Slicing and Broadcasting

Indexing, slicing, and broadcasting are three fundamental functions to manipulate multidimensional arrays. They are used in practically every numerical application. Therefore understanding their nuts and bolts is very important. In this chapter we will introduce how to use these functions in Owl.

Slicing

Indexing and slicing is arguably the most important function in any numerical library. A flexible design is able to significantly simplify the code and allow us to write concise algorithms. Before we start, let’s clarify some things:

-

slicing refers to the operation that extracts part of the data from an ndarray or a matrix according to a well-defined slice definition;

-

slicing can be applied to all dense data structures, i.e. both ndarrays and matrices;

-

slice definition is an

index listwhich clarifies what indices should be accessed and in what order for each dimension of the passed in variable; -

there are two types of slicing in Owl: basic slicing and fancy slicing. The difference between the two lies in how the slice is defined.

Basic Slicing

For basic slicing, each dimension in the slice definition must be defined in the format of [start:stop:step]. Owl provides two functions get_slice and set_slice to retrieve and assign slice values respectively.

val get_slice : int list list -> ('a, 'b) t -> ('a, 'b) t

val set_slice : int list list -> ('a, 'b) t -> ('a, 'b) t -> unit

Both functions accept int list list as its slice definition. Every list element in the int list list is assumed to be a range.

For example, [ []; [2]; [-1;3] ] is equivalent to its full slice definition [ R []; R [2]; R [-1;3] ], as we will introduce below in the fancy slicing.

Fancy Slicing

Fancy slicing is more powerful than the basic one thanks to its slice definition. With fancy slicing, we can pass in a list of arbitrarily ordered indices which may not be possible to specify with aforementioned simple [start;stop;step] format.

type index =

| I of int (* single index *)

| L of int list (* list of indices *)

| R of int list (* index range *)

As shown above, fancy slice is defined by an index list where you can use three type constructors to specify:

- an individual index (using

Iconstructor); - a list of indices (using

Lconstructor); - a range of indices (using

Rconstructor).

Similar to the basic slicing, there are two functions to handle fancy slicing operations.

val get_fancy : index list -> ('a, 'b) t -> ('a, 'b) t

val set_fancy : index list -> ('a, 'b) t -> ('a, 'b) t -> unit

The get_fancy s x retrieves a slice of x defined by s; whereas set_fancy s x y assigns the slice of x defined by s according to values in y. Note that y must have the same shape as that defined by s.

Basic slicing is a special case of fancy slicing where only type constructor R is used in the definition. For example, the following two definitions are equivalent.

let x = Arr.sequential [|10; 10; 10|];;

Arr.get_slice [ []; [0;8]; [3;9;2] ] x;;

Arr.get_fancy [ R[]; R[0;8]; R[3;9;2] ] x;;

Note that both get_basic and get_fancy return a copy rather than a view as that in NumPy; whilst set_basic and set_fancy modifies the original data in place.

Conventions in Definition

Essentially, Owl’s slicing functions are very similar to those in NumPy. So if you already know how to slice n-dimensional arrays in NumPy, you should find this chapter quite easy to follow.

The core building block is the slice definition. Slice definition is an index list. Each element within the index list corresponds to one dimension in the passed in data, and it defines how the indices along this dimension should be accessed. Owl provides three constructors I, L, and R to let you specify single index, a list of indices, or a range of indices.

Constructor I is trivial, it specifies an index. E.g., [ I 2; I 5 ] returns the element at position (2, 5) in a matrix.

Constructor L is used to specify a list of indices. E.g., [ I 2; L [5;3] ] returns a 1 x 2 matrix consists of the elements at (2, 5) and (2, 3) in the original matrix.

Constructor R is for specifying a range of indices. It has more conventions but by no means complicated. The following text is dedicated for range conventions.

These conventions or rules require our attentions in order to write correct slice definition. These conventions can be equally applied to both basic and fancy slicing.

Rule #1: The format of the range definition follows R [ start; stop; step ]. Obviously, start specifies the starting index; stop specifies the stopping index (inclusive); and step specifies the step size. You do not have to specify all three variables in the definition; please see the following rules.

Rule #2: All three variables start, stop, and step can take both positive and negative values, but step is not allowed to take 0 value. Positive step indicates that indices will be visited in increasing order from start to stop; and vice versa.

Rule #3: For start and stop variables, positive value refers to a specific index; whereas negative value a will be translated into n + a where n is the total number of indices. E.g., [ -1; 0 ] means from the last index to the first one.

Rule #4: If you pass in an empty list R [], this will be expanded into [ 0; n - 1; 1 ] which means all the indices will be visited in increasing order with step size 1.

Rule #5: If you only specify one variable such as [ start ], get_slice function assumes that you will take one specific index by automatically extending it into [ start; start; 1 ]. As we can see, start and stop are the same, with step size 1.

Rule #6: If you only specify two variables then slice function assumes they are [ start; stop ] which defines the range of indices. However, how get_slice will expand this slice definition depends. As we can see below, slice will visit the indices in different orders:

- if

start <= stop, it will be expanded to[ start; stop; 1 ]; - if

start > stop, it will be expanded to[ start; stop; -1 ];

Rule #7: It is not necessary to specify all the definitions for all the dimensions, get_slice function will also expand it by assuming you will take all the data in higher dimensions. E.g., x has the shape [ 2; 3; 4 ], if we define the slice as [ [0] ] then get_slice will expand the definition into [ [0]; []; [] ]

OK, that’s all. Please make sure you understand it well before you start, but it is also fine you just learn by doing.

Now here are some illustrated examples that can get you started with some of these rules.

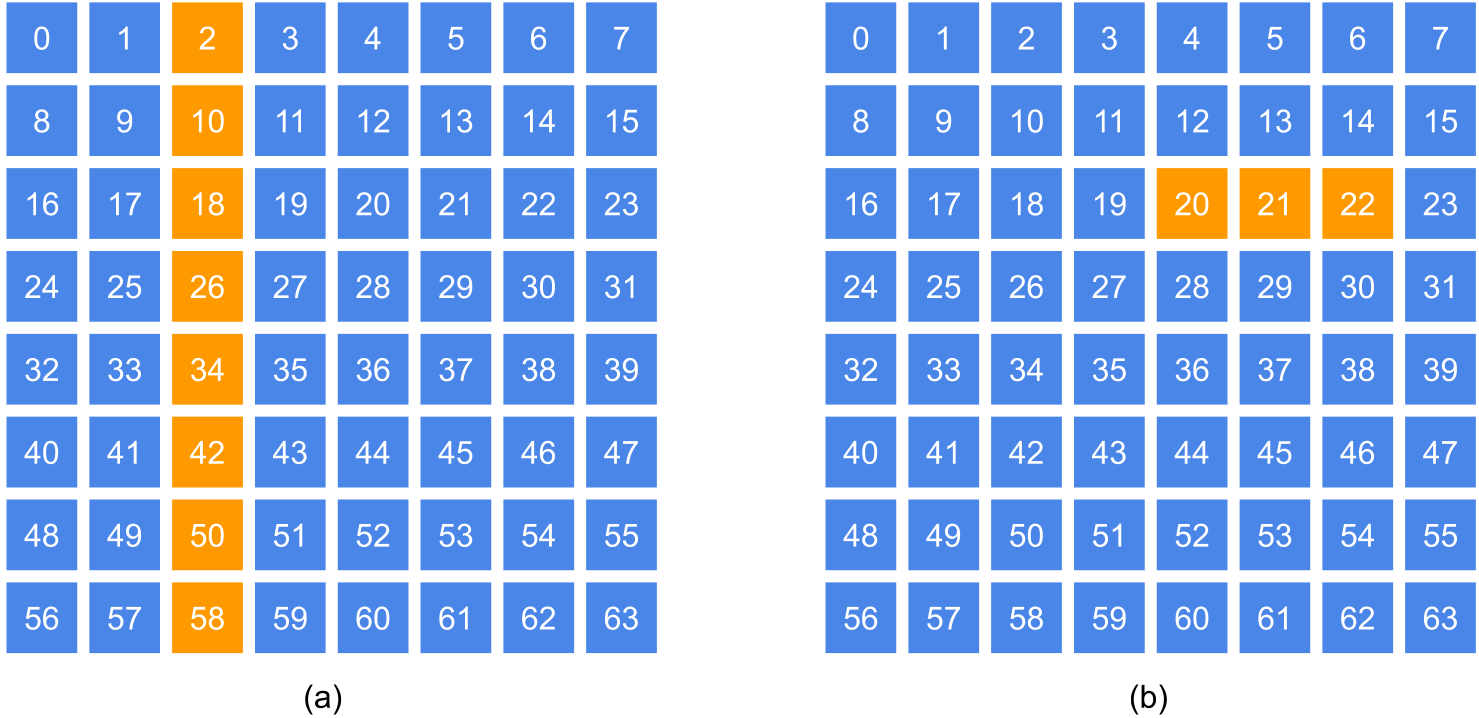

These examples are based on a 8x8 matrix.

let x = Arr.sequential [|8; 8|]

The first example is to take one column of this matrix. It can be achieved by using both basic and fancy slicing:

# Arr.get_fancy [ R[]; I 2 ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0

R0 2

R1 10

R2 18

R3 26

R4 34

R5 42

R6 50

R7 58

# Arr.get_slice [ []; [2] ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0

R0 2

R1 10

R2 18

R3 26

R4 34

R5 42

R6 50

R7 58

The second example is similar, but about retrieving part of a row. Still, this can be gotten using both methods.

# Arr.get_fancy [ I 2; R [4; 6] ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 20 21 22

# Arr.get_slice [ [2]; [4; 6] ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 20 21 22

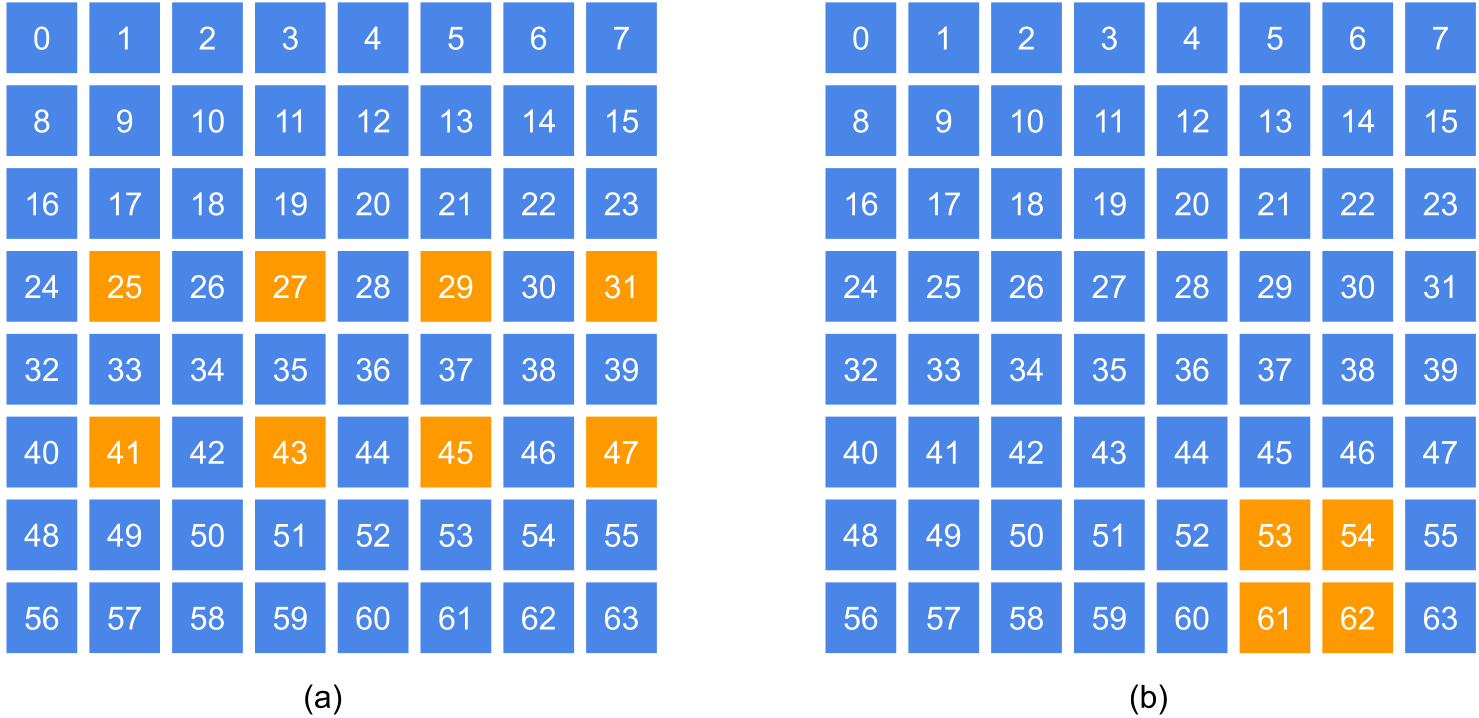

The next example is a bit more complex. It chooses certain rows, and then choose the columns by a fixed step 2. We can use the fancy slicing in this way:

# Arr.get_fancy [ L [3; 5]; R [1; 7; 2] ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2 C3

R0 25 27 29 31

R1 41 43 45 47

Finally, the last example concerns taking a sub matrix. We can do it in the similar way as the example 1 and 2. Or, since this sub matrix is close to the end of both dimension, we can use the negative integers as indices.

# Arr.get_fancy [ L [-2; -1]; R [-3; -2] ] x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1

R0 53 54

R1 61 62

Extended Operators

The operators for indexing and slicing are built on the extended indexing operators introduced in OCaml 4.06. All of them are defined in the functors in Owl_operator module. They are used in Owl as follows.

.%{ }:get.%{ }<-:set.${ }:get_slice.${ }<-:set_slice.!{ }:get_fancy.!{ }<-:set_fancy

Here are some examples that show how to use them.

.%{ } for indexing:

open Arr;;

let x = sequential [|10; 10; 10|];;

let a = x.%{2; 3; 4};; (* i.e. Arr.get *)

x.%{2; 3; 4} <- 111.;; (* i.e. Arr.set *)

.${ } for basic slicing:

open Arr;;

let x = sequential [|10; 10; 10|] in

let a = x.${[0;4]; [6;-1]; [-1;0]} in (* i.e. Arr.get_slice *)

let b = zeros (shape a) in

x.${[0;4]; [6;-1]; [-1;0]} <- b;; (* i.e. Arr.set_slice *)

.!{ } for fancy slicing:

open Arr;;

let x = sequential [|10; 10; 10|] in

let a = x.!{L [2;2;1]; R [6;-1]; I 5} in (* i.e. Arr.get_fancy *)

let b = zeros (shape a) in

x.!{L [2;2;1]; R [6;-1]; I 5} <- b;; (* i.e. Arr.set_fancy *)

Advanced Usage

There are more advanced usages of slicing besides what we have just seen. We will first use the basic slicing to demonstrate some examples in this section. Note that all the following examples can be equally applied to ndarray.

Let’s first define a sequential matrix as the input data for the following examples.

# let x = Mat.sequential 5 7;;

val x : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6

R0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

R1 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

R2 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

R3 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

R4 28 29 30 31 32 33 34

Now, we can start our experiment. One benefit of running code in utop is that you can observe the output immediately to understand better how slice function works.

let x = Arr.sequential [|10; 10; 10|];;

(* simply take all the elements *)

let s = [ ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take row 2 *)

let s = [ [2]; [] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* same as above, take row 2, but only specify low dimension slice definition *)

let s = [ [2] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take from row 1 to 3 *)

let s = [ [1;3] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take from row 3 to 1, same as the example above but in reverse order *)

let s = [ [3;1] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

Let’ see some more complicated examples.

(* take from row 1 to 3 and column 3 to 5, so a sub-matrix of x *)

let s = [ [1;3]; [3;5] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take from row 1 to the last row *)

let s = [ [1;-1]; [] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take the rows of even number indices, i.e., 0;2;4 *)

let s = [ [0;-1;2] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take the column of odd number indices, i.e.,1;3;5 ... *)

let s = [ []; [1;-1;2] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* reverse all the rows of x *)

let s = [ [-1;0] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* reverse all the elements of x, same as applying reverse function *)

let s = [ [-1;0]; [-1;0] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

(* take the second last row, from the first column to the last, with step size 3 *)

let s = [ [-2]; [0;-1;3] ] in

Mat.get_slice s x;;

The following are some more advanced examples to show how to use slicing to achieve quite complicated operations. Let’s use a 5 x 5 sequential matrix for illustration.

# let x = Mat.sequential 5 5;;

val x : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4

R0 0 1 2 3 4

R1 5 6 7 8 9

R2 10 11 12 13 14

R3 15 16 17 18 19

R4 20 21 22 23 24

The first function flip a matrix upside down, i.e. flip vertically.

# let flip x = Mat.get_slice [ [-1; 0]; [ ] ] x in

flip x;;

- : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4

R0 20 21 22 23 24

R1 15 16 17 18 19

R2 10 11 12 13 14

R3 5 6 7 8 9

R4 0 1 2 3 4

The second reverse function treats a matrix as one-dimensional vector and reverse its elements. This operation is equivalent to flipping in both vertical and horizontal directions.

# let reverse x = Mat.get_slice [ [-1; 0]; [-1; 0] ] x in

reverse x;;

- : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4

R0 24 23 22 21 20

R1 19 18 17 16 15

R2 14 13 12 11 10

R3 9 8 7 6 5

R4 4 3 2 1 0

The third function rotates a matrix 90 degrees in clockwise direction. As we can see, slicing function leads to very concise code.

# let rotate90 x = Mat.(transpose x |> get_slice [ []; [-1;0] ]) in

rotate90 x;;

- : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4

R0 20 15 10 5 0

R1 21 16 11 6 1

R2 22 17 12 7 2

R3 23 18 13 8 3

R4 24 19 14 9 4

The last function cshift performs right circular shift along the columns of a matrix.

let cshift x n =

let c = Mat.col_num x in

let h = Utils.Array.(range (c - n) (c - 1)) |> Array.to_list in

let t = Utils.Array.(range 0 (c - n -1)) |> Array.to_list in

Mat.get_fancy [ R []; L (h @ t) ] x

Applying to the previous x, the outcome should look like this.

# cshift x 2;;

- : Mat.mat =

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4

R0 3 4 0 1 2

R1 8 9 5 6 7

R2 13 14 10 11 12

R3 18 19 15 16 17

R4 23 24 20 21 22

Slicing and indexing is an important topic in Owl, so make sure you understand it well before proceeding to other chapters.

Broadcasting

Following indexing and slicing introduced in the previous section, this section introduces the broadcasting operation in Owl. In contrast to indexing and slicing which are explicitly used, broadcasting are often implicitly called when certain conditions are met. This automatic behaviour on one hand is able to simplify the code, on the other it can also potentially introduce bugs and make the debugging really difficult.

What Is Broadcasting?

There are many binary (mathematical) operators that take two ndarrays as inputs, e.g. add, sub, etc. In a trivial case, the inputs have exactly the same shape. However, in many real-world applications, we need to operate on two ndarrays whose shapes do not match.

How to apply the smaller one to the bigger one is referred to as broadcasting.

Broadcasting can save unnecessary memory allocation. For example, assume we have a 1000 x 500 matrix x containing 1000 samples, and each sample has 500 features. Now we want to add a bias value for each feature, i.e. a bias vector v of shape 1 x 500.

Because the shape of x and v do not match, we need to tile v so that it has the same shape as that of x.

let x = Mat.uniform 1000 500;; (* generate random samples *)

let v = Mat.uniform 1 500;; (* generate random bias *)

let u = Mat.tile v [|1000;1|];; (* align the shape by tiling *)

Mat.(x + u);;

The code above certainly works, but it is obvious that the solution uses too much memory. High memory consumption is not desirable for many applications, especially for those running on resource-constrained devices. Therefore we need the broadcasting.

let x = Mat.uniform 1000 500;; (* generate random samples *)

let v = Mat.uniform 1 500;; (* generate random bias *)

Mat.(x + u);; (* returns 1000 x 500 ndarray *)

Shape Constraints

In broadcasting, the shapes of two inputs cannot be arbitrarily different, they must be subject to some constraints. The convention used in broadcasting operation is much simpler than slicing. Given two matrices/ndarrays of the same dimensionality, for each dimension, one of the following two conditions must be met: 1) both are equal; 2) either is one.

Here are some valid shapes where broadcasting can be applied between x and y.

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 1; 1; 1 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 2; 1; 1 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 2; 3; 1 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 2; 3; 3 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 1; 1; 3 |]

...

Here are some invalid shapes that violate the aforementioned constraints so that the broadcasting cannot be applied.

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 1; 1; 2 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 3; 1; 1 |]

x : [| 2; 1; 3 |] y : [| 3; 1; 1 |]

...

What if y has less dimensionality than x? E.g., x has the shape [|2;3;4;5|] whereas y has the shape [|4;5|]. In this case, Owl first calls Ndarray.expand function to increase y’s dimensionality to the same number as x’s. Technically, two ndarrays are aligned along the highest dimension. In other words, this is done by appending 1 s to lower dimension of y, so the new shape of y becomes [|1;1;4;5|].

You can try expand by yourself, as shown below.

let y = Arr.sequential [|4;5|];;

let y' = Arr.expand y 4;;

# Arr.shape y';;

- : int array = [|1; 1; 4; 5|]

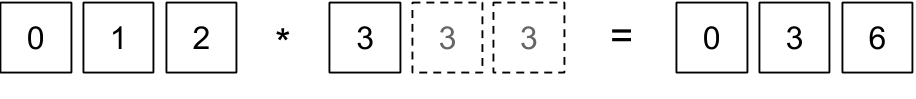

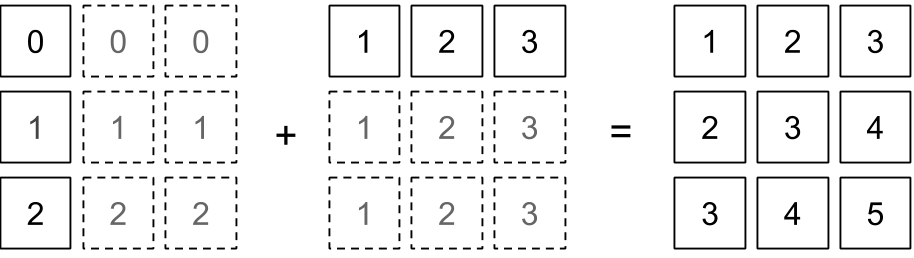

If these seem too abstract, here are three concrete 2D examples for you to better understand how the shapes are extended in the broadcasting. The first example is vector multiplied by scalar.

let a = Arr.sequential [|1;3|]

# Arr.add_scalar a 3.;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 3 4 5

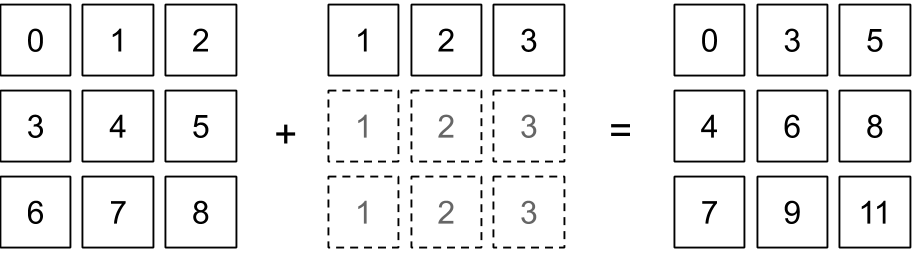

The second example is matrix plus vector.

let b0 = Arr.sequential [|3;3|]

let b1 = Arr.sequential ~a:1. [|1;3|]

# Arr.mul b0 b1;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 2 6

R1 3 8 15

R2 6 14 24

The third example is column vector plus row vector.

let c0 = Arr.sequential [|3;1|]

let c1 = Arr.copy b1

# Arr.mul c0 c1;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 0 0

R1 1 2 3

R2 2 4 6

Supported Operations

The broadcasting operation is transparent to programmers, which means it will be automatically applied if the shapes of two operators do not match (given the constraints are met of course). Currently, the operations in Owl that support broadcasting are listed below:

- basic computation:

add,sub,mul,div,pow - comparison operations:

elt_equal,elt_not_equal,elt_less,elt_greater,elt_less_equal,elt_greater_equal - other operations:

min2,max2.atan2,hypot,fmod

Slicing in NumPy and Julia

The indexing and slicing functions are fundamental in all the multi-dimensional array implementations in various other libraries. For example, the previous examples can be implemented using NumPy with code below.

>> import numpy as np

>> x = np.arange(64).reshape([8,8])

>> x[:, 2]

array([ 2, 10, 18, 26, 34, 42, 50, 58])

>> x[2, 4:7]

array([20, 21, 22])

>> x[[3,5], 1:8:2]

array([[25, 27, 29, 31],

[41, 43, 45, 47]])

>> x[[-2,-1], -3:-1]

array([[53, 54],

[61, 62]])

You can see that the basic indexing syntax are similar, only that Python is not strong-typed, so the users can mix single index, list of indices, or index range at will. Note that index range in NumPy is different from that in Owl.

Also, in Julia it can be done with:

> x = transpose(reshape([0:1:63;],8 ,8))

> x[:, 3]

8-element Array{Int64,1}:

2

10

18

26

34

42

50

58

> x[3, 5:7]

3-element Array{Int64,1}:

20

21

22

> x[[4,6], 2:2:8]

2x4 Array{Int64,2}:

25 27 29 31

41 43 45 47

> x[7:8, [6,7]]

2x2 Array{Int64,2}:

53 54

61 62

The Julia interface is also similar to that of NumPy. However, there are some crucial differences as shown in these examples.

First, the array in Julia uses column-major order, so we need to use the transpose function to build the same example.

The other obvious difference is that, the indexing of Julia array starts from 1, not 0.

Besides, the negative indexing is not supported in Julia.

One important thing to notice in slicing is the difference between copy and view. For example, in Owl we can make a slice, change the slice, and check what the original ndarray looks like.

# let x = Arr.sequential [|3;3|];;

val x : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 1 2

R1 3 4 5

R2 6 7 8

# let y = Arr.get_slice [[0]; []] x;;

val y : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 1 2

# Arr.set y [|0; 2|] 200.;;

- : unit = ()

# y;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 1 200

# x;;

- : Arr.arr =

C0 C1 C2

R0 0 1 2

R1 3 4 5

R2 6 7 8

We can see that in Owl, changing the local content of the slice y does not change that of the original ndarray x.

That’s because in Owl each slice makes a different copy.

As a contrast, in NumPy the default indexing only makes a “view” of the original array, and any change on the view will also change the original array.

>> x = np.arange(9).reshape([3,3])

array([[0, 1, 2],

[3, 4, 5],

[6, 7, 8]])

>> y = x[0, :]

array([0, 1, 2])

>> y[2] = 200

>> y

array([ 0, 1, 200])

>> x

array([[ 0, 1, 200],

[ 3, 4, 5],

[ 6, 7, 8]])

Internal Mechanism

To achieve good performance, slicing is implemented with C in Owl.

The basic algorithm of slicing is simple. We need to copy part of the source array x to the target array y.

So you can imagine two cursors move one step at a time, only that for each dimension, the cursor start at different position and offset compared to the starting point, and at different increments.

At each step, we simply copy the content from x to y.

To do this, we define a structure slice_pair for slicing operations.

struct slice_pair {

int64_t dim; // number of dimensions, x and y must be the same

int64_t dep; // the depth of current recursion.

intnat *n; // number of iteration in each dimension, i.e. y's shape

void *x; // x, source if operation is get, destination if set.

int64_t posx; // current offset of x.

int64_t *ofsx; // offset of x in each dimension.

int64_t *incx; // stride size of x in each dimension.

void *y; // y, destination if operation is get, source if set.

int64_t posy; // current offset of y.

int64_t *ofsy; // offset of y in each dimension.

int64_t *incy; // stride size of y in each dimension.

};

Taking a 2-dimensional slicing as example, here is the core step:

for (int64_t i0 = 0; i0 < n0; i0++) {

posx1 = posx0 + ofsx1;

posy1 = posy0 + ofsy1;

for (int64_t i1 = 0; i1 < n1; i1++) {

MAPFUN (*(x + posx1), *(y + posy1));

posx1 += incx1;

posy1 += incy1;

}

posx0 += incx0;

posy0 += incy0;

}

So this algorithm basically says that for each row, we calculate its starting points in x and y; for each column, copy the element; and then move the cursors forward until the current row is finished.

And then move the rows forward.

If it becomes multiple dimension, we implement it with recursive algorithm.

Summary

In this chapter we introduce the fundamental operation for ndarrays in a numerical library: the slicing, indexing, and broadcasting. These topics are not difficult, but mastering them takes practice. This chapter provides a lot examples and illustrations. Hope they can be of help to the readers. We also briefly list how the slicing is done in NumPy and Julia, so that the users can see the similarities and differences between Owl and them. In the last of this chapter, we briefly introduce the implementation mechanism of slicing in Owl, for those who are interested in the low level details. More will be discussed in the Part II of this book.