =

input input_shape

|> lambda (fun x -> Maths.(x / F 256.))

|> conv2d [|5;5;1;32|] [|1;1|] ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> max_pool2d [|2;2|] [|2;2|]

|> dropout 0.1

|> fully_connected 1024 ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> linear 10 ~act_typ:Activation.(Softmax 1)

|> get_network

The training method is exactly the same as before, and the training accuracy we can achieve is about 93.3%, within only one 0.1 epoch. Compare this result to the previous simple feedforward network, and we can see the effectiveness of CNN.

Actually, the convolutional neural network is such an important driving force in the computer vision field that in the Part III of this book we have prepared three cases: image recognition, instance segmentation, and neural style transfer to demonstrate how we can use Owl to implement these state-of-art computer vision networks.

We will also introduce how these different neurons such as pooling work, how these networks are constructed etc.

Please check these chapters for more examples on building CNN in Owl.

Another great reference on this topic is the Stanford CS class CS231n: Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition. We refer you to its course notes for more detailed information.

Recurrent Neural Network

In all the previous examples, even the computer vision tasks, one pattern is obvious to see: given one input, the trained network generates another output. However, that’s not how every real world task works; in many cases the input data is in a sequence, and the output is updated based on the previous data in the sequence. For example, if we need to generate English based on French, or label each frame in a video, only focusing on the current word/frame is not enough.

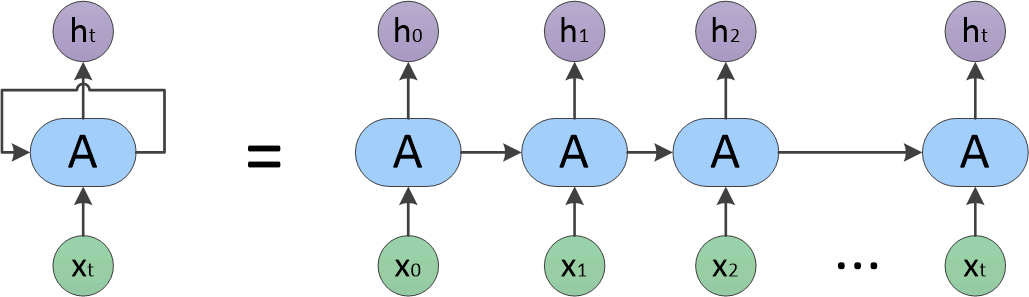

That’s where the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) comes to help. It allows the input and output to be in sequence. The basic structure of RNN is quite simple: it is a neural network with loops, and the output of the previous loop is fed into the next loop as input, together with the current data in sequence. In this way, the information from previous data in the sequence is kept.

As shown in this figure, a RNN can actually be unrolled into a chain of multiple connected neural networks. Here the \(x_i\)’s are sequential input, and the \(h_i\)’s are the hidden status, or output of the RNN. The function of RNN therefore mainly relies on the processing logic in \(A\).

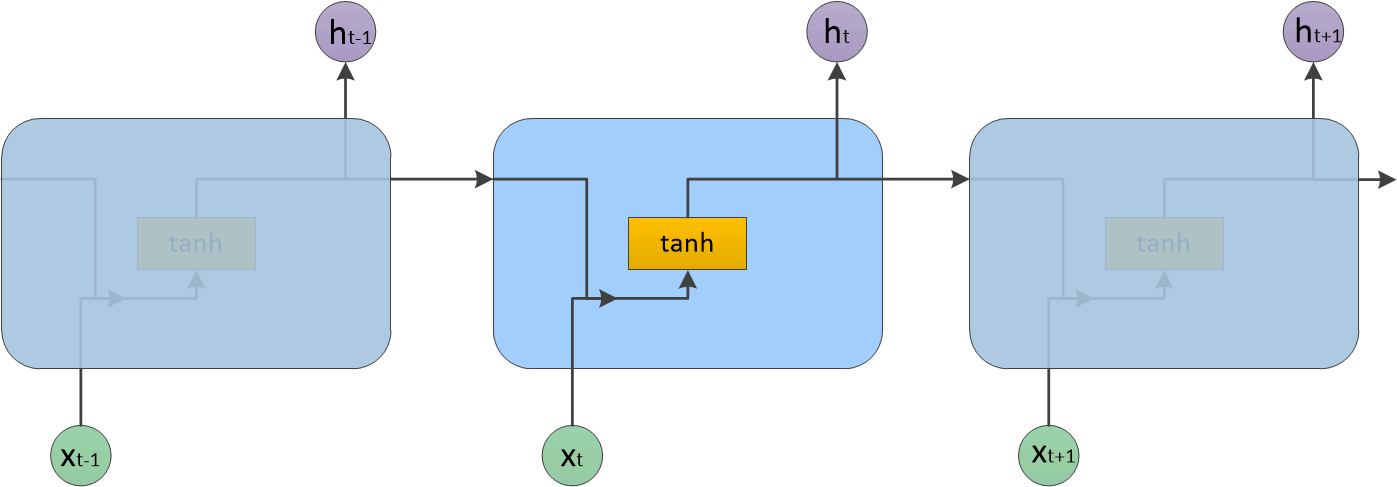

In a vanilla recurrent neural network, the function can be really simple and familiar:

\[h_i = \textrm{activation}(w(h_{i-1}x_i) + b).\]This is exactly what we have seen in the feed forward networks. Here w and b are the parameters to be trained in this RNN.

This process is shown in the figure above.

The activation function here is usually the tanh function to keep the value within range of [-1, 1].

However, this unit has a problem. Think about it: if you keep updating a diary based on input data; after a while, the information from the old days will certainly be flooded out by the new information. It’s like what Sherlock Holmes describes about how brain works: if you keep dumping information into your head, you will have to throw away existing stuff out, be it useful or not. As a result, in this RNN the old data in the sequence would have diminishing effect on the output, which means the output would be less sensitive to the context. That’s why currently when put into practical use, we often use a special kind of RNN: the Long/Short Term Memory (LSTM).

Long Short Term Memory (LSTM)

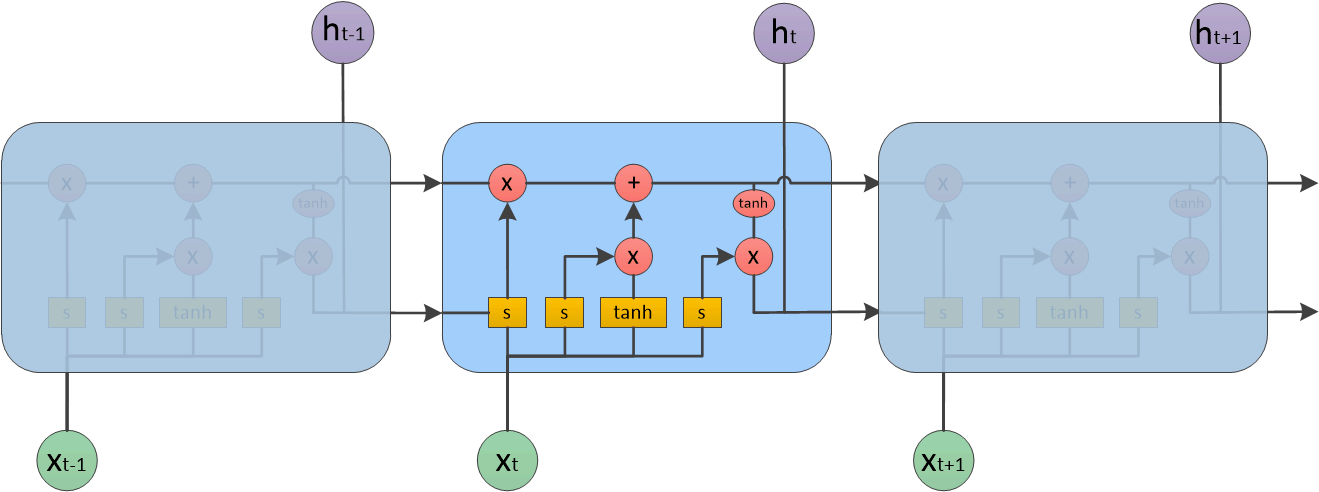

LSTM is proposed by Hochreiter & Schmidhuber (1997) and since widely used and refined by many work. Based on RNN, the basic idea of LSTM is simple. We still need to pass in the output from previous loop, but instead of take it as is, the processing unit makes three choices: 1) what to forget, 2) what to remember, and 3) what to output. In this way, the useful information from previous data can be kept longer and the RNN would then have a “longer memory”.

Let’s see how it achieves this effect. The process unit of LSTM is shown here. It consists of three parts that corresponds to the three choices listed above. Unlike standard RNN, each unit also takes in and produces a state \(C\) that flows along the whole loop process. This state is modified twice within the unit.

The first part is called forget gate layer.

It combines the output \(h_{t-1}\) from previous loop and the data \(x_i\), and outputs a probability number between [0, 1] to decide how much of the existing information should be kept.

This probability, as you may have guessed, is achieved using the sigmoid activation function, denoted by \(\sigma\).

Next, we need to decide “what to remember” from the existing data.

This is done with two branches.

The first branch uses the sigmoid function to denote which part of the new data \(h_{t-1}+x_t\) should be updated, and the second branch using the tanh function decides how much value to update for the vector.

Both branches follow the procedure, but with different w and b parameters.

By multiplying these two branches together, we know how much new information we should add to the information flow \(C\). The flow \(C\) is therefore first multiplied with the output from the forget gate to remove unnecessary information, and it adds the output from the second step to gain necessary know knowledge.

Now the only step left is to decide what to output.

This time it first runs a sigmoid function again to decide which part of information flow \(C\) to keep, and then applies this filter to a tanh-scaled information flow to finally get the output \(h_t\).

LSTM is widely used in time-series related applications such as speech recognition, time-series prediction, human action recognition, robot control, etc. Using the neural network module in Owl, we can easily built a RNN that generates text by itself, following the style of the input text.

open Neural.S

open Neural.S.Graph

let make_network wndsz vocabsz =

input [|wndsz|]

|> embedding vocabsz 40

|> lstm 128

|> linear 512 ~act_typ:Activation.Relu

|> linear vocabsz ~act_typ:Activation.(Softmax 1)

|> get_network

That’s it. The network is even simpler than that of the CNN. The only parameter we need to specify in building the LSTM is the length of vectors. However, the generated computation graph is way more complicated due to LSTM’s internal recurrent structure. You can download the high-resolution file to take a look if you are interested.

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

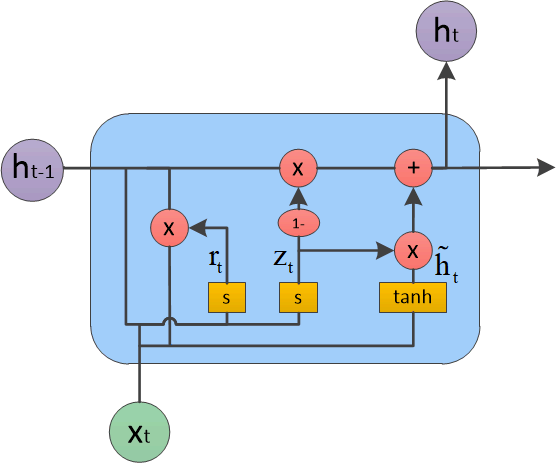

The LSTM has been refined in later work since its proposal. There are many variants of it, and one of them is the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) which is proposed by Cho, et al. in 2014. Its processing unit is shown in the figure below.

Compared to LSTM, the GRU consists of two parts.

The first is a “reset gate” that decides how much information to forget from the past, and the “update gate” behaves like a combination of LSTM’s forget and input gate.

Besides, it also merges the information flow \(C\) and output status \(h\).

With these changes, the GRU can achieve the same effect as LSTM with fewer operations, and therefore is a bit faster than LSTM in training.

In the LSTM code above, we can just replace the lstm node to gru.

Generative Adversarial Network

There is one more type of neural network we need to discuss. Actually it’s not a particular type of neural network with new neurons like DNN or RNN, but more like a huge family of networks that shows a particular pattern. A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) consists of two parts: generator and discriminator. During training, the generator tries its best to synthesises images based on existing parameters, and the discriminator tries its best to separate the generated data and true data. This mutual deception process is iterated until the discriminator can no longer tell the difference between the generated data and the true data (which means us human beings are also not very like to do that).

It might still be difficult to fathom how does a GAN work in action only by text introduction. Let’s look at an example. Previously we have used the MNIST dataset extensively in image recognition task, but now let’s try something different with it. Say we want to build a neural network that can produce a digit picture that looks like it’s taken from the MNIST dataset. It doesn’t matter which digits; the point is being “real”, since this output is actually NOT in the dataset.

To generate such an image does not really need too complicated network structure. For example, we can use something like below (Reference):

open Neural.S

open Neural.S.Graph

open Neural.S.Algodiff

let make_generator input_shape =

let out_size = Owl_utils_array.fold_left ( * ) 1 input_shape in

input input_shape

|> fully_connected 256 ~act_typ:(Activation.LeakyRelu 0.2)

|> normalisation ~decay:0.8

|> linear 512 ~act_typ:(Activation.LeakyRelu 0.2)

|> normalisation ~decay:0.8

|> linear 1024 ~act_typ:(Activation.LeakyRelu 0.2)

|> normalisation ~decay:0.8

|> linear out_size ~act_typ:Activation.Tanh

|> reshape input_shape

|> get_network

We pile up multiple linear layers, activation layers, and normalisation layers.

We don’t even have to use the convolution layer.

By now you should be familiar with this kind of network structure.

This network accepts an ndarray of image shape 28x28 and outputs an ndarray of the same shape, i.e. a black and white image.

Besides this generator, the other half of the GAN is the discriminator. The structure is also quite simple:

let make_discriminator input_shape =

input input_shape

|> fully_connected 512 ~act_typ:(Activation.LeakyRelu 0.2)

|> linear 256 ~act_typ:(Activation.LeakyRelu 0.2)

|> linear 1 ~act_typ:Activation.Sigmoid

|> get_network

The discriminator takes in the image as input.

The output from this network is only one value. Since we apply the sigmoid activation function on it, this output means the probability how good the discriminator thinks the outputs from generator are.

An output of 1 means the discriminator think this output is taken from MNIST and 0 means the input is obviously a fake.

The question is: how to train these two parts so that they can do their own job perfectly?

Here is how the loss values are constructed.

Let’s assume that we each time we only take one picture from MNIST and training data.

First, to train the discriminator, we consider the ground truth: we know that the data taken from MNSIT must be true, so it is labelled 1; on the other hand, we know that anything that comes from generator, however good it is, must be a fake, and thus labelled 0.

By adding these two parts together, we can get loss value for training the discriminator.

The point of this step is to make the discriminator to tell the output from generators from the true images as effectively as possible.

With the same batch of training data, we also want to train the generator.

The strategy is totally the reverse now.

We combine the generator network and discriminator network together, give it a random noise image as input, and label the true output as 1, even though we know that at the begin the output from generator would be totally fake.

The loss value is got from comparing the output of this combined network and the true label 1.

During the training of this loss value, we need to make the discriminator as non-trainable.

The point of this step is to make generator produce images that can fool the discriminator as convincingly as possible.

That’s all. It’s kind of like a small scale Darwinism simulation. By iteratively strengthening both parties, the generator can finally become so good that even a good discriminator cannot tell if an input image is faked by the generator or really taken from MNIST. At that stage, the generator is trained well and the job is done.

This approach is successfully applied in many applications, such as Pix2Pix, face ageing, increase photo resolution, etc. For Pix2Pix, you give it a pencil-drawn picture of bag and it can render it into a real-looking bag. Or think about the popular applications that create an animation character that does not really exist previously. In these applications, the generators are all required to generate images that just do not exist but somehow are real enough to fool the people to think that they do exist in the real world. They may require much more complex network structure, but the general idea of GAN would be the same as what we have introduced.

Summary

This chapter is not yet another “hello world” level tutorial about using the neural network API of a framework. Instead, in this chapter we give a detail introduction to the theory behind neural networks and how a neural network module is constructed in Owl.

We start with the most basic and early form of neural network: perceptron, and then manually build a feedforward network to perform multi-class handwritten digit recognition task by extending the logistic regression. Next, we introduce the Neural Network module, including how its core part works and how it is built step by step. Here we use the Owl API to solve the same example, including training and testing. The training parameter setting regression module in Owl is explained in detail. We then introduce two important types of neural network: the convolutional neural network, together its superior performance against simple feedforward network, and the recurrent neural network, including two of its variants: the LSTM and GRU. We finish this chapter with a brief introduction of the basic idea behind Generative Adversarial Network, another type of neural network that has gained a lot of momentum in research and application recently.