- Statistical Functions

Statistical Functions

Statistics is an indispensable tool for data analysis, it helps us to gain the insights from data. The statistical functions in Owl can be categorised into three groups: descriptive statistics, distributions, and hypothesis tests.

Random Variables

We start from assigning probabilities to events. A event may comprise of finite or infinite number of possible outcomes. All possible output make up the sample space. To better capture this assigning processes, we need the idea of Random Variables.

A random variable is a function that associate sample output of events with some numbers of interests.

Imagine the classic tossing coin game, we toss the coin four times, and the result is “head”, “head”, “tail”, “head”.

We are interested in the number of “head” in this outcome. So we make a Random Variable “X” to denote this number, and X(["head", "head", "tail", "head"]) = 3.

You can see that using random variables can greatly reduce the event sample space.

Depending on the number of values it can be, a random variable can be broadly categorised into Discrete Random Variable (with finite number of possible output), and Continuous Random Variable (with infinite number of possible output).

Discrete Random Variables

Back to the coin tossing example. Suppose that the coin is specially minted so that the probability of tossing head is \(p\). In this scenario, we toss for three times. Use the number of heads as a random variable \(X\), and it contains four possible outcomes: 0, 1, 2, or 3.

We can calculate the possibility of each output result. Since each toss is a individual trial, the possibility of three heads P(X=2) is \(p^3\).

Two heads includes three cases: HHT, HTH, THH, each has a probability of \(p^2(1-p)\), and together \(P(X=2) = 3p^2(1-p)\).

Similarly \(P(X=1)=3p(1-p)^2\), and \(P(X=0)=(1-p)^3\).

Formally, consider a series of \(n\) independent trails, each trail containing two possible results, and the result of interest happens at a possibility of \(p\), then the possibility distribution of random variable \(X\) is (\(X\) being the number of result of interests):

\(P(X=k) = {N\choose k} p^k(1-p)^{n-k}.\) {#eq:stats:binomial_pdf}

This type of distribution is called the Binomial Probability Distribution.

We can stimulate this process of tossing coins with the Stats.binomial_rvs function.

Suppose the probability of tossing head is 0.4, and for 10 times.

# let _ =

let toss = Array.make 10 0 in

Array.map (fun _ -> Stats.binomial_rvs 0.3 1) toss

- : int array = [|0; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0; 1; 0|]

The equation is called the &probability density function (PDF) of this binomial distribution. Formally the PDF of random variable X is denoted with \(p_X(k)\) and is defined as:

\[p_X(k)=P({s \in S | X(s) = k}),\]where \(S\) is the sample space. This can also be expressed with the code:

# let x = [|0; 1; 2; 3|]

val x : int array = [|0; 1; 2; 3|]

# let p = Array.map (Stats.binomial_pdf ~p:0.3 ~n:3) x

val p : float array =

[|0.342999999999999916; 0.440999999999999837; 0.188999999999999918;

0.0269999999999999823|]

# Array.fold_left (+.) 0. p

- : float = 0.999999999999999778

Aside from the PDF, another related and frequently used idea is to see the probability of random variable \(X\) being within a certain range: \(P(a \leq X \leq b)\). It can be rewritten as \(P(X \leq b) - P(X \leq a - 1)\). Here the term \(P(X \leq t)\) is called the Cumulative Distribution Function of random variable \(X\). For the binomial distribution, it CDF is:

\[p(X\leq~k)=\sum_{i=0}^k{N\choose i} p^k(1-p)^{n-i}.\]We can calculate the CDF in the 3-tossing problem with code again.

# let x = [|0; 1; 2; 3|]

val x : int array = [|0; 1; 2; 3|]

# let p = Array.map (Stats.binomial_cdf ~p:0.3 ~n:3) x

val p : float array = [|0.342999999999999972; 0.784; 0.973; 1.|]

Continuous Random Variables

Unlike discrete random variable, a continuous random variable has infinite number of possible outcomes. For example, in uniform distribution, we can pick a random real number between 0 and 1. Apparently there can be infinite number of outputs.

One of the most widely used continuous distribution is no doubt the Gaussian distribution. It’s probability function is a continuous one: \(p(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi~\delta}}e^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{t - \mu}{\sigma}\right)^2}\)

Here the \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are parameters. Depending on them, the \(p(x)\) can take different shapes. Let’s look at an example.

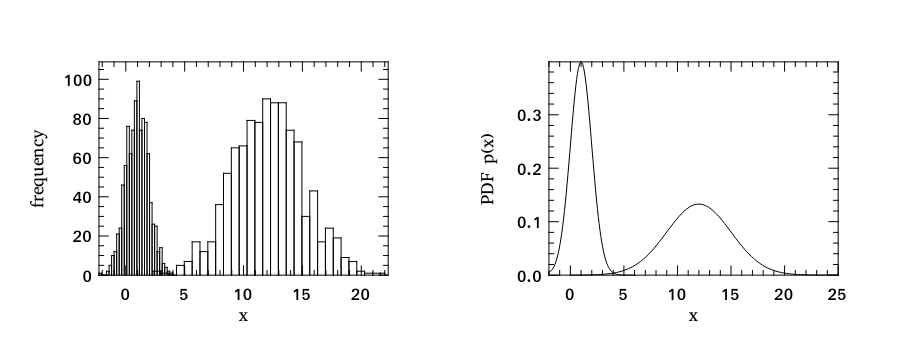

We generate two data sets in this example, and both contain 999 points drawn from different Gaussian distribution \(\mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^{2})\). For the first one, the configuration is \((\mu = 1, \sigma = 1)\); whilst for the second one, the configuration is \((\mu = 12, \sigma = 3)\).

let noise sigma = Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:0. ~sigma;;

let x = Array.init 999 (fun _ -> Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:1. ~sigma:1.);;

let y = Array.init 999 (fun _ -> Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:12. ~sigma:3.);;

We can visualise the data sets using histogram plot as below. When calling histogram, we also specify 30 bins explicitly. You can also fine tune the figure using spec named parameter to specify the colour, x range, y range, etc. We will discuss in details on how to use Owl to plot in a separate chapter.

(* convert arrays to matrices *)

let x' = Mat.of_array x 1 999;;

let y' = Mat.of_array y 1 999;;

(* plot the figures *)

let h = Plot.create ~m:1 ~n:2 "plot_02.png" in

Plot.subplot h 0 0;

Plot.set_ylabel h "frequency";

Plot.histogram ~bin:30 ~h x';

Plot.histogram ~bin:30 ~h y';

Plot.subplot h 0 1;

Plot.set_ylabel h "PDF p(x)";

Plot.plot_fun ~h (fun x -> Stats.gaussian_pdf ~mu:1. ~sigma:1. x) (-2.) 6.;

Plot.plot_fun ~h (fun x -> Stats.gaussian_pdf ~mu:12. ~sigma:3. x) 0. 25.;

Plot.output h;;

In subplot 1, we can see the second data set has much wider spread. In subplot 2, we also plot corresponding the probability density functions of the two data sets.

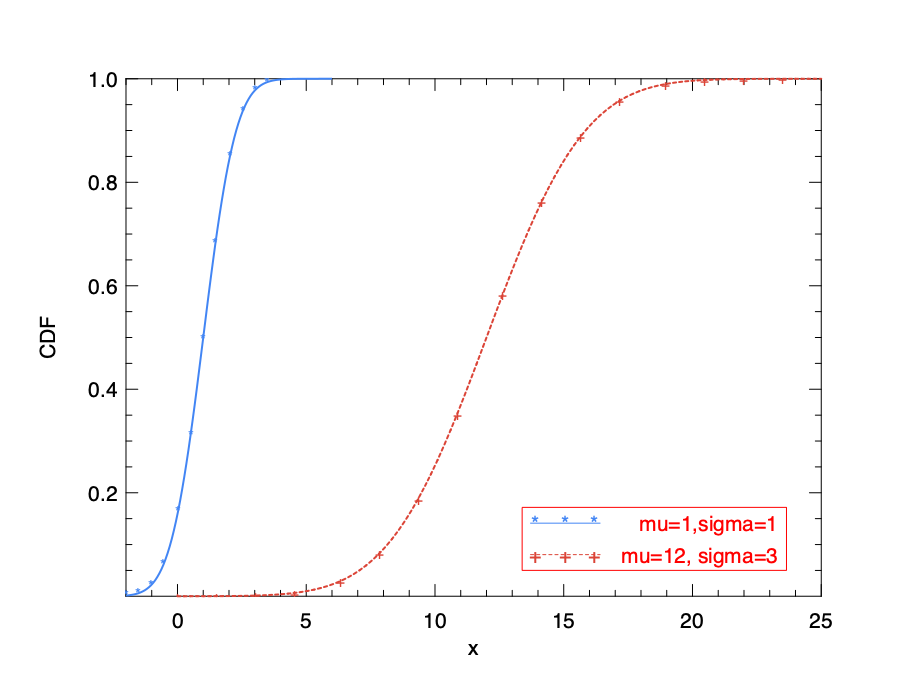

The CDF of Gaussian can be calculated with infinite summation, i.e. integration:

\[p(x\leq~k)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^k~e^{-t^2/2}dt.\]We can observe this function with gaussian_cdf.

let h = Plot.create "plot_gaussian_cdf.png" in

Plot.set_ylabel h "CDF";

Plot.plot_fun ~h ~spec:[ RGB (66,133,244); LineStyle 1; LineWidth 2.; Marker "*" ] (fun x -> Stats.gaussian_cdf ~mu:1. ~sigma:1. x) (-2.) 6.;

Plot.plot_fun ~h ~spec:[ RGB (219,68,55); LineStyle 2; LineWidth 2.; Marker "+" ] (fun x -> Stats.gaussian_cdf ~mu:12. ~sigma:3. x) 0. 25.;

Plot.(legend_on h ~position:SouthEast [|"mu=1,sigma=1"; "mu=12, sigma=3"|]);

Plot.output h

Descriptive Statistics

A random variables describes one individual event. A whole collection of individuals that of certain interests becomes a population. A population can be characterised with multiple descriptive statistics. Two of the most frequently used of them are mean and variance. The mean of a population \(X\) with \(n\) elements is defined as:

\(E(X) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i}x_i,\) where \(x_i\) is the \(i\)-th element in population. And the definition of variance is similar:

\[Var(X) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i}(x_i - E(X))^2.\]A similar and commonly used idea is standard deviation, which is the square root of variance. The meaning of both the mean (or expected value) and the variance are plain to see, the first being a representative central value of a population, and the second being how the values spread around the central expectation.

These definitions are for discrete random variables, but they can easily be extended to the continuous cases. To make it more general, we define the n-th moment of a real variable about a value X as:

\[M_n(X) = \int_x~(x_i - c)^2~f(x_i)dx,\]where \(f(x)\) is the the continuous function of the variable \(X\), and \(c\) is certain constant.

You can see that the mean value is actually the first order moment, and variance is the second order.

The third order moment is called skewness, indicating the asymmetry of the probability distribution of a real random variable.

The fourth order moment is called kurtosis, and it shows how long a “tail” the probability distribution has.

Let’s look at one simple example.

We first draw one hundred random numbers which are uniformly distributed between 0 and 10. Here we use Stats.uniform_rvs function to generate numbers following uniform distribution.

let data = Array.init 100 (fun _ -> Stats.uniform_rvs 0. 10.);;

Then We use mean function calculate sample average. As can be expected, it is around 5. We can also calculate other higher moments easily with corresponding functions.

We can do a very rough and quick interpretation about these results. It has a widely spread distribution (about 3 to the left and right), and the distribution is not skew, according to a very small skewness number. Finally, a small kurtosis shows that the distribution does not have an obvious tail.

# Stats.mean data

- : float = 5.18160409659184573

# Stats.std data

- : float = 2.92844832850280135

# Stats.var data

- : float = 8.57580961271085229

# Stats.skew data

- : float = -0.109699186612116223

# Stats.kurtosis data

- : float = 1.75165078829330856

The following code calculates different central moments of the distribution. A central moment is a moment of a probability distribution of a random variable about the random variable’s mean. The zero-th central moment is always 1, and the first is close to zero, and the second is close to the variance.

# Stats.central_moment 0 data

- : float = 1.

# Stats.central_moment 1 data

- : float = -3.13082892944294137e-15

# Stats.central_moment 2 data

- : float = 8.49005151658374224

# Stats.central_moment 3 data

- : float = -2.75496511397836663

Besides the moments, we also use order statistics frequently to understand data. Order statistics and rank statistics are among the most fundamental tools in non-parametric statistics and inference. The \(k^{th}\) order statistic of a statistical sample is equal to its k-th smallest value. The example functions of

There are many ordered statistical functions in the Stat module in Owl for you to explore.

Some of the most frequently used are shown as follows:

Stats.min;;

Stats.max;;

Stats.median;;

Stats.quantile;;

Stats.first_quartile;;

Stats.third_quartile;;

Stats.percentile;;

The min and max is plain to use.

The median is the middle number in a sorted list of numbers of the whole samples.

It is sometimes more descriptive than the mean about the data, since the later is more prone to outliers.

A similar idea is quartile: there are 75% of the measurements in the sample are larger than the first quartile, and 25% are larger than the third quartile.

The median is also the second quartile.

A more general idea is the percentile, a measure at which that percentage of the total values are below that measure.

For example, the first quartile is also the 25th percentile.

Special Distribution

All distributions are equal, but some are more equal than others. Certain types of special distributions are used again and again in practice and are given special names. A small number of them are listed in the table below.

| Distribution name | |

|---|---|

| Gaussian distribution | \(\frac{1}{\sigma {\sqrt {2\pi }}}e^{-{\frac {1}{2}}\left({\frac {x-\mu }{\sigma }}\right)^{2}}\) |

| Gamma distribution | \(\frac{1}{\Gamma(k)\theta^k}x^{k-1}e^{-x\theta^-{1}}\) |

| Beta distribution | \(\frac{\Gamma(\alpha + \beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha)\Gamma(\beta)}x^{\alpha-1}(1-x)^{\beta-1}\) |

| Cauchy distribution | \((\pi~\gamma~(1 + (\frac{x-x_0}{\gamma})^2))^{-1}\) |

| Student’s \(t\)-distribution | \(\frac{\Gamma((v+1)/2)}{\sqrt{v\pi}\Gamma(v/2)}(1 + \frac{x^2}{v})^{-\frac{v+1}{2}}\) |

Here \(\Gamma(x)\) is the Gamma function.

These different kinds of distributions are supported in the Stats module in Owl. For each distribution, there is a set of related functions using the distribution name as their common prefix.

For example, for the gaussian distribution, we can utilise the function below:

gaussian_rvs: random number generator.gaussian_pdf: probability density function.gaussian_cdf: cumulative distribution function.gaussian_ppf: percent point function (inverse of CDF).gaussian_sf: survival function (1 - CDF).gaussian_isf: inverse survival function (inverse of SF).gaussian_logpdf: logarithmic probability density function.gaussian_logcdf: logarithmic cumulative distribution function.gaussian_logsf: logarithmic survival function.

Stats module supports many distributions. For each distribution, there is a set of related functions using the distribution name as their common prefix.

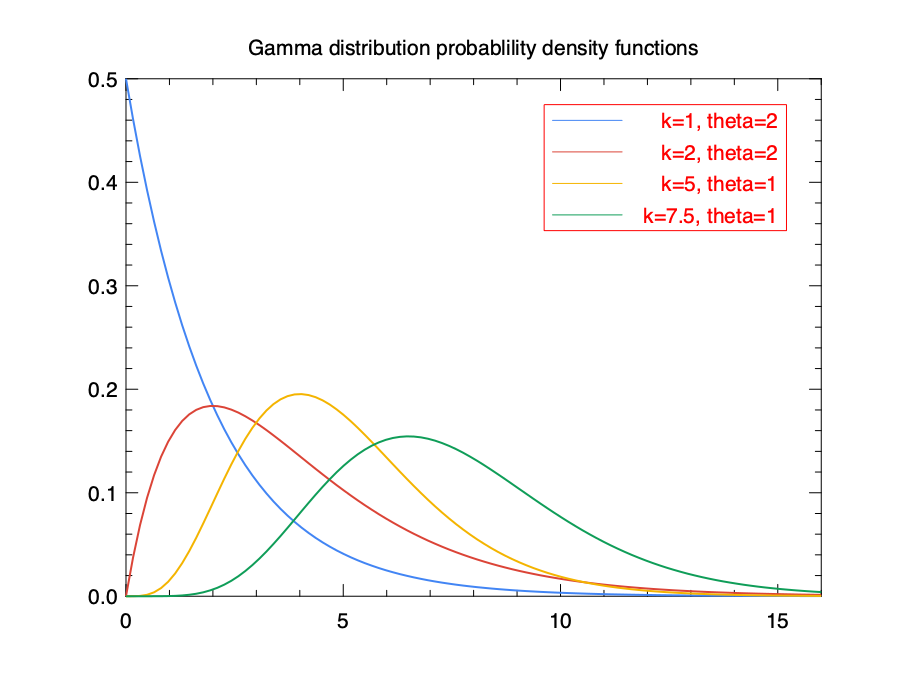

As an example, the code below plots the probability density function of the Gamma distribution using gamma_pdf.

The result is shown in the figure below.

module N = Dense.Ndarray.D

let _ =

let x = N.linspace 0. 16. 100 in

let f1 x = Owl_stats.gamma_pdf x ~shape:1. ~scale:2. in

let f2 x = Owl_stats.gamma_pdf x ~shape:2. ~scale:2. in

let f3 x = Owl_stats.gamma_pdf x ~shape:5. ~scale:1. in

let f4 x = Owl_stats.gamma_pdf x ~shape:7.5 ~scale:1. in

let y1 = N.map f1 x in

let y2 = N.map f2 x in

let y3 = N.map f3 x in

let y4 = N.map f4 x in

let h = Plot.create "gamma_pdf.png" in

let open Plot in

set_xlabel h "";

set_ylabel h "";

set_title h "Gamma distribution probablility density functions";

plot ~h ~spec:[ RGB (66, 133, 244); LineStyle 1; LineWidth 2. ] x y1;

plot ~h ~spec:[ RGB (219, 68, 55); LineStyle 1; LineWidth 2. ] x y2;

plot ~h ~spec:[ RGB (244, 180, 0); LineStyle 1; LineWidth 2. ] x y3;

plot ~h ~spec:[ RGB (15, 157, 88); LineStyle 1; LineWidth 2. ] x y4;

Plot.(legend_on h ~position:NorthEast [|"k=1, theta=2"; "k=2, theta=2"; "k=5, theta=1"; "k=7.5, theta=1"|]);

output h

Multiple Variables

So far we have talked about one single random variable, but a problem often involves multiple variables. For example, in a data centre, if we know the probability that the servers stop working, and the probability that the network links break, we might want to consider the probability that a data centre functions normally. The joint probability of two random variable \(X\) and \(Y\) is expressed as \(p(X, Y)\), or \(P(X~\cap~Y)\), indicating the probability of the two events happened at the same time.

There is one special case where the joint probability is intuitive to compute. If the two events are independent, i.e. not related with each other, then the probability of result \(X=x\) and \(Y=y\) is:

\[p(xy) = p(X=x \textrm{AND } Y=y) = p(X=x) * p(Y=y) = p_X(x)p_Y(y).\]Another related concept is the conditional probability. Intuitively, many events in the real world are not totally independent with each other. For example, consider the probability that a person put a raincoat, and the probability that a person put on a raincoat in a rainy day. The events “putting on raincoat” and “rainy day” are apparently related. Formally, the probability of event A given event B is computed as:

\[P(X | Y) = \frac{P(X~\cap~Y)}{P(Y)}.\]There is not doubt that the most important application of conditional probabilities is the Bayes’ Theorem, proposed first by Thomas Bayes in 1991. It is expressed by an simple form as shown in the equation, e.g. it provides a way to compute the condition probability when it is not directly available.

\(P(X\|Y) = \frac{P(Y\|X)P(X)}{P(Y)}\) {#eq:stats:bayes}

One powerful application of this theorem is that it provides the tool to calibrate your knowledge about something (“it has 10% percentage to happen”) based on observed evidence. For example, a novice hardly tell if a dice is normal or loaded. If I show you a dice and ask you to estimate the probability that this dice a fake one, you would say “hmm, I don’t know, perhaps 10%”. Define event \(X\) to be “the dice is loaded”, and you just set a prior that \(P(X) = 0.1\). Now I begin to roll for three times, and somehow, I got three 6’s. Now I ask you again, given the evidence you just observed, estimate again the probability that the dice is loaded. Define \(Y\) as the event “get all 6’s of all three rolling”.

We can easily calculate that in the normal case \(P(Y) = 1 / 6^3 \approx 0.005\), and the probability this “normal case” happens, is 90%, according to our prior knowledge.

In total, \(P(Y) = P(Y|X)P(X) + P(Y|X')P(X')\), where \(P(X')\) denotes the probability the dice is normal one.

Besides, we can say that getting all 6’s if the dice is loaded \(P(Y | X)\) would be pretty high, for example 0.99.

Therefore, we can calculate that, now that given the observed evidence, the dice is loaded with a probability

\(P(X|Y) = \frac{0.99 * 0.1}{0.99~\times~0.1 + 0.005~\times~0.9} \approx 0.96\).

This is the posterior that we get after observing the evidence, which improves our previous knowledge significantly.

This process can be widely applied to numerous scientific fields, where existing theory or knowledge are often put to test with new evidences.

Sampling

We have talked about using random variables to describe certain events of interests. The whole of individuals constitutes population. It can be characterised by statistics such as mean, standard deviation as we have shown before. However, in the real world, most population is difficult to enumerate, if not possible. For example, if we are interested to know the average weight of all sands on earth, then it surely difficult to measure them one by one. Instead, a sample is required to represent this population.

Unbiased Estimator

There can be multiple ways to do the sampling. Random sampling is a common choice. A similar method is “stratified random sampling”, which first divide population into several groups, and then choose randomly within each group. For example, in designing a questionnaire, you want people from all age groups to be equally represented, and then stratified randomly sampling would be a more proper method. Of course, more sampling methods are also plausible as long as the sample is representative, which means that a member in the population is equally possible to be chosen into the sample.

After choosing a suitable sample, the next thing is to describe the population with the sample. The statistics such as mean and variance etc. are still very useful, but can we directly use the statistics of the sample and declare that they can also be used to represent the whole population? In fact, that depends on if the statistics is an unbiased estimator, i.e. the expected value of its value is the corresponding population parameter.

For example, let’s take a sample of \(n\) elements, and its mean \(m\) is:

\[m = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n~x_i,\]where \(x_i\) is an element in the sample. Denoting the population as \(\mu\), it can be further proved that: \(E(m) = \mu\). Therefore, the sample mean is an unbiased estimator of the population.

The same cannot of said of variance. The sample variance is:

\[v = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i - m)^2.\]Assume the variance of population is \(\sigma^2\), then it can be proved that \(E(v) = \frac{n - 1}{n}\sigma^2\). Therefore, the unbiased estimator of population variance of not that of the sample \(v\), but \(\frac{n}{n-1}v\).

Inferring Population Parameters

In the previous section, we have shown how to get the expected value of the mean and variance of the population, given a sample from this population. But we perhaps need to know more than just the expected value. For example, can we locate an interval in which we can be quite sure the population mean lies? This section investigates this question.

First, we need to explain the Central Limit Theorem. It states that, if you have a population and take sufficiently large random samples from the population with replacement, the distribution of the sample means will be approximately normally distributed. If the sample size is sufficiently large (such as \(n \lt 20\)), this theorem holds true regardless of the population distribution.

Specifically, suppose we repeatedly sample a subset of the same size \(n\), and we can then define random variable \(X\) to represents the mean value of each sampled subset. According to the central limit theorem, it can be derived that, suppose the population has mean \(\mu\) and variance of \(\sigma^2\), both unknown, then \(X\) follows a normal distribution of mean value \(\mu\), and variance \(\frac{\sigma^2}{n}\).

Since both the mean and the variance of the population is unknown, apparently we cannot solve this case with mystery at both ends. To get a more precise estimation about population mean \(\mu\), let’s first assume that the population variance can be calculated directly with the sample variance: \(\sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i - m)^2\). This assumption is of good quality in practice when \(n\) is sufficiently large.

Now that we know \(X\) follows a normal distribution, we can utilise some of this nice properties. For example, we know that 95% of the probability mass lies within 1.96 standard deviations of this means. We can verify this point this simple code using the CDF function of normal distribution:

# let f = Stats.gaussian_cdf ~mu:0. ~sigma:1. in

f 1.96 -. f (-1.96)

- : float = 0.950004209703559

Therefore, for any value \(x\) in \(X\), we know that: \(P(\mu - 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \le x \le \mu + 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}).\)

With a bit variation, it becomes:

\[P( x - 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \le \mu \le x + 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}).\]That means that given the sample mean \(m\), the population mean \(\mu\) lies within this range [\(m - 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\), \(m + 1.96~\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)] with 95% probability. It is called its confidence interval. Again, the population variance \(\sigma^2\) directly use that of the unbiased estimation from sample.

Let’s go back to the 1.96 number. We use this range because X is assumed to follow a normal distribution. The \(\frac{x - \mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}\) variable follows a standard normal distribution. It is called tne standard Z variable. We can check the standard normal distribution table to find the range that corresponds to 95% confidence. However, as we have explained, this does not hold when \(n\) is small, since we actually uses \(\frac{x-\mu}{\sqrt{\frac{\sum_{i}(x - m)^2}{n(n-1)}}}\) instead of the real \(z\) variable. The latter one is called standard t variable, which follows the t-distribution with \(n-1\) degree of freedom. When \(n\) is a large number, the t distribution behave almost the same as that of a normal distribution. Therefore, if the \(n\) is small, we need to look up the t table. For example, if \(n=17\), then the range parameter is about 2.12, which can be verified as:

# let f x = Stats.t_cdf x ~df:16. ~loc:0. ~scale:1. in

f 2.12 -. f (-2.12)

- : float = 0.950009071286895823

That’s all for the population mean. The estimation of population variance range uses \(\chi\)-square distribution, but rarely used in practice. So we omitted it in this section.

Hypothesis Tests

Theory

While descriptive statistics solely concern properties of the observed data, statistical inference focusses on studying whether the data set is sampled from a larger population. In other words, statistical inference make propositions about a population. Hypothesis test is an important method in inferential statistical analysis.

Let’s think about the classic flip coin experiment. Suppose we have a basic assumption/hypothesis that most coins can give a result of head or tail with 50/50 chance. Now, if you flip a given coin 3 times and get 3 heads, can you make a claim that this coin is not a normal one? With how much probability? Another example is that, suppose you claim that one of your proposed algorithm improves the running speed of the state of art, and you have two samples about the execution time using two different algorithms, and then how can you be sure that your claim is justified. That’s where we need hypothesis tests.

There are two hypotheses proposed with regard to the statistical relationship between data sets.

- Null hypothesis \(H_0\): there is no relationship between two data sets.

- Alternative hypothesis \(H_1\): there is statistically significant relationship between two data sets.

The probability of an outcome assuming that a hypothesis is true is called its p-value. In practice the p-value is set to 5% (1% is also used frequently). For example, if we believe that a coin is a normal one, but the experiment result can only happen with a low probability of, e.g. 0.03 given this belief, we can reject the the hypothesis (“this coin is normal”), at the 5% confidence level.

Note that, if we do not reject a hypothesis, that does not mean it is accepted. If we flip the coin three times and get three heads. Given the hypothesis that this coin is normal, this result happens with a probability of 12.5%, therefore we cannot reject this hypothesis.

The non-rejection does not mean we are pretty sure the coin is totally not biased with much confidence.

Therefore, one needs to be very careful in choosing hypothesis.

\(H_0\) should be something we believe is solid enough to explain the data unless the strongly challenged by observed data.

Besides, it also helps to make the null hypothesis as precise as possible. A wide coverage only makes the hypothesis undeniable.

Gaussian Distribution in Hypothesis Testing

One of the most common test to make is to see if observed data come from a certain gaussian distribution.

This is called a “z-test.”

Now let’s see how to perform a z-test in Owl. We first generate two data sets, both are drawn from Gaussian distribution but with different parameterisation. The first one data_0 is drawn from \(\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\), while the second one data_1 is drawn from \(\mathcal{N}(3, 1)\).

let data_0 = Array.init 10 (fun _ -> Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:0. ~sigma:1.);;

let data_1 = Array.init 10 (fun _ -> Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:3. ~sigma:1.);;

Our hypothesis is that the data set is drawn from Gaussian distribution \(\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\). From the way we generated the synthetic data, it is obvious that data_0 will pass the test, but let’s see what Owl will test us using its Stats.z_test function.

# Stats.z_test ~mu:0. ~sigma:1. data_0

- : Owl_stats.hypothesis =

{Owl.Stats.reject = false; p_value = 0.289340080583773251;

score = -1.05957041132113083}

The returned result is a record with the following type definition. The fields are self-explained: reject field tells whether the null hypothesis is rejected, along with the p value and score calculated with the given data set.

type hypothesis = {

reject : bool;

p_value : float;

score : float;

}

From the previous result, we can see reject = false, indicating null hypothesis is rejected, therefore the data set data_0 is drawn from \(\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\). How about the second data set then?

# Stats.z_test ~mu:0. ~sigma:1. data_1

- : Owl_stats.hypothesis =

{Owl.Stats.reject = true; p_value = 5.06534675819424548e-23;

score = 9.88035435799393547}

As we expected, the null hypothesis is accepted with a very small p value. This indicates that data_1 is drawn from a different distribution rather than assumed \(\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\).

In the previous section we have introduced the z-variable and t-variable.

Besides the z-test, another frequently used test is to see if the given data follows a Student’s t-distribution under the null hypothesis.

In the Stats module, the t_test ~mu ~alpha ~side x function returns a test decision of t-test, which is a parametric test of the location parameter when the population standard deviation is unknown. Here mu is population mean, and alpha is the significance level.

Two-Sample Inferences

Another common type of test is to test if two samples comes from the same population. For example, we need to test performance of the improvement to an algorithm to see if it really works. The default null hypothesis is that, the two samples are drawn from the same population. The test strategy depends on if the sample sizes.

If the two samples are of the same size, then the test can be simplified by subtracting the elements in the two sets one-by-one.

The test then becomes to check if the resulting set is taken from a population of mean value 0.

This problem can be solved with the method introduced in the previous section by using t-test.

Specifically, we provides the paired sample t-test function.

The t_test_paired ~alpha ~side x y returns a test decision for the null

hypothesis that the data in x – y comes from a normal distribution with

mean equal to zero and unknown variance.

The problem get trickier when the size of these two subsets are not the same. We then need to discuss the two cases about their confidence interval. If both intervals do not overlap, apparently we can be fairly certain that the two samples come from different population, and thus reject the null hypothesis. If the intervals overlap, we need to make sure that some other conditions stand. For example, if we can assume that the variances of both population are the same, then it can be shown that the variable:

\[\frac{\bar{x} - \bar{y}}{\sqrt{\frac{\sum_{i=1}^a~(x_i - \bar{x})^2 + \sum_{i=1}^b~(y_i - \bar{y})^2}{a + b - 2}(\frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{b})}},\]is a standard t variable with \(a + b - 2\) degree of freedom, where \(a\) and \(b\) are the length of the sample \(X\) and \(Y\).

This idea is implemented as the unpaired sample t-test.

The function t_test_unpaired ~alpha ~side ~equal_var x y returns a test decision for

the null hypothesis that the data in vectors x and y comes from

independent random samples from normal distributions with equal means and

equal but unknown variances.

Here equal_var indicates whether two samples have the same variance.

If the two variances are not the same, we need to use the nonparametric tests such as Welche’s t-test.

Other Types of Test

Besides what we have mentioned so far, the Stats module in Owl supports many other different kinds of hypothesis tests.

This section will give them a brief introduction.

-

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test:

ks_test ~alpha x freturns a test decision for the null hypothesis that the data in vectorxcomes from independent random samples of the distribution with CDF f. The alternative hypothesis is that the data inxcomes from a different distribution. The result(h,p,d):dis the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistic. -

Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test:

ks2_test ~alpha x yreturns a test decision for the null hypothesis that the data in vectorsxandycome from independent random samples of the same distribution. -

Chi-Square Variance Test

var_test ~alpha ~side ~variance xreturns a test decision for the null hypothesis that the data inxcomes from a normal distribution with inputvariance, using the chi-square variance test. The alternative hypothesis is thatxcomes from a normal distribution with a different variance. -

Jarque-Bera Test

jb_test ~alpha xreturns a test decision for the null hypothesis that the dataxcomes from a normal distribution with an unknown mean and variance, using the Jarque-Bera test. -

Wald–Wolfowitz Runs Test

runs_test ~alpha ~v xreturns a test decision for the null hypothesis that the dataxcomes in random order, against the alternative that they do not, by running Wald–Wolfowitz runs test. The test is based on the number of runs of consecutive values above or below the mean ofx.~vis the reference value, the default value is the median ofx. -

Mann-Whitney Rank Test

mannwhitneyu ~alpha ~side x yComputes the Mann-Whitney rank test on samples x and y. If length of each sample less than 10 and no ties, then using exact test, otherwise using asymptotic normal distribution.

Covariance and Correlations

Correlation studies how strongly two variables are related. There are different ways of calculating correlation. For the first example, let’s look at Pearson correlation.

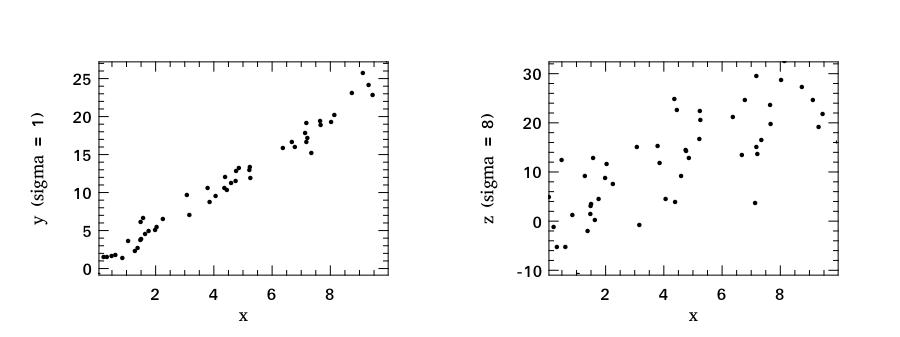

x is our explanatory variable and we draw 50 random values uniformly from an interval between 0 and 10. Both y and z are response variables with a linear relation to x. The only difference is that we add different level of noise to the response variables. The noise values are generated from Gaussian distribution.

let noise sigma = Stats.gaussian_rvs ~mu:0. ~sigma;;

let x = Array.init 50 (fun _ -> Stats.uniform_rvs 0. 10.);;

let y = Array.map (fun a -> 2.5 *. a +. noise 1.) x;;

let z = Array.map (fun a -> 2.5 *. a +. noise 8.) x;;

It is easier to see the relation between two variables from a figure. Herein we use Owl’s Plplot module to make two scatter plots.

(* convert arrays to matrices *)

let x' = Mat.of_array x 1 50;;

let y' = Mat.of_array y 1 50;;

let z' = Mat.of_array z 1 50;;

(* plot the figures *)

let h = Plot.create ~m:1 ~n:2 "plot_01.png" in

Plot.subplot h 0 0;

Plot.set_xlabel h "x";

Plot.set_ylabel h "y (sigma = 1)";

Plot.scatter ~h x' y';

Plot.subplot h 0 1;

Plot.set_xlabel h "x";

Plot.set_ylabel h "z (sigma = 8)";

Plot.scatter ~h x' z';

Plot.output h;;

The subfigure 1 shows the functional relation between x and y whilst the subfiture 2 shows the relation between x and z. Because we have added higher-level noise to z, the points in the second figure are more diffused.

Intuitively, we can easily see there is stronger relation between x and y from the figures. But how about numerically? In many cases, numbers are preferred because they are easier to compare with by a computer. The following snippet calculates the Pearson correlation between x and y, as well as the correlation between x and z. As we see, the smaller correlation value indicates weaker linear relation between x and z comparing to that between x and y.

# Stats.corrcoef x y

- : float = 0.991145445979576656

# Stats.corrcoef x z

- : float = 0.692163016204755288

Summary

In this chapter, we briefly introduced several of the main topics in probability and statistics. Random variables and different types of distribution are two building blocks in this chapter. Based on them, we introduced the joint- and conditional probabilities when there are multiple variables. One important topic here is the Bayes Theorem. Then we went from descriptive statistics to inference statistics, and introduced sampling, including the idea of unbiased population estimator based on a given sample, and how to infer population parameters such as mean. Next, we covered the basic idea in hypothesis testing with examples. The difference between covariance and correlations is also discussed.